|

| The reservoir near Ultadanga on the land Bird says belongs to the company. (Below) The sign outside Bird’s office on NS Road, still showing the old name. Bachchan used to work in this office. Pictures by Pradip Sanyal |

|

Calcutta, Nov. 7: Some half a century ago, a Calcutta company had provided a tall young man with a job before he went on to conquer Bollywood. Today, some of the old hands in what remains of the firm wish half in jest that Amitabh Bachchan would pay off an old debt.

As the Mamata Banerjee government gears up to welcome Amitabh as the chief guest at the Calcutta International Film Festival on Sunday, the actor’s former employer has accused a Trinamul-run civic body of grabbing its land with tacit support from the state administration.

With the dispute between Birds Jute and Exports Limited (BJEL) and the South Dum Dum municipality showing no signs of resolution, some company employees have been joking about seeking Amitabh’s intervention.

|

| Bachchan in Calcutta in 1972 during an awards event |

In the 1960s, Amitabh worked with Bird and Company, a British-owned firm established in 1904 that the central government took over in 1974. Since the company’s paper mills and coalmines were merged with other central government undertakings, its jute arm alone has been carrying the Bird name.

“The chief minister has a very cordial relationship with Amitabh…. Wish we could have reached him to put in a word for our company when he comes to Calcutta,” said an elderly BJEL employee.

Amitabh has often spoken about his days in Bird and Company. “Kolkata... Calcutta then... first job as executive in Bird and Co... salary Rs 500 per month, after cuts etc Rs 460!!,” he had tweeted in 2011.

Company old timers say Amitabh used to work at Bird and Company’s head office, 4 Netaji Subhas Road, behind Writers’.

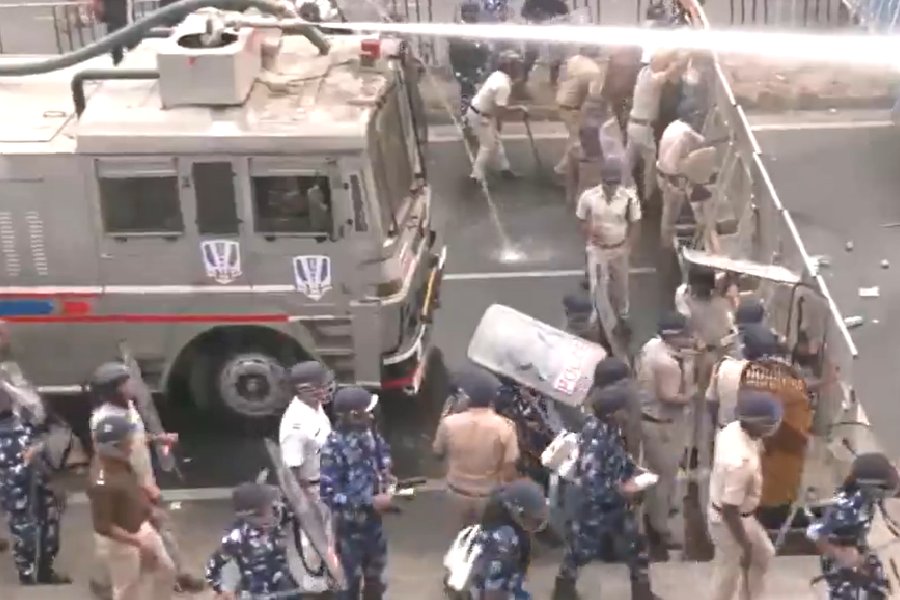

Over the past 23 months, BJEL has been trying in vain to get back what it says is its land — around three cottahs in its 49-acre jute mill compound near Ultadanga. The civic body has built a reservoir on a part of the mill, whose boundary walls have been ravaged by time and encroachers since it stopped production in 2002.

The dispute has now gone beyond mid-level civic and state officials and reached the highest level of bureaucracy. Zohra Chatterji, secretary to the Union textile ministry, wrote to Bengal chief secretary Sanjay Mitra on August 7 requesting removal of the encroachment.

A Writers’ Buildings official said: “Nothing has been done yet; not even enquiries with the civic body.”

Company sources said they had first lodged a police complaint in December 2011 after noticing activities for building a water reservoir on the plot. But the police allegedly took no action.

In June 2012, the company approached Calcutta High Court, which stayed the construction the same month. But BJEL officials allege the construction went ahead, and no one from the municipality or the government made any attempt to settle the matter.

“Then we filed a contempt petition in the high court in April this year,” said Ashok Chandra, who had retired from the company in 2006 but is still on extension.

The company now has just 12 employees at its head office, all re-employed after retirement, who look after whatever little work is left. The only people on the mill compound are a few private security guards.

Sources said the Centre had recommended in 2004 that the company be wound up. But it changed its mind last year and decided to revive the firm. The revival process is yet to start.

“Although ours is a sick company, no one can grab our land,” said an employee. He said the reservoir’s construction, apparently with Urban Renewal Mission funds, had been completed despite the court stay.

Sujit Bose, Bidhannagar MLA and vice-chairman of the South Dum Dum municipality, said the civic body would soon start operating the reservoir.

“This is a project that will benefit thousands of people; it’s not for individual gain. There are numerous places within the mill that have been encroached on but the company isn’t concerned about them. I don’t know why they are up against a project that will benefit the common people,” he said.

Bose added: “The company also has Rs 2 crore in outstanding taxes to our municipality.”

A senior Union textile ministry official told The Telegraph the ministry wanted the reservoir demolished since it had been built without its permission.

“It would have been an entirely different matter had they sought our permission before building it. One cannot just begin construction on another’s land without permission,” the official said.