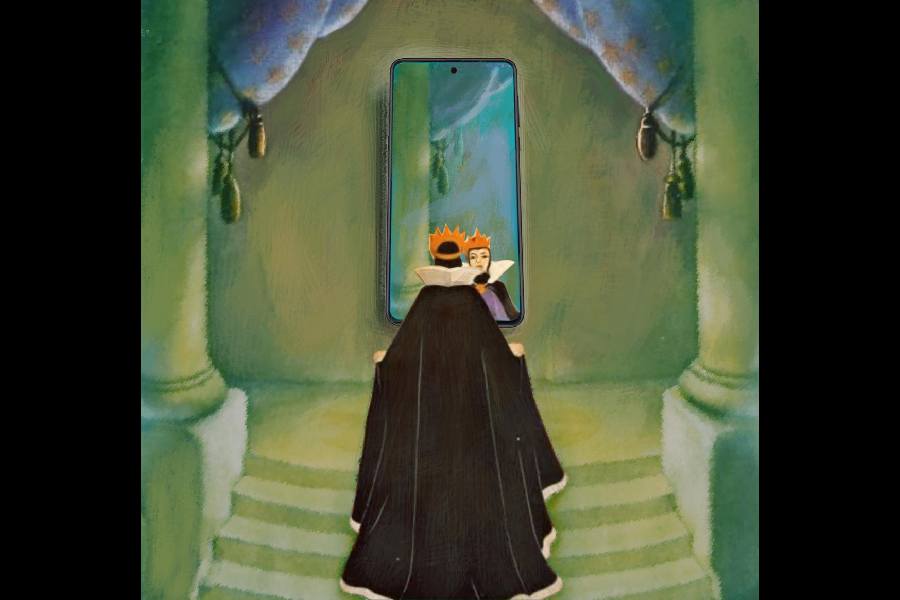

Echo was in love with Narcissus, and the beautiful Narcissus was in love with himself. Immersed in his own reflection, he wasted away eventually, the Roman poet Ovid tells us. Is it possible Ovid didn’t know that Narcissus was Instagramming?

Previous generations of humans have routinely lived, rallied, battled and given up their lives when needed for causes small or big, but most definitely beyond themselves. At least that is how they are remembered by posterity.

What would have happened to the uprising of 1857 if Mangal Pandey had got fixated on waxing his moustache for that perfect selfie? What if, one January night in 1941, before leaving Calcutta and India for good, Subhas Bose decided to post one last picture of his Elgin Road residence, but only after selecting a warm filter and adding the words “auf wiedersehen”?

What if Ashoka had a handle called @PataliPutra and a general run it, and Akbar paused to curate photographs of his beloved bageechas every other day? What if the Rani of Jhansi Regiment chanted “Insta karo” instead of “Delhi chalo” and Marie and Pierre Curie spent a good part of their out-of-laboratory time making reels of their pets Polonium and Radium…

Laugh, but there is little scope for doubt that these times will be the first to raise a large tribe of humans consumed by an obsession with the image of the self.

Sarah Frier’s book on Instagram is titled No Filter. She writes that when the platform debuted in 2010, “Everyone took photos on their phones, and everyone wanted them to look better. Everyone was going to use Instagram.”

She continues, “The filters made reality look like art. And then, in cataloguing that art, people would start to think about their lives differently, and themselves differently, and their place in society differently.”

You have heard about art imitating life. On Instagram and as encouraged by it, the world started to see life imitating “art”.

And what a life it is! People posing instead of being, projecting instead of doing, de-linking the moment from the momentum, trading the reality for the augmented reality, looking skinwards not inwards, and when outwards only at that which will sit well in a 1080 x 1080 Instagram post.

So you have millions — actually 2 billion, which is more than the population of India — posting close to 95 million photos every day. Row upon row of them — faces, bodies, faces, bodies, same face, same body, different settings; same face, same body, different clothing. As photographs they fail, devoid of “aura”. They don’t qualify as mirrors either.

The young flaunt their youth, their physical fitness, their beauty, their fashion, their pets, their plants, their celebrity friends, their couple love. Lots of close-ups. A lot of skin. Whither older humans? Whither the children?

The middle-aged who use the platform flaunt their erstwhile youth, their continuing negotiations with physical fitness, their success, their pets, their plants, their celebrity friends, filial love… A lot of sepia. More long shots and close-ups of bare midriffs…

Many like to feed their Insta handles before themselves; they possibly believe Gaza is an ugly filter. Some people open accounts for their pets. Imagine Bagha Jatin opening an account for the tiger he killed with his bare hands, to post covert warnings to the colonial forces. What if Hitler had Goebbels open an account for his German shepherd Blondi?

Never mind. The point is, no matter how many research papers are written every year on Instagram “filtering feminisms” or its interactive use by Spanish political leaders, and no matter what data you dig up to prove that most content on it is actually covert advertisement, it is a fact that the overarching rationale is to refract all messaging, all intent, all sells and tells through the I-mage. And the people are more than willing.

It is not even like Faust selling his soul to the Devil for a grand bargain that constitutes X years of worldly knowledge and pleasure. Here, there is no point except for the immediate gratification of self, the thrill of seeing “perfect” versions of yourself without any effort, and follower count.

Insta, ergo sum — I Insta, therefore I am.

If Instagram were a civilisation, this would be the beginning of its age of conflict. Thus far, it has flourished, armed with special weaponry to battle and get the better of its only adversary — not SnapChat but RealLife. Chief among them are filters.

Every post comes with filter options with names such as Clarendon and Gingham, Juno and Lark, Sierra, Valencia, Ludwig and even Moon. They are so popular that many name their babies after these, little knowing they are random things like a neighbourhood (Kevin) Systrom lived in, or a street he liked, or a drink he enjoyed. Systrom is the founder of Instagram.

With filters, people have gotten used to things like getting a tan without going to the beach, or achieving clear skin without the exfoliator and a great diet. Instagram filters have reportedly spiked demands for cosmetic surgery. Life imitating art.

But sometimes, like an old habit, art does lapse into the life-like. So you have the odd rebel like Sasha Pallari with an Insta cause. In 2020, this influencer started the Filter Drop campaign, encouraging Instagrammers to post photographs of themselves in their “real skin”, pores, blemishes et al. So much so that today, news sites will curate for you lists of the top No-Filter influencers. There are also the “faceless creators” who imagine themselves to be quite revolutionary. What they actually do is post content without revealing their faces.

If filters are the Instagrammer’s shield equivalents, hashtags are their swords. Watch how they fly — #love (1.835B) #instagood (1.150B) #photooftheday (797.3M) #beautiful (661.0M) #followme (528.5M) #me (420.3M). (The figures indicate the engagement rate of hashtags.) Together they scatter to the margins the non-beautiful, the non-filterable, the insta-bad. And they keep it that way.

There are tools to track hashtag usage, there are hashtag generators premised on analysis of billions of hashtag combinations, and there are AI generators too. You would have heard of Buddha’s eight-fold path. On Instagram, there is the three-fold rule for posts and the 5-3-1 path to grow follower count. It says for every post you make, like 5 posts, comment on 3 and follow 1 new person.

Followers, mind you, not friends. In this world, a Siraj would follow a Mir Jafar, and a Cromwell would follow Anne Boleyn and not think twice. In the real world, Zelensky follows @realdonaldtrump, who follows only a small pool of people, but still follows Melania.

Having enough followers is a big deal. There have been cases of suicide after a denuded follower base. People take great risks for it. Lightning killed 16 people not long ago when they were taking selfies in the rain on top of a watch tower in Rajasthan.

Instagrammers are yet to engage with discordant things like death. Last month, when Pahalgam happened, when India and Pakistan engaged in military hostilities, some of the influencers on this side felt the need to step away from their world of art, beauty and perfection. On many a handle, you would have seen wedged between a celebrity workout video and a brand promotion, the Tricolour. Or after a shot of a hand, attached to a well-recognised face, holding a garland of mogra, a war post, stark. On a date when Pakistani drones were pummelling Poonch, Pathankot, a celebrity video post of a dress-up and a line about the “safety pin superhero”. Not twisting things out of context, just the context twisting.

Like ripples in still and beautiful waters, these interjections from life beyond the pocket square quivered for a while, and then the waters were still again. Perfect.

Narcissus didn’t die, he turned into a flower. Now, our name for it in these parts is phool, sounds a lot like fool. Just saying.