Louise Bourgeois, the French-American artist, a towering figure of Western contemporary art, had once famously declared: “A work of art doesn’t have to be explained. If you do not have any feeling about this, I cannot explain it to you. If this doesn’t touch you, I have failed.”

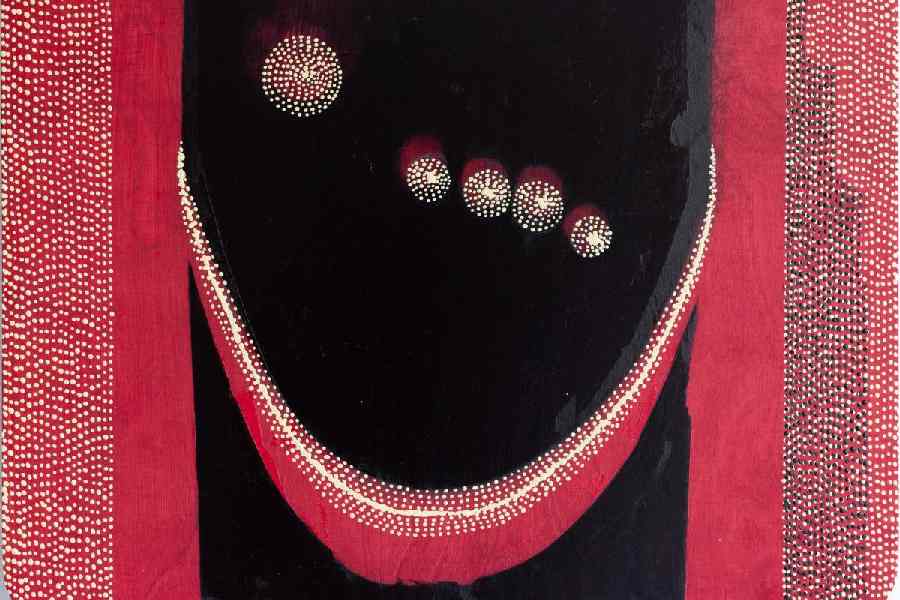

This is what came to mind for Radhika Khimji’s exhibition, The Line is Time, on view at Experimenter, Hindustan Road till January 3. Lozenges and triangles and other geometric forms in rich earth colours and charcoal grey, more often than not decked out with innumerable dots, appear in her works. The geometric forms occasionally lean against each other. Many of these are caught in a web of delicate lines surging across them, reminiscent of the fragile tracery of marks left behind momentarily on a sandy beach after a wave has receded. Some look like fossilised forms. Pale shadows of photographs of harsh and hilly terrain appear on the backdrop of some works. The geometric shapes seem to be floating in space.

Khimji, born in 1979, lives in and works from Muscat, Oman and London. She studied art at Slade at the University College London. She has learnt icon painting too. So geographical and cultural barriers mean nothing to her. The internet has smashed those encumbrances anyway. And imagination knows no bounds.

When one views her artwork, one could wonder, is Khimji alluding to Australian aboriginal art connected to the Dreaming? Or is it the richness of Nigerian art that she is referring to? It could also be the lacy dot patterns created by young people of Ethiopia, the tradition of tattoos and scarification being prevalent among the people of various regions of Africa. It could also be the bindu, the simple dot that plays a pivotal role in the world of Indian contemporary art today.

The press release is puzzling: “… She approaches time as a subjective experience, measured by our internal time-consciousness… Her works fundamentally challenge the perception of time and respond to interior circadian rhythms.” How does one relate this statement to the works on view, particularly the references to time? Such obfuscation is not unique. It has occasionally become difficult to find the connection between an artist’s statement and the works on view. Perhaps the knowledge of prosaic facts could help, as they do in Khimji’s case.

The Hajar mountains of Oman, of which Muscat is the capital, are a “geological wonder” with their varying timescales. Khimji belongs to a family that made Oman its home 150 years ago. Time varies for the artist herself in accordance with her geographical position. It keeps shifting from time to time.

Her family being worshippers of Shrinathji of Nathdwara by tradition, the lozenge shape alludes to the cut of the diamonds in the deity’s necklace that glows like the Milky Way around his throat. The parure is changed at various hours of the day and so are the matching costumes. This is the complex web of thoughts that is activated by Khimji’s works. Indeed, she does not present them literally — she simplifies them to such an extent that only traces remain. If one is aware, one looks for and locates these allusions.