|

Calcutta, April 25: Amit Mitra’s agony was Saradha’s ecstasy but the stoical finance minister seems to have suffered in silence instead of prescribing a painkiller.

Companies illegally mobilising deposits appear to have sucked dry one of the most preferred sources of loans for the debt-burdened Bengal government in the past two years, forcing it to tap markets with narrower repayment windows.

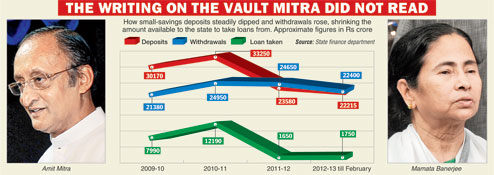

Official data show a steady slide in small-savings deposits and a spurt in withdrawals, which left a thin slice for the state government to borrow from to make ends meet (see chart). Bengal had ranked first among states in deposit mobilisation several times when the Left was in power.

“It is clear from the data that people were withdrawing more than depositing in these schemes…. As the deposit-withdrawal ratio was negative, the government could not borrow much from the small-savings pool,” said an official.

According to him, the negative deposit-withdrawal ratio made it clear that people were diverting money from safe small-savings schemes into riskier schemes that promised unrealistic returns — such as those run by Saradha and others across rural Bengal.

Chief minister Mamata Banerjee has said she did not know that the so-called chit fund companies were illegally mobilising deposits in the state. But sources at Writers’ said the numbers were readily available with Mitra’s department as well as in the Economic Review and a cursory glance should have set alarm bells ringing.

“The finance minister is supposed to know about collections for small savings as the pool has been the biggest source of government borrowing for years. He should have noticed the dip and informed the chief minister,” said a senior state government official.

Mitra, who has not commented on the deposit default crisis in public although the government has announced an additional tax to bankroll a relief fund, was not available for comment today despite repeated calls from this newspaper.

A debt-stressed government can tap either the market or the small-savings pool for working capital management.

Finance ministers usually find the small-savings pie delectable as it offers a moratorium on repayment of the principal for six years whereas the repayment burden on market borrowings kicks in immediately. Besides, the repayment period in case of market borrowings is between eight and 12 years while loans from small savings can be repaid in 25 years.

Although the 8.5 per cent coupon rate on market loans, which depends on the state’s creditworthiness, is a few percentage points lower than the 9 per cent rate of interest on loans from small savings, most finance ministers tap the market only after exhausting the small-savings option.

“The biggest advantage of the small-savings option is that the loan amount is available on the first day of the month, which makes working capital management easy for the government,” said an official.

In 2011-12 and 2012-13, the state clocked record market borrowings — Rs 22,190 crore and 21,100 crore respectively — as it was left with no other option.

There is no conclusive proof yet that the dip in the small-savings collection happened because of the proliferation of deposit-mobilising companies. But a city-based economist said there was “certainly a certain degree of correspondence” between the two.

“Several factors like the reduction in the rate of interest and a slash in commissions for agents may have contributed to the decline. But there is little doubt that the savings have been channelled to the so-called chit funds,” said the economist.

At present, the average return from small savings is around 8.2 per cent, which means it would take around 8 years for the principal to double itself. But many deposit-mobilising companies have been promising to double the principal in five years.

For two small-savings schemes — the public provident fund and the senior citizen savings scheme — there is no commission for the agents. For another six schemes, the agents get 0.5 per cent to 2 per cent commission, which is set by the Centre.

“Companies like Saradha used this opportunity to lure agents who have already earned the faith of the rural populace by working as government agents. They were offered high rates of commission ranging from 20 to 30 per cent of the deposits,” said an official at the small-savings directorate.

The directorate, with 20 regional offices across the state, is supposed to look after small-savings collection and monitor the activities of the agents who sell the schemes to the people.

“The small-savings directorate had written to the finance department that many of the 33,000 government- authorised agents were encouraging people to deposit money with deposit-taking companies. But the warnings fell on deaf ears,” said an official.

The finance department was given specific examples of areas like Siliguri, Durgapur, Burdwan, South 24-Parganas and North 24-Parganas —sources of high savings mobilisation for years — where the deposit-withdrawal ratio remained negative throughout 2011-12 and 2012-13.

“No one in the government cared,” the official said.

According to him, the directorate tried to organise awareness programmes about the risks of schemes that promise high returns but in the absence of support from the finance department, the efforts did not yield much result.