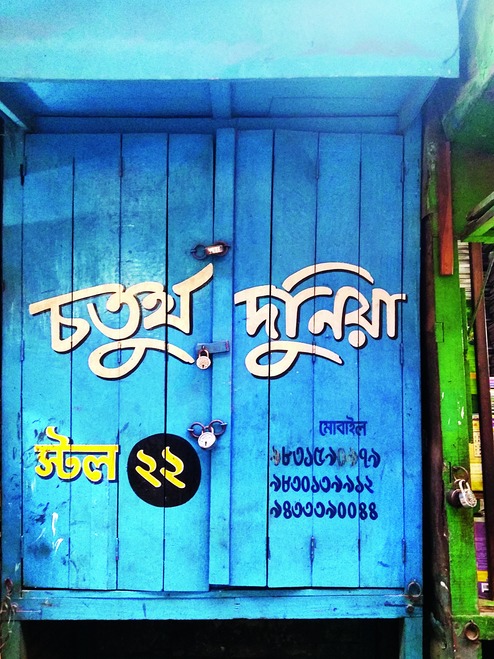

Picture Credit: Prasun Chaudhuri

Stall 22 is like no other on Calcutta's College Street - four-feet-by-three-feet, its shutters a copper sulphate blue. Recessed from the main road, which has a tramline running through, it is wedged between a shop selling new and old Hindi literary works and another selling old textbooks. Stall 22 is there but not quite there. No matter what time of the day you turn up, the wooden shutters are firmly shut. Written across them in white Bengali font are the words - Chaturtha Duniya, meaning the fourth world.

It is late afternoon and our nth visit but the shop is not open. The loopy accents below the " taw" and "daw" look like eyes with a sad faraway look. We wait for the salesman of the adjoining stall to be done with his haggling customer and then ask if he has any idea when the stall opens. "Tomorrow," he replies curtly. Disbelieving, we start to dial one of the numbers painted on the shutters. The phone rings as usual, only this time, someone receives the call.

It turns out to be Manohar Mouli Biswas, president of the Bengali Dalit Literary Association. He repeats what we have just learnt. "We open the stall every Thursday evening, around 6.30."

Call me charal, chamar, dom/

I have to listen to these insults every day...

Kalyani Thakur Charal

Chaturtha Duniya is stocked with books - fiction, non-fiction, poetry - by Bengal's Dalit writers. The epic historical novel, Ujantalir Upakatha (The Lore of Ujantali), by Kapil Krishna Thakur, Kalyani Thakur Charal's autobiography titled Keno Ami Charal Likhi (Why do I call myself Charal), a collection of poems Kshama Nei (No Forgiveness) by Nakul Mullick, an anthology of Bangla Dalit writings, and so on.

According to Biswas, Charal literature or the Dalit literary movement in Bengal traces its origin to the Dalit Literary Meet in the state three decades ago. The word " charal" is a corruption of the Sanskrit word "chandal", which is often used as an umbrella term for Scheduled Castes.

Jatin Bala

The movement culminated in the birth of Chaturtha Duniya, a literary quarterly, in 1994. "When we realised that mainstream publishers are not interested in the Dalit voice, we started the magazine," says Biswas, who used to be an employee of the state-run Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited until 2003 and turned full-time writer and editor thereafter.

Continues Biswas, "Now, apart from the magazine, we publish all genres of Dalit writing. There are over 100 writers of the novel, short story, poetry, drama, essay and autobiography. Some of the voices have been translated into English and other Indian languages."

Aspiring Dalit writers flock to Chaturtha Duniya regularly to discuss writings and seek advice from senior writers. They sit on plastic stools by the stall to discuss creative pieces for upcoming books as well as the quarterly over steaming cups of cha. Dalit literary meets are organised and aspiring writers are encouraged.

This new genre of literature from Bengal was birthed in relative silence with the tacit support of the exponents of its Marathi counterpart. "Inspired by the ideologies of B.R. Ambedkar, Dalit voices unleashed a typhoon in Marathi literature," says Jaydeep Sarangi, an academic and co-author of Dalit Voice: Literature and Revolt, which covered the Dalit situation in different parts of India.

Ambedkar had harped on the importance of education among Dalits to change Dalit lives. His efforts at establishing several educational institutions galvanised a new generation of educated Dalits, who then started questioning certain tenets of Hindu societal structure. Their angst culminated in the Dalit Panther movement led by literary giants such as Namdeo Dhasal. And this movement, in turn, yielded literature that was in stark contrast to existing Marathi literature, which took little note of social issues and concentrated on romanticism or nationalism instead.

"Twenty five years ago, Poisoned Bread, the English translation of an anthology of Dalit writings in Marathi, created a literature of protest in several pockets of India - Gujarat, Andhra, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, etc.," says Sarangi.

The collection gets its name from the eponymous tale by Bandhumadhav about Yetalya Aja, a Mahar by birth and slave of landlord Bapu Patil. Aja dies after he's abused and forced to consume pieces of stale bread covered with dung and urine. As he lies dying, he tells his grandson, "Get as much education as you can. Take away this accursed bread from the mouths of Mahars..."

