The 48th edition of the Calcutta book fair ended in early February. What started as a humble affair at the Maidan in 1976 with a handful of publishers is now a 14-day event with 1,000 plus stalls and frills aplenty — panel discussions, book readings, cultural dos, themes, foreign invitees, selfie corners... The broad genres of writing remain the same, but newer themes jostle for attention.

One such theme that was quite apparent in this edition of the fair is the exploration of Muslim identity. Books written in Bengali with titles such as Islamophobia, Banglar Musalmaner Shikor O Atmaparichay, Bharatiyo Musalmaner Mon and Bangla Sahitye Musalman from a variety of publishers, old and new.

Not all the titles are quite as forthright. Rnaridighir Brittanto is a novel based on the Faraizi movement of the mid-19th century. Ismail Darbesh, 45, who has written the book, says, “The Faraizi movement had begun as a religious reformist movement

by Muslim purists. But with time, it changed character and assumed the shape of a farmers’ protest against greedy zamindars and talukdars.” The protagonist of

his novel is Mehrjaan, the daughter of a kaviraj who is hanged by the British. The novel itself is about her fight against the British administration as well as the

selfish zamindar.

'Ismail Darbesh' book cover

Darbesh says he wanted to portray the disunity among Muslims of Bengal. According to him, this is one of the reasons why the Faraizi Movement was short-lived. “The same is the story now,” he tells The Telegraph. “The book explores the relation between the abuser and the abused, the exploiter and the exploited, the tormentor and tormented.”

Srestho Galpo is a collection of short stories by Murshid A.M. The one titled Collateral Damage is the story of Payel and Absar, who run away and get married only to be hunted down by their disapproving families. The other stories in the collection — Sharbater Dokan, Gondi, Hatyar Samay Bodle Jai, Phool Kothay Rakhi — are about communal harmony, community clashes, about what turns someone into a fundamentalist. Kyiv Athoba Qayamatnagar is set against the backdrop of the

Russia-Ukraine war. The protagonist Yusuf is a medical student who has just returned from Kyiv and is making connections with what is happening in India.

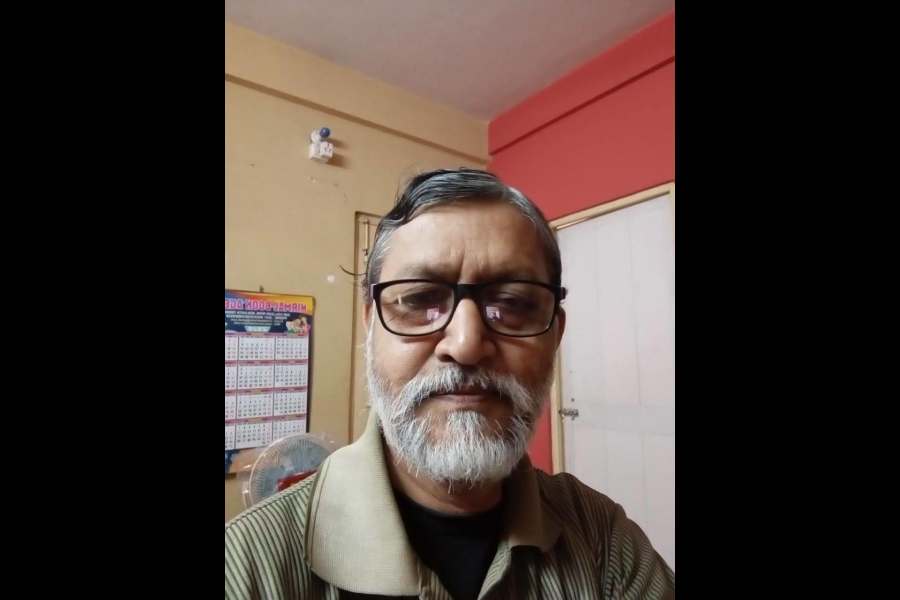

Murshid, 68, is a bookstore owner in south Calcutta’s Bansdroni, while Darbesh is a “tailor master” in Domjur in Howrah. Darbesh’s father specialised in zari work. Murshid’s father was a headmaster in a school. He says, “Our family was ousted from Calcutta during the 1964 riots. I grew up in a village near Bishnupur in South 24-Parganas.”

Aminul Islam’s Bangla Sahitye Muslim Ouponashik is a chronicle of Muslim novelists, men and women, who were active between 1857 and 2000 and their works. These include Mir Mosharraf Hossain, Qazi Imdadul Haq, Mohammad Najibar Rahman, Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain. Islamophobia is a book by Milan Datta; its theme is apparent from its title. Datta writes, “Islamophobia exists in Bengal too but the nature of it, the way it manifests here is different as compared to other parts of the world.” Datta, 71, is a retired journalist, while Islam, 55, is a mechanical engineer by training.

Darbesh’s Rnaridighir Brittanto is his second book. His first, Talaashnama, was published in 2021 by Abhijan Publishers. The book was translated into English by V. Ramaswamy and published by HarperCollins the same year. Talaashnama started as a series of Facebook posts about a young man named Maruf, who, as Darbesh puts it, is trying to pin down the exact reason why the average Indian Muslim never quite achieves his potential. Darbesh says, “The posts elicited a lot of ‘likes’ and started a discussion. Shortly after, Abhijan contacted me.”

Some of the others bringing out books about Muslims of Bengal, their identity, culture, and way of life are Dey’s Publishing, Gangchil, Mullick Brothers, Biswa Bangiya Prakashan and Natun Gati Prakashani.

Shubhankar Dey, who is chief executive officer of Dey’s Publishing, says, “There is a need for delving into history and exploring the past. And people want to read it.”

