Richard Holkar created the Sacred River Festival 22 years ago. This was shortly after he had opened his family home, Ahilya Fort, painstakingly renovated to be a serene, understated hide-out mingling guest rooms, courtyards, terraces and gardens. A highlight since my first stay is still the morning stroll from my room past ancient stone statues of Hanuman and Shiva, across a quiet courtyard, past priests chanting in tiny family temples as they make fresh lingams from the sacred Narmada’s mud, to the tree-shaded top terrace with views over the broad, slow-flowing river. Richard is usually already there, hosting with charm, wit and sharp-eyed precision. The breakfast table shows off the fort’s own honey, fresh fruits of perfect ripeness, and bread baked to recipes from Ireland’s top cookery school, Ballymaloe.

This, then, is the setting for his festival held in February. Three full days run seamlessly from breakfast into a two-hour lecture-demonstration by that evening’s performers, then to lunch-siesta-tea, with optional boat rides and visits to Rehwa Society to see traditional Maheshwar weaving which Richard and his wife Sally (now of WomenWeave) revived in 1978 – and, of course, some retail therapy. Then, the day’s climax: the performers’ concerts at sunset and after nightfall, with hot kachoris and terracotta cups of chai as interval energisers. Dinner and good chat follow while guests tuck into their thalis, whose katoris often contain the Fort’s own organic vegetables prepared to recipes from Richard and Sally’s 1975 book, Cooking of the Maharajas, which saved for posterity recipes from pre-Independent India’s great royal cooks.

The temples and Narmada River setting

The theme for this year’s festival was ‘Lost and found, the ebb and flow of tradition’. It looked at the changes and adaption that a wide range of performers have undergone through their own evolution as well as through threats from society’s changes and fashions, with particular focus on the surrounding state, Madhya Pradesh.

Under the knowledgeable and fluent guidance of Anjana Rajan as compere, performers gave insights into their techniques and interpretations. Jitender Singh Jamwal, born in Jammu into the Dogra community, has weathered his region’s upheavals to become a fine exponent of classical khayal vocal music, especially the ghazal. He talked about the listener’s need to ‘understand the poetry and appreciate the alliteration, rhyming, rhythm, wit and punning’.

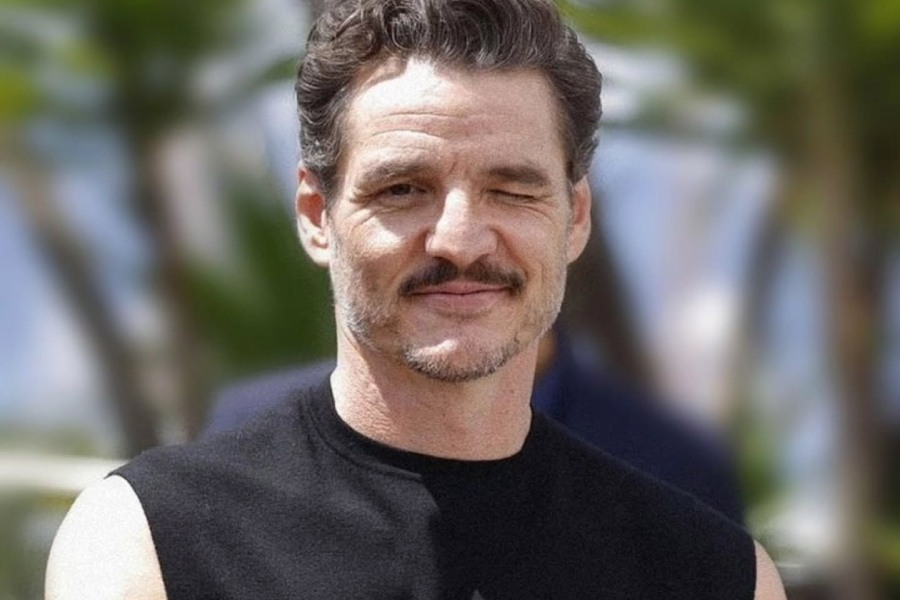

Jitender Singh Jamwal in concert

Taking Amir Khusrau’s poems about daily life, he helpfully translated into English some he would be singing that evening, and explained their deeper meanings. Then, discussing ragas, he insisted that in ghazals ‘everything is raga based’ and that ‘poetry has to be on top and not overwhelmed by music, even if simplified for a broader audience today’. As for the controversial question of amplification – which entirely changes how the music reaches the ear of the listener, reducing the rapport between performer and audience – he rightly bemoaned that a singer ‘no longer sings from deep in the diaphragm’. Our hopes rose that we might experience this in the evening, but sadly, the microphones won out.

