Bengalis have a protrusion around the stomach because they have had to endure the trauma of the famine, said Amina Khayyam. “I learnt about this epigenetic change during our research on the Bengal famine of 1943,” continued the UK-based Kathak dancer.

The research was in connection with one of the many programmes organised last year to mark the 40th anniversary of the UK’s Chatham Dockyard closure. The whole of Britain was caught up in a celebration of its 400-year-old history. A dockyard or shipyard is where ships are built, repaired and maintained. Chatham was one of the main facilities of the UK’s Royal Navy. It built close to 500 ships.

When Khayyam and members of her dance company and hip-hoppers of ZooNation met producers Icon Theatre to decide which stories from the East India Company’s history they wanted to showcase, the Partition was a popular choice. Icon Theatre is based in Medway, where generations have been employed with the Chatham Dockyard.

Khayyam, who was born in Bangladesh, was interested in the Bengal famine. What followed was extensive study and discussion and the end result was a dance production called Ghost Ships.

“Chatham has always maintained a sanitised image of its legacy. I wanted to talk about the other, a much darker side of it. Who used these ships? Where did they go? People here should get the full picture,” Khayyam told The Telegraph over a video call.

The connection between Chatham Dockyard and the famine in Bengal is not an obvious one. When the British Empire was at its peak, this was one of the many dockyards that facilitated trans-Atlantic slave trade. And once slavery was abolished in Britain in 1834, the ships started aiding the East India Company in the export of spices and goods from India to Britain. The two segments of Ghost Ships mirror the dockyard’s double role.

“The preparation took a whole year. At the research and development stage, we worked with historians, familiarised ourselves with visuals of the famine,” said Khayyam. “The image of hunger and desperation stayed with us.”

Chatham Dockyard functions as a giant maritime museum today. Visitors can see for themselves the smithery, the ropery, ships HMS Gannet, HMS Cavalier... In one such part of the museum known as No 5 Slip was staged Ghost Ships, an 85-minute “immersive act” by an ensemble cast of close to 200.

Khayyam said, “During World War II, Winston Churchill used ships to send out food stock from the Indian subcontinent, leaving its own people hungry. There was no real shortage of food, the supplies were just sitting at the docks while the people starved.”

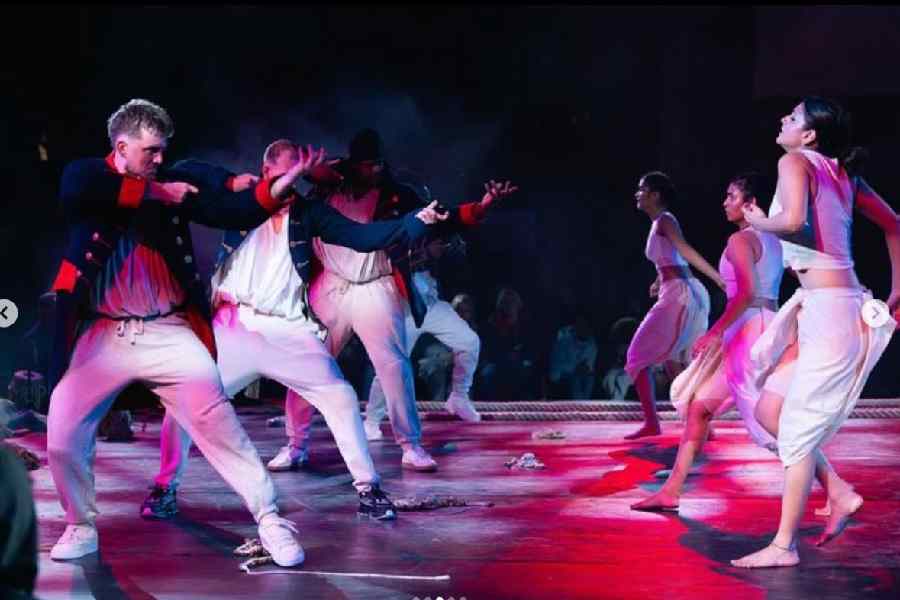

On stage, the famine was depicted through Kathak. There were rhythmic compositions or tukda and footwork compositions or tihai. Khayyam says, “They work like sawal and jawab, a back and forth between two artistes. The British soldiers would fire at the Indians in tukdas and the Indians would fight back in tihai.”

The dancers representing famine victims wore white, short tops and dhoti; their attire soiled and distressed in places. “I did not want us to be all decked up. There is nothing pretty about the story. Half naked, when we stood before those depicting the colonial power, we automatically felt the vulnerability and helplessness of the situation,” said Khayyam.

In his review in The Standard, David Jays wrote: “Kathak dancers zip across the floor with a beguiling rattle of ankle bells. Clive of India wears his redcoat like a boast... As singer Sohini Alam keens, dancers sorrowfully unwind their skeins of bells, the bodies that whirled in joy now crumpling in hunger.” At the tabla was Calcutta’s Debashish Mukherjee.

Khayyam said, “The story of the Bengal Famine had never been told in this scale to an audience in the UK.” She is now getting ready for another performance based on the famine, this time at Somerset House in London.

Some ghosts have a job to finish before they can be laid to rest.