Saifullah (who goes by one name), 49, has written the books Prak Satchollish Porbe Bangali Muslim Meyeder Sahityacharcha, Charjapad, Sabdartho Abhidhan and William Careyer Kathopokathan. He teaches Bengali at Calcutta’s Aliah University. His hometown is in North 24-Parganas’ Guma town. He says, in the course of his career he has come to realise that Muslims living in remote areas of West Bengal need education, better opportunities and better exposure. He adds, “Among the first-generation learners of the community, there are many talented writers. They want to be heard through their books and poetry, but there are very few publishing platforms.”

In 2018, Saifullah himself started the publishing house Aliah Sanskriti Sansad. Apart from publishing books, it organises discussions, seminars and book readings across the city and also in Murshidabad. The last discussion it organised had for its theme education of the 19th century Bengali Muslim girl child. The keynote speaker was scholar and researcher Swapan Basu. “Through this platform, we want to remind and retell stories of our cultural heritage,” says Saifullah.

The need to establish a socio-cultural identity to counter the “ceaseless typecasting of Muslims” indeed seems to be the pressing need of the hour. Samim Ahmed, 51, who teaches at a college in Belur Math, has written Bharatiyo Darshan, Dharma, O Anyanyo Bhabna and Mahabharate Rajniti o Anyanno Prasanga. The first book, which is about Indian philosophy and religion, has chapters on Sufism, Allama Iqbal and Maulana Azad.

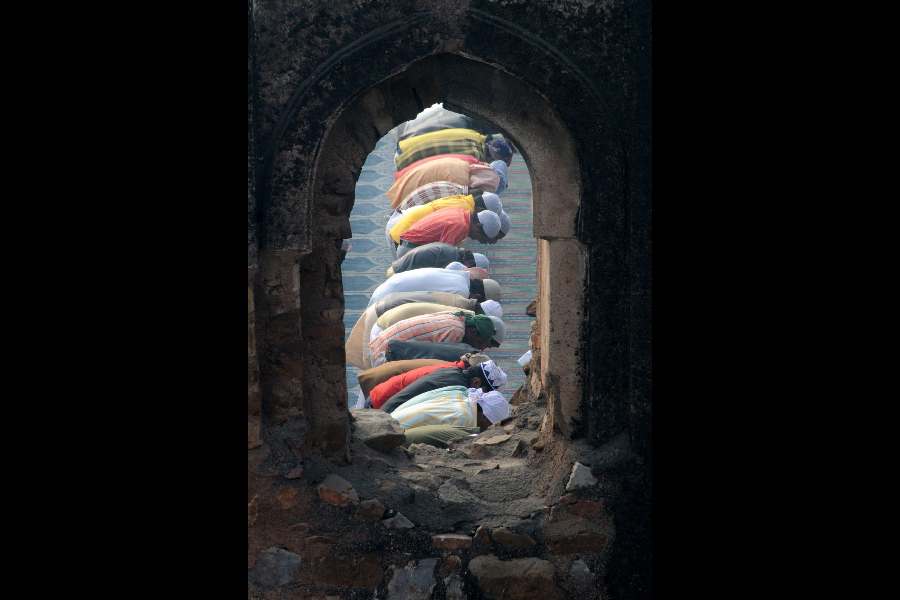

Muslims offering namaz at Feroz Shah Kotla Masjid on the occasion of Id-uz-Zuha festival in Delhi.

The second book is about the politics faced by minorities, and uses the numerical insignificance of the Pandavas in comparison to the Kauravas as an example. Ahmed tells The Telegraph, “My books are a commentary on the representation of minorities. People have a notion about us, our culture, our rituals. The films that we see, the plays depicting Muslim characters reiterate those ideas. I want to show people who we really are.”

Maruf Hossain founded Abhijan Publishers in 2005. Some of his bestsellers are Moynabibir Nao, Go-Rakhaler Kathokatha, Akhtarnama and Comrade O Anyanno Galpo. Of these Moynabibir Nao, written by Waheeda Khanderkar, is about a woman who is haunted by the spectre of the National Register of Citizens. Hossain says, “There might be a number of books on Muslim identity this year but the discussion within the community, between publishers and writers began much earlier.”

'Moynabibir Nao' book cover

Nearly everyone The Telegraph spoke to seem to agree the impetus was the frenetic activity of the BJP and the RSS ahead of the 2019 elections, though the need was long felt.

Some might find the trend reminiscent of a literary churning in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in Bengal. People like Rakhaldas Banerjee and Romesh Chunder Dutt tried to construct a Hindu cultural identity through historical novels such as Sasanka, Maharashtra Jiban Prabhat and Rajput Jiban Sandhya.

Islam says, “The Babri Masjid episode hit us hard. It was not expected in a secular country. Godhra was a wake-up call. Those days, I used to write letters to the editor of a Bengali news daily. My purpose was to foreground that we, the Muslims of India, are not outsiders. We have our contributions too. Can you afford to write the history of India and edit out the Mughal era completely?” He has written books about the history of the Muslims in Bengal and also about their role in the Freedom Movement. His Nalanda Vishwavidyalaya, Dhangsho O Bouddho Dharmer Paton argues that Bakhtiyar Khilji had not gone to Nalanda at all, let alone destroy it. He has cited 13th-century historian Minhaj-i Siraj Juzjani’s Tabaqat-i Nasiri to prove his point.

Dey’s will soon be publishing a dictionary of food names as used by Bengali Muslims.

“There is a need for such books,” says Ahmed. “If we do not know each other, it will be easier for the politicians to influence us.”

Murshid A.M., author and bookstore owner

Murshid says “WhatsApp University” is where people get their education nowadays. He adds, “And since we do not want to know each other, our culture, our background, it is easy for political parties to use us, misuse us and fool us.”