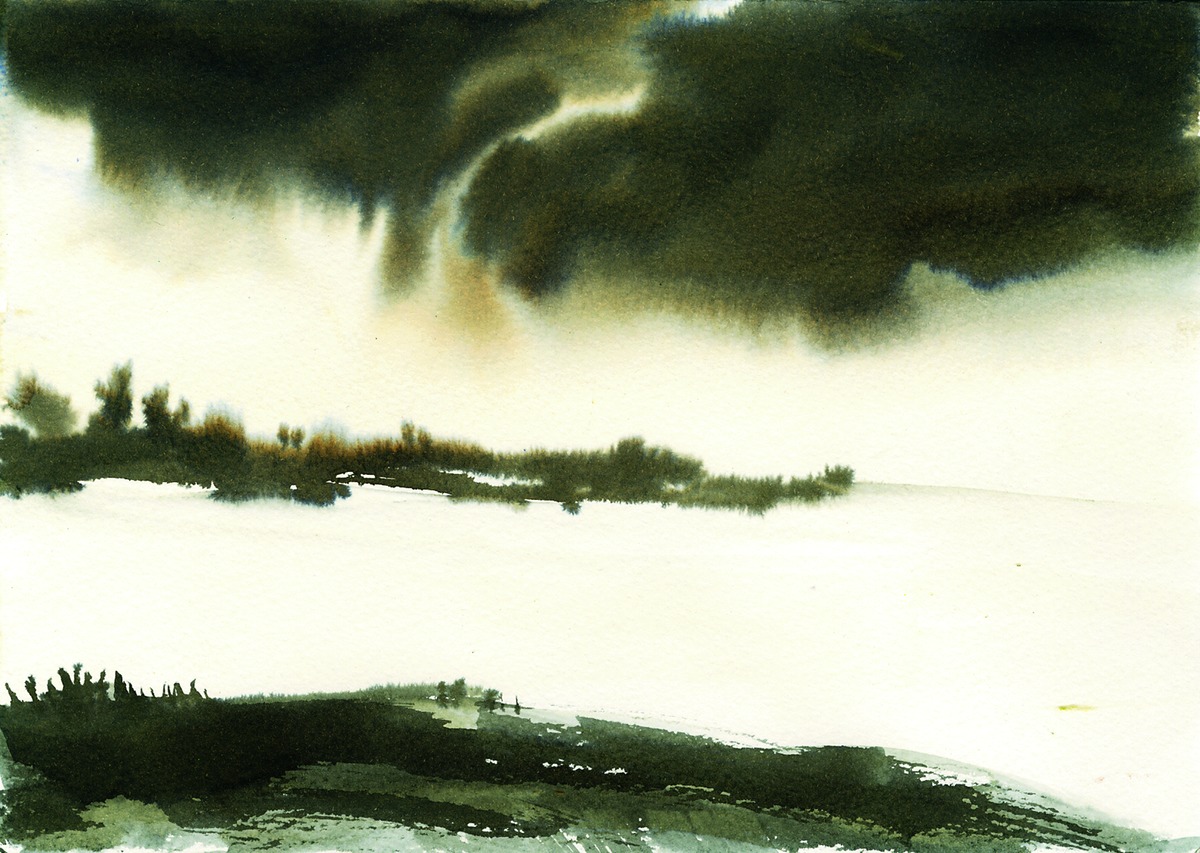

A few more weeks and it will be a memory, this. The swollen clouds heavy with rain, the relentless rain pouring down on the earth like a zillion ringing needles, the earth so wet and the waters even wetter and the skies perhaps wetter than they, and so out of joint too in so many places, made weaker at the roar of thunder, coming undone at the lightning bolt, and once again pouring forth... Garaje ghata ghana, kaare ri kaare...

And yet, truth be told, in a country such as ours, rain and the paraphernalia of it may well ebb out of immediate seasonal reality but they are never quite out of our lives and memories, individual and collective. They keep drumming on the senses, playing on a myriad impulses, they create and connect streams of consciousness and rivulets of creativity... Garaje ghata ghana damakata damini/ Pawana chalata sananana...

We meet Hindustani classical vocalist and Padma Shri Pandit Ajoy Chakraborty at his south Calcutta residence after a week-long wait. The place of our appointed meeting is also the space of his sadhana, we gather. There are half a dozen tanpuras on a raised platform to one side of the room. On a facing wall there are photographs of his guru, M. Balamuralikrishna. Awards aplenty crowd a low glass table.

When Pandit ji walks into the room, he seems buoyant of mood. And a namaskar later, he expresses his amusement at the topic of our conversation that day - monsoon ragas. He asks, " Erom motibhrom holo keno... Why this misadventure."

He begins at the beginning, with how the Malhar group of ragas and the Kannada group have the maximum number of songs suited for the monsoon season. He talks about how Pandit Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande, a musicologist from Maharashtra, was the first to write a modern treatise on Hindustani classical music - which till then largely drew upon an oral repository - in the 20th century. He says how Bhatkhande laboriously classified the ragas under 10 thaats or scales - Bilaval, Kalyan, Khamaj, Bhairav, Poorvi, Marwa, Kafi, Asavari, Todi and Bhairavi. The monsoon ragas fall under thaat Kafi.

In the 17th century, Carnatic music exponent Venkat Mukhi Swami had developed the melakarta - the Carnatic equivalent of thaat - system. Basically, he classified the ragas under 72 melakartas or groups of notes. Says Panditji, "Compared to Bhatkhande's classification, this was more scientific in my opinion." He breaks off, scans our expression, pauses and then resumes in a different strain this time. "No monsoon raga, or for that matter no raga, is dependent on swar or the musical note alone. The sur or melody created from the notes is more important and so also the rendition. Raag sur diye srishti hoyechhe, swar diye noy." Meaning, the raga is born off the melody, not the notes.

From time to time, he breaks into song to amplify his words and thoughts. How a komal gandhar, komal nikhad and shuddha nikhad together mimic the rumble of the clouds, make up the Mian ki Malhar, how an added shuddha ga tweaks and turns it into a Ramdasi Malhar, another komal dhaivat thrown in and it becomes Mira Ki Malhar. How the oscillating notes recreate expertly the monsoon sky, and the repetitions the sameness of drop upon falling drop. But even that, it seems, is not enough for that perfect gayaki. "Expertise goes to waste if not buoyed by the right bhaav or feeling," says Panditji.

He says, "The terror of monsoon", and sings out " Gagana na maradale baaje dhama dhama/Badara natabara naache chhamchham". He sings out again, "Garaje garaje rasa bundana barase," and says, "The fragile beauty of monsoon." And then again, " Aakul birohini ke nainan mein peer bhare... Jo andar tyo bahar chhai ghata kamini ke jiya tarse." And exults, "Above all, monsoon is about love, longing and surrender and Malhar conveys that whole range."

Pandit ji had spoken of the close association of monsoon and kavya. Music historian Lakshmi Subramanian, too, talks about this. She says, "Monsoon produces an aesthetic delight. It is not for nothing that you have the rich varsha repertoire of Tagore." She brings up Valmiki's description of varsha and Kalidas's Meghaduta.

The myths about the Malhar come up. Tansen, it is said, could set alight a thousand diyas with his rendition of Raga Dipak. Likewise, it is said that he could make the skies weep when he sang the Malhar.

It reminds us of what Pandit ji had said about the time when he visited IIT Kharagpur. It was a muggy June noon and his hosts requested him to sing the Malhar. An hour later, when he stepped out, the campus was rain soaked. He had said, "My hosts credited me for it, but I believe that if at all it had anything to do with my music, it was the impact of a combination of notes on nature."

Subramanian too says, "Myths [such as the one about Tansen] indicate psychological reactions [to the ragas]. If you listen to certain songs, you feel good or bad, hot or cold. But, of course, one crucial aspect is timing. For example, when you hear Birendra Krishna Bhadra's Mahishasuramardini, it is most likely that the effect will not be optimum if you tune in in the middle of January."

When we met Pandit ji that July evening the sun was beating down on us. By the time we took his leave, it was drizzling. The rain pitter-pattered on the asbestos shade covering the back door as we followed the trail of frangipani fallen on the grass.

The day we meet percussionist-composer Bickram Ghosh, it is cloudy. One of the drawing room walls is all glass, overlooking a cluster of eavesdropping peepal, radhachura, krishnachura. He talks about how he attempts to capture the essence of the monsoons on "a low sa tabla". "The tabla, as we play it, is usually at a high mid frequency. But the low sa has gravitas like the pakhawaj - a variant of the mridang - which in turn mimics the thunder." He recites a bol in determined baritone, hard rhythm in place, Dar daar drumaka/Gadi naar, drikata/Baaje mridanga tar taar re/Dene daar prakata/Brahmaand thararara/Nataraj se...

The chant, quick-paced, onomatopoeic, a flurry of edgy consonants conjures a turbid horizon turning inky, knotty clouds, twisