The play Marx in Kolkata has had three shows so far. It is an adaptation of Marx in Soho by American historian Howard Zinn.

In the foreword to the original, Zinn writes that it was a “kind of fantasy”. Marx would return to a different time and geography, and “reminisce about his life in nineteenth century Europe”. Zinn’s Marx lands in Soho in 1990s New York instead of London, where he actually died in penury. In Koushik Sen’s play, Marx returns to Calcutta of the 21st century.

The play, directed and adapted by Sen and produced by the theatre group Swapnasandhani, is primarily in English with smatterings of Bengali and Hindi. It analyses the relevance of Marx in an erstwhile Marxist stronghold.

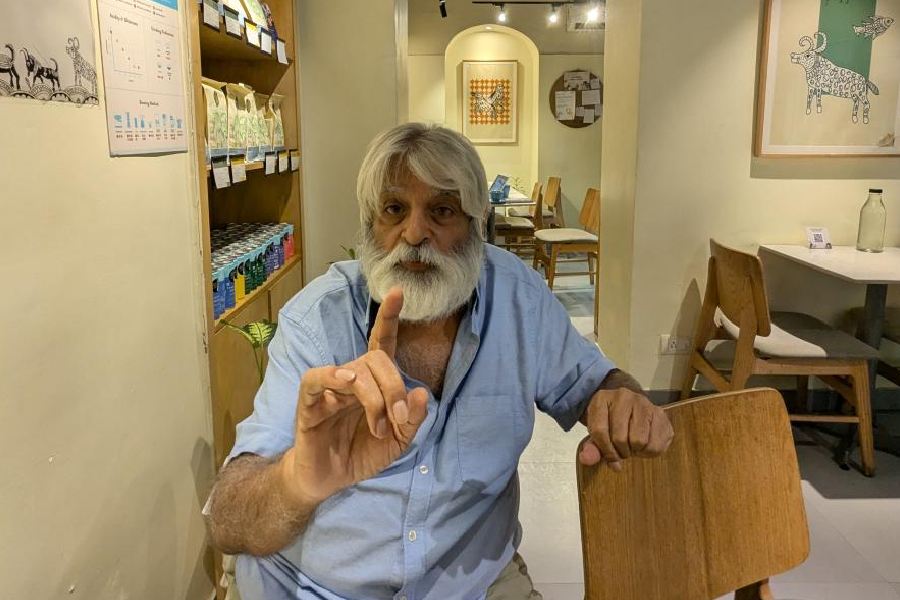

Before I actually come face to face with Jayant Kripalani that day in a coffee shop, I catch a glimpse of him through the shop window. The handsome face, so familiar from the iconic bhediye-ne-memne-ko-kaha cough drop ad from the 1980s, is covered with a flowing beard and hair worn long. To look the part, I presume.

“Those ads helped me pay my house rent and later settle down in Bombay,” says Kripalani. As he elaborates, it was those commercials that found him offers and work in teleserials, films…

But before all else, Kripalani fell in love with the stage. That was in 1967 and he had just seen Tom Stoppard’s absurdist play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead at London’s West End. Kripalani was in London to be trained in becoming an insurance underwriter.

Stoppard’s play expands on the exploits of two minor characters from Shakespeare’s Hamlet, the courtiers Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. “This magnificent play changed my world view,” says Kripalani. Soon after, utterly bored, he quit his training, returned to Calcutta and joined Jadavpur University, where he studied English literature.

It was while studying at Jadavpur that he made his stage debut as Hamlet for the theatre group Red Curtain. Later, he joined Shyamananda Jalan’s Padatik. His work there helped him bag a role in Shyam Benegal’s Arohan (1981).

Kripalani is a Calcuttan; he shifted to Bombay when he started his career as an advertising professional. “I realised soon enough that I couldn’t make a living out of acting alone,” he tells me. We are meeting in south Calcutta that day, but he had grown up in central Calcutta in the 1950s, the youngest son of a Sindhi family of eight in a house on Kyd Street.

