Earlier this year, the four-year-old West Bengal Dalit Sahitya Academy hosted its first exhibition in Calcutta. It was titled Mahapran Jogendranath Mandal: Aandhar Raater Tara. The second part of the title, which is in Bengali, roughly translates thus, star of the dark night.

When The Telegraph asked Bengalis across different age groups in Calcutta if they knew of Jogen Mandal, the standard response was something between a shrug and a question — “The artist?”

Now, Jogen Chaudhuri is a famed artist. The confusion has nothing to do with him. It only bears up the fact that several generations of Bengalis haven’t heard of the other Jogen.

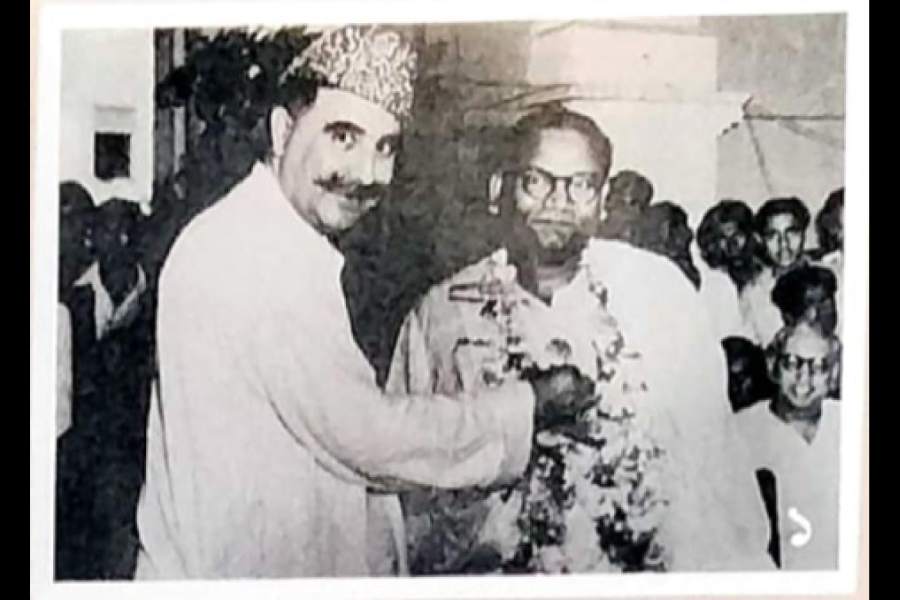

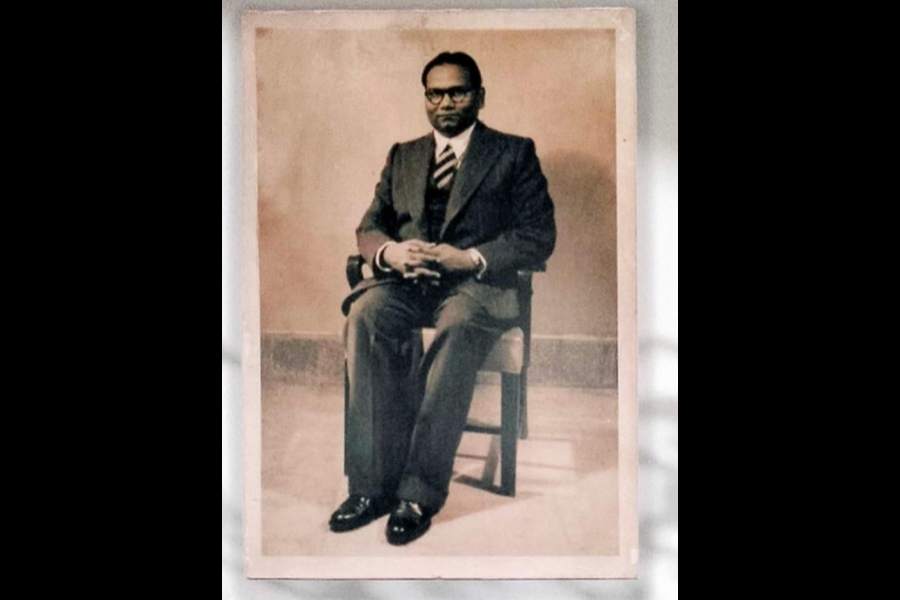

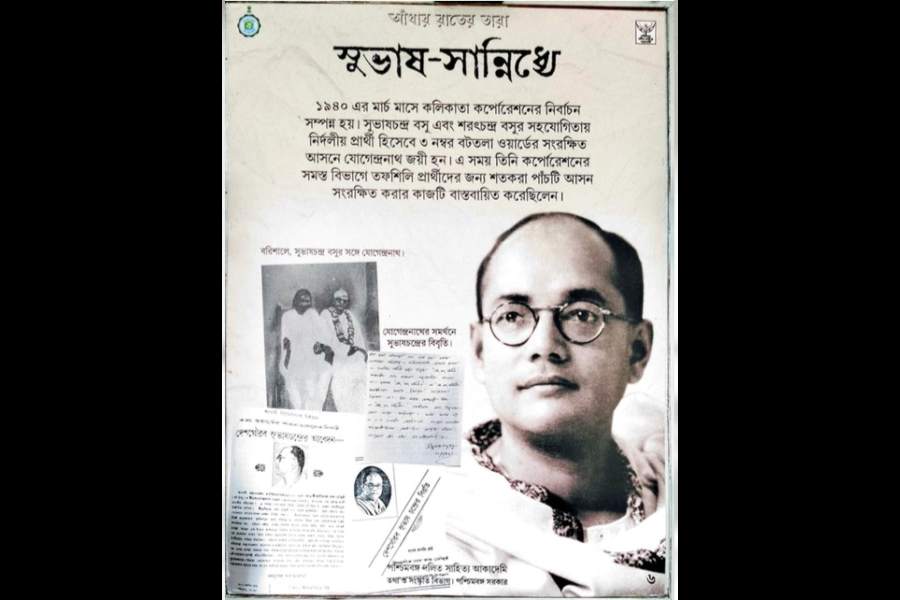

Jogendranath Mandal, a politician from the Namasudra community and head of the All India Scheduled Castes Federation in eastern India, who was responsible for Babasaheb Ambedkar’s election to the Constituent Assembly from Bengal in 1946. Courtesy: West Bengal Dalit Sahitya Academy

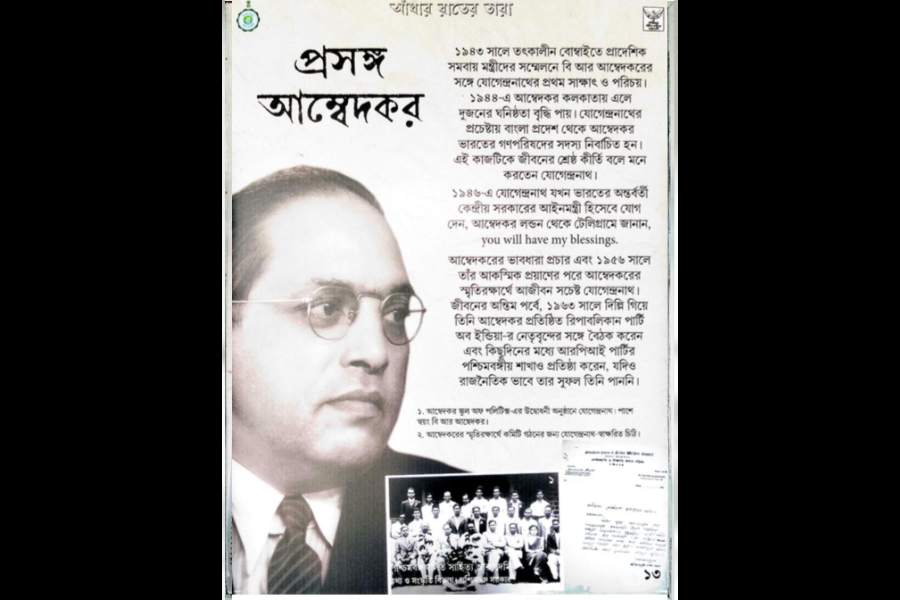

And yet, this was the man, the Bengali politician from the Namasudra community and boss of the All India Scheduled Castes Federation in eastern India, who was responsible for Babasaheb Ambedkar’s election to the Constituent Assembly of India from Bengal in 1946. At the time, Ambedkar did not have enough support in his home constituency Bombay Presidency. Mandal also served as law minister in the Interim Government of India, which functioned from 1946 until the transfer of power. And in 1947, when Ambedkar became the first law minister of independent India, Mandal took oath of office as the first law and labour minister in Jinnah’s Pakistan.

The exhibition at Rabindra Sadan was an effort to familiarise people with Mandal’s life and work through a series of photographs and accompanying legends. But this piece is an exploration of the forgetting of Jogen Mandal, not an exercise to profile him.

Of those that The Telegraph interviewed for this story, most said they had heard of Mandal while pursuing higher studies. Dwaipayan Sen, whose 2018 book is an authoritative text on Mandal in English from recent times, says he first “encountered” Mandal in graduate school at The University of Chicago, US.

Journalist and writer Ajoy Bose, who has written the political biography of Mayawati, says he first heard of Mandal in connection with Ambedkar.

“There are many reasons for not knowing Mandal,” says Sasti Sardar Bhoumik, who runs an NGO in Jharkhand. Among other things, she travels all over India conducting quizzes for schoolchildren on men and women from the Scheduled Caste community.

She continues, “The reasons for not knowing Mandal are political, societal, economic, cultural… We have grown up with a prescribed syllabus. The struggles of the people of the Bahujan community have never entered that syllabus. And how many of us read

beyond the syllabus? Jogen Mandal is out of syllabus.”

Poet and essayist Manohar Mouli Biswas is one of those few people remaining who has seen Mandal. The elder’s voice quivers with emotion when he speaks about “Jogenbabu”. He talks of Mandal as a kind of child prodigy, a heroic figure with god-given oratorial powers and organisational skills. Biswas says, “Jogenbabu came up from a place in society from where it is difficult to make such a steep climb.”

Mandal was from a peasant family. “He believed that in a predominantly agrarian nation, farmers should have more say in the democratic process,” says Biswas.

Two major constituents of undivided Bengal’s farming community were the Namasudras and the Muslims. Mandal tried to bring these two communities into mainstream politics and by causality into mainstream democratic processes, writes Sen in his book.

To do so, he aligned himself with the Muslim League. Mandal wrote: “principal objectives that prompted me… was, first that the economic interests of the Muslims in Bengal were generally identical with those of the Scheduled Castes. ...and secondly that the Scheduled Castes and the Muslims were both educationally backward”.

Nearly three decades after Mandal’s death in 1968, when sociologist Beth Roy conducted a series of interviews in Bangladesh for a project that explored social conflict, a middle-aged Namasudra farmer told her: “The caste Hindus left this land for India at the beginning. But our middle-class people and peasants didn’t want to go… Our Jogen Mandal made an alliance with Jinnah. Many of us believed then, ‘Let the caste Hindus go, but those of us who are peasants, whether Hindus or Muslims, can live together as brothers.”’

But that did not happen. And two years after Jinnah’s death, Mandal resigned from Liaquat Ali Khan’s Cabinet and left Pakistan. Upon his return to India, Mandal continued to be active in the political arena, continued to fight for the Dalit cause, but couldn’t cobble any sustainable tie with either the Congress or the Left parties.

And today the BJP might cry caste census but when the 1941 Census showed a decrease in the number of Dalits in Bengal, many said, Mandal included, that the Hindu Mahasabha manipulated the count to inflate the number of Hindus.

For the same reasons that Biswas and like-minded others extol Mandal, Bengal’s Hindu upper-caste citizenry turned against him.

“They said he partitioned Bengal, sided with the Muslims, they called him Jogen Ali Mollah,” says Biswas. In this innings, Mandal failed miserably at electoral politics. In his final years, Mandal lived atop a furniture shop in south Calcutta.

Remembering and forgetting are not absolutes. Chapters and characters from history play hide and seek with time and context.

Biswas talks about how Kanshi Ram spent months in Bengal when he was still working on the blueprint of the Bahujan Samaj Party. “He believed that West Bengal could be the karmasthal of Dalit politics given the land and its people’s connection with Mandal.” Ajoy Bose remembers discussing Mandal with Kanshi Ram in the 1980s. He tells The Telegraph that Kanshi Ram “abandoned Bengal” when he realised that Dalit politics in the state was very weak.

Many of the interviewees said there has been a rekindling of interest in Mandal the last five years. PM Modi invoked Mandal in 2020 while talking about the repression of minorities in Pakistan. In 2023, the Mamata Banerjee government set up the Dalit Bandhu Welfare and Development Board.

Others said it has been happening since the onset of the new millennium. In 2010, Debes Ray’s novel Barishaler Jogen Mandal made ripples. Bose points out that in the 2017 Uttar Pradesh elections when Mayawati tried to hard-sell a Dalit-Muslim alliance, Mandal was invoked.

Bengali writer-activist Kapil Krishna Thakur points out that in post-Hasina Bangladesh, where minorities are under attack, there is an effort by a section of the intelligentsia to resurrect Mandal’s political vision.

More than one person seemed taken with the dark night-lone star imagery. And while you may debate that one, it is a good excuse to share this anecdote by Thakur. Year: 1967. Mandal was getting ready to contest elections on the Republican Party of India ticket from Bongaon.

As Thakur recalls, “He was to address a public meeting near Habra, but he didn’t get there till late evening. Some seven or eight of us gathered on an empty field. The grass was wet from all that dew and cold, so we kept standing. I was in Class VIII. I had no idea of politics or political oratory. But when he started to speak, I listened engrossed. After a while, I realised that the field was all lit up. I looked around and it was full of people, villagers with hurricane lanterns in hand, vendors returning from the local haat with carbide lights at the end of a long stick...” Mandal died the next year.

In an email to The Telegraph, Sen says, “Mandal’s vision for Bengali society and politics (by the end of his life) amounted to a species of Ambedkarite socialism. This ideology and practice were deemed much too radical for the socially conservative mainstream.” He continues, “If he’s been forgotten, that forgetting has been, and remains, quite deliberate.”