A deep discussion of kathak dance followed, preparing us for that evening’s riverside performance by disciples of Guru Jyotsna Sohoni who founded the Bharatiya Nritya Kala Kendra in Indore 37 years ago. Text references of 1st century BC-2nd century AD refer to tying 200 bells on the dancer’s ankles to associate the joy of dance with the joy of temple bells. It’s all about control: today’s sophisticated dancer can perform while keeping her bells silent or, even more tricky, describe sounds with footwork such a drop of rain developing into a shower.

A kathak performance by the riverside

On other mornings, singer Kaluram Bamani talked about Kabir’s life as a weaver and how the rhythm of weaving is in his poetry, citing images of the fine cloth of life we are given at birth which is easily blemished and stained, so we must live life carefully. Born into a farming community in Dewas in the ancient Malwa region, Bamani’s epithet is ‘Kabir of Malwa’. The remarkable Maihar Band, founded in 1907 by Maihar’s court musician Allauddin Khan (guru to Ravi Shankar and others), was originally composed of orphans. Considered India’s first classical music band, today their future is unfunded and uncertain but they gave a rousing demonstration of Khan’s song inspired by Bengali baul singers.

Singer Kaluram Bamani and accompanying musicians perform under a banyan tree

In contrast, Balkrishna Masage demonstrated Kalsutri Behulua (‘puppet strings’), the marionettes found in Pinguli on coastal Maharashtra, using brightly painted puppets that he and his Adivasi troupe make themselves; they also write the stories and songs, perform each part, and make the scenery. As wandering entertainers, he said, ‘Shivaji used us as undercover spies, reporting directly to him’; but today, with TV for entertainment and a social stigma for the puppeteer, they perform stories about social issues as much as episodes from the Ramayana.

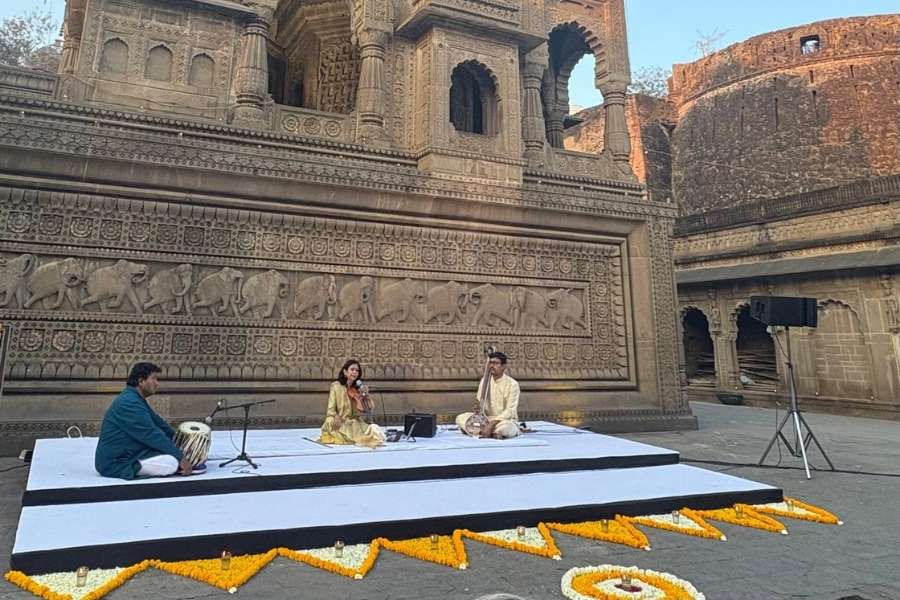

Ahilya Fort’s location on a bluff above some of the devout Rani Ahilyabai’s temples, spreading ancient banyan trees, and the wide ghats provided a string of sublime theatrical setting for the concerts. Anupriya Deotale gave the final one on her violin, sat before a temple’s elephant frieze as sunset ripened. In the morning, she had talked about the violin becoming part of Karnatic music, its distinctly Indian sliding technique, its entering into Madhya Pradesh music. She also talked about her guru, sarod player Amjad Ali Khjan – ‘I went to be his disciple, he was my guru, basically I play from sarod, sarangi and vocal, I’ve never learnt Hindustani violin!’. And yet, she says, ‘I’m born to play this instrument’.

Anupriya Deotale’s performance in front of a temple’s elephant frieze

Coming from Indore, Deotale said, “It was my dream to play here at Maheshwar, a raga.” And she did. Then she announced: “All that I play is improvised, violin is an international instrument”, and gave us a taste of the fusion music she plays with her band in Austria, Parinday – Music of the Soul. Performance moving from tradition to today.

Richard’s format is simple but rigorous: a well-honed structure, top-quality compere, performers who are also articulate, his renowned good food, and – to be frank – a carefully monitored guest list from across India and abroad to ensure all take full part. And they do, enthralled as much by the morning learning as the evening performances. Unlike some other festivals in India, Sacred River Festival remains true to its original aim. There has been no dumbing down. Long may it last!