His father Pritamdas, an emigre from Karachi, owned the shop Lindsay Dyeing and Dry Cleaning Company, which stood at the corner of Chowringhee Road and Lindsay Street. Kripalani says, “I grew up watching horse-drawn carriages pull up in front of New Market. The horses would stop to drink water from huge tubs.” He quips, “Our old rented house is now a seedy hotel. Dushtumir jaega.”

Because of his sociable parents, he and his five siblings knew all the families who ran shops in New Market. The children of shop owners were known as “market-er baccha”. Kripalani adds, “We played cricket at the Maidan and marble on the streets with all kinds of children. There was no class barrier.” But he does remember the odd cultural identifier “obangali” that was in use then as it is now.

Many of Kripalani’s memories of childhood and youth have found place in his short story collection New Market Tales and its sequel Cantilevered Tales.

In what he describes as his “post-retirement period”, Kripalani is well-engaged. He is a bitter critic of the current political system and often makes scathing attacks through social media posts, satirical poems and poetry reading sessions. He has spoken up against rape culture, corruption and identity/communal politics.

Along with his wife Gulan, he did a reading of a children’s book on India’s constitution by Justice Leila Seth; it was recorded for social media. “We want children to know about the Constitution’s principles and be inspired to live by them.” He’s even composed a baul song in English against the use and misuse of the Aadhar card after his sojourn at the minstrels’ akharas in Nadia. He has written the lines: “I’m a baul singer and I know I’m free/ I don’t need an Aadhar card to tell me I am ME.”

Kripalani takes pride in the fact that he’s been raised an atheist, in a cosmopolitan Calcutta. “I feel like vomiting when I think about today’s politics. I didn’t grow up in an India like this,” he says with disgust.

By his own admission, he did not know too much about Marx till this play happened. Kripalani’s Marx is brooding and perplexed. The actor tells me, “Initially, Koushik wanted the play to be in Hindi, but I told him I am not that confident in the language.” He is all praise for Sen, “full of ideas and surprises”, and open to “suggestions and changes in the script”. He expresses surprise that before Marx in Kolkata,

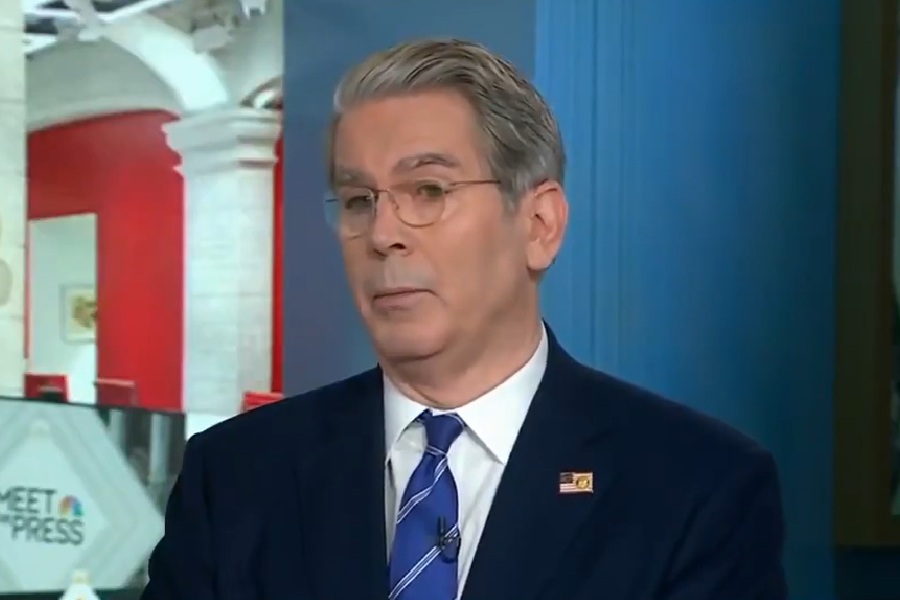

no one thought of utilising the fascinating technology — the revolving stage and the entrance from beneath — of GD Birla Sabhaghar. He loved working with film director Srijit Mukherji, who plays Mephistopheles, as well as the ensemble cast of young artistes.

As we wrap up, Kripalani tells me he is going to be on a two-month hiatus till the next show. What will he be doing till then? He replies, “I have promised myself that I will get back to finishing two half-baked books. But first, I shall get a shave and a haircut.”