Poisoned Bread was published in Bengali in 1994. Bengal's Dalits had broken their silence at last.

Before Partition, Bengal's Dalit community, locally referred to as Namasudra, was concentrated in East Bengal, in the districts of Khulna, Faridpur, Jessore and Barisal. Nearly two crore in number, they were primarily tillers of land, scavengers, morticians and cobblers. Though they were a vital force in society, they were economically deprived and hugely exploited. They bridged the necessities for the higher castes but remained human hyphens, being the liminal and also living it. In time, the professions they espoused became part of their names and by association came to connote abuses. Poet Kalyani Charal cites some instances from the Bengali language - chandal raag or rage like a chandal's, churi chamari or as thieving as a chamar, and chashare achoron or uncouth like a farmer.

Post Independence, fearing communal violence, the community migrated to West Bengal. Unlike the upper caste migrants, they were largely rehabilitated in inhospitable geographies - the islands of Andaman, the Dandakaranya forests of Odisha and so on. Thus scattered, the community lost its cohesive character.

The Namasudras living in the eastern parts of Bengal were among the first to receive education. They had been inspired by social reformers of the community such as Harichand and Guruchand Thakur.

Aided by education, the new generations started to question what their forefathers had accepted as their fate. A lot of the rage was against the Leftists. Says Biswas, "The community had helped the Leftists topple the Congress government in 1977. But far from rising above caste differences, the Left government unleashed atrocities on hundreds of Namasudras in Marichjhapi [an island in the Sunderbans] and later in Nandigram." In the late 1970s, when refugees from Dandakaranya began migrating to Bengal, the government goaded them to go back. Finally, on January 31, 1979, police opened fire in Marichjhapi, when the migrants, who had built a thriving community life there, refused to leave. In Nandigram, too, countless villagers - mostly Dalits - were killed in police firing when they protested land acquisition efforts by the state government for a chemical industry.

Politicial theorist and activist for Dalit rights, Kancha Ilaiah, once said, "Communist ideology in Bengal has kept other ideologies under its hegemony. Upper-caste intellectuals failed to give space for Dalit intellectuals to thrive."

The battle wounds of Marichjhapi and Nandigram continued to fester. But perhaps for the first time, a section of the community attempted to avenge the bloodshed by ink.

In his book of poems, The Wheel in Turn, Biswas writes, "...I am a Dalit in this country/And by my humble origin, a proletariat/I have the strength and thought/ To knock at the door of equality... With angst I dream of breaking the rigid posts of authority." Biswas, who rose through the ranks, makes sure to tell The Telegraph that he never fell back on quotas for help.

Kalyani Charal portrays the undercurrent of casteism running through the psyche of the educated middle-class Bengali. In the poem, Chandalinir Kobita she writes, "My colleagues in office/Call me charal, chamar, dom/I have to listen to these insults every day... Even then I have to remember that/In Bengal there is no such thing as a 'Dalit'/Even if Dalits exist everywhere else in the world, here there are none/Everywhere in India there may be castes/ But here there are none..." To protest the hypocrisy of the bhadralok, Kalyani, who was a vegetable vendor before she got herself a job in the Indian Railways, likes to wear her Charal identity as part of her name.

Jatin Bala, who has written Sekor Chhera Jibon (An Uprooted Life) and Samaj Chetanar Galpa (Stories of Social Awakening), compares the current wave of Dalit literature with the African-American literature of protest in the US in the 1920s-1930s.

Biswas points out that the wealth of Dalit writing is getting discovered now. He says, "Many universities in India and abroad now include our pieces in literature courses." Adds Bala, "Until recently, we had been more popular with academics. But now we are getting attention from a larger audience."

It is not as if mainstream Bengali writers have not talked about Dalit lives - Tagore's Chandalika, Barishaler Jogen Mandal by Debesh Ray, Padmanadir Majhi by Manik Bandypadhyay, to name a few. But there is apparently a difference. Says Manoranjan Byapari, "Manikbabu, a Brahmin, has failed to paint any of the characters in the novel perfectly. If you see it from the perspective of a Dalit, it is full of flaws." He points out that in contrast, Dalit writer Adwaita Mallabarman's Titas Ekti Nadir Naam is a more accurate depiction of the community. According to Byapari, who has written the autobiographical Itibritte Chandal Jibon ( Interrogating My Chandal Life), Dalits write their stories with "empathy", but when non-Dalits talk about Dalit lives, they shower "sympathy".

A short story, Fatna, by Jatin Bala comes to mind. In it, Bala writes about a character called Rajen, who half crazed from hunger and poverty has lost all sense of ethics. So strong are his pangs of hunger that he cannot wait to skin the cow he owns and so dearly loves, which is now ailing and on the brink of death.

The copper sulphate Stall 22 is not quite like any other on College Street, nor the world it acts as a window to.