|

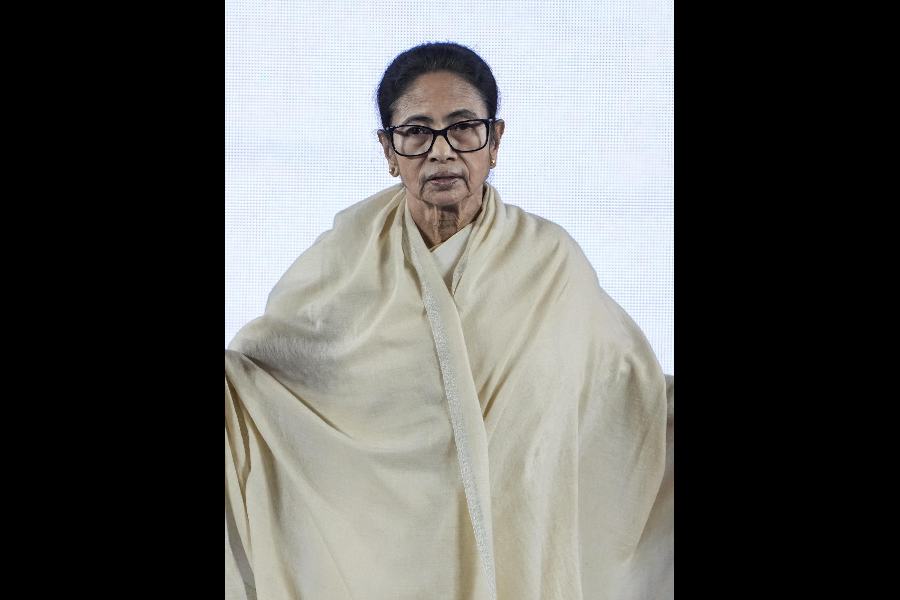

| Soumyajit Roy and Pei Liang |

New Delhi, Aug. 3: A feast of circles for the eyes may help make some food sweeter to the palate.

Scientists in Changshu in eastern China and a collaborating Indian researcher in Mohanpur, Bengal, have found a new way to alter perceptions of sweet taste in humans.

Indian materials scientist Soumyajit Roy and Chinese neurobiologist Pei Liang — a husband-and-wife team — and their colleagues have shown that gazing at geometrical figures or even familiar words enhances the ability to detect sweetness.

“We’ve known for long that nice-looking food tastes better than bad-looking food,” said Liang, a researcher at the Changshu Institute of Technology in eastern China. “Our work now suggests that visual cues that have nothing whatsoever to do with food can also influence taste.”

In laboratory experiments, the scientists observed that volunteers asked to sip water while peering at circles or ellipses on computer screens reported the water as sweet although its sugar level was so low as to prevent it from tasting sweet. They found a similar increased sensitivity to sweetness when volunteers were shown familiar words, such as James Bond’s secret code 007 or the name Mai Dang Lao, Chinese for McDonald, on their screens.

“Like beauty, taste too lies in the eyes of the beholder,” Liang told The Telegraph. The study’s findings have been published in the journal Behavioural Brain Science.

Their results bolster evidence for a notion gaining ground among psychologists that tasting is a multi-sensory experience that draws on not just the aroma and taste of food but also on what the eyes see during the act of eating or drinking.

Researchers believe this phenomenon, called cross-modal correspondences, may have some real-world applications — from helping the overweight or patients with diabetes appreciate low-sugar food to guiding chefs or the food industry with strategies to keep customers happy.

Roy, a materials scientist at the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, Mohanpur, had never heard of the phenomenon when he first tasted a traditional Chinese sweet — long xu tang, or dragon’s moustache — at Liang’s home in Bielefeld, Germany, in 2004 where they were both students. For Roy, who was born and bred in Bengal and revelled in its abundance of sweets, long xu tang appeared to contain no sugar at all.

His long-simmering interest in psychology intensified during their six years of courtship. And in 2010 — a year after they got married — Roy proposed the experiments to study the effect of vision on taste during an after-dinner stroll in Changshu, where he is a visiting faculty member.

Their study, led by Liang and conducted in the sensory sciences laboratory headed by biologist Gen-Hua Zhang at the Changshu Institute, did not find any effect on the sensitivity to sweetness when volunteers — university students — gazed at a triangle, a rectangle, or a pentagram.

The researchers observed volunteers showing an increased sensitivity to sweetness only when the sugar concentration in the water was close to 3.1 gram per litre, slightly below the threshold for sweetness. The shapes and words had no effect on taste when the water had too much sugar or had no sugar at all.

The scientists speculate curved shapes such as a circle or an ellipse and familiar words induce greater cognitive ease — make a person feel comfortable — than would a triangle or a rectangle, or unfamiliar words.

“This feeling of comfort enhances the sensitivity to sweetness,” said Roy. “And the shapes with sharp angles don’t induce such comfort because sharp angles may evolutionarily be associated with discomfort, for instance sharp corners may hide lurking danger.”

Unfamiliar words also induce cognitive strain which, Roy and Liang believe, leads to additional mental workload which, in turn, reduces the sensitivity to sweetness.

Earlier this year, Charles Spence at the University of Oxford and his colleagues demonstrated that the colour of cups influences the taste of hot chocolate — the same hot chocolate seems to taste better in an orange or cream coloured cup than in a white or red coloured cup. Their study was published in the Journal of Sensory Studies.

“(Such) findings open up a whole new way of thinking about matching tastes and flavours to shapes, colours, sounds, and even musical instruments,” Spence, professor of experimental psychology at Oxford told this newspaper.

Several studies over the past decade have shown that the brain has a tendency to match sensory features across distinct senses — such as shapes and smells, or shapes and sounds. The China-India study now links shapes and tastes.

“High pitch sounds are associated with smaller shapes, bright colours, and high elevation in space, while low pitch sounds with big, dark shapes and lower elevation in space,” said Ophelia Deroy, a Marie Curie Researcher at the University of London.

In one experiment, Deroy and her colleagues asked people to pair beer they tasted with angular, round, or complex shapes and found that round shapes seemed to be associated with sweet taste while angular shapes were linked with bitter taste.

“The two key questions about such correspondences are: where do they come from, and what are their effects?” Deroy said. “But this is a very pervasive phenomenon — the (19th century) French poet Charles Baudelaire talked about this phenomenon in his 1857 poem titled Correspondences.”

Liang said the exact brain mechanisms underlying these correspondences is yet to be understood. She and Roy are now hoping they can continue similar experiments in India to determine whether the effects also show across different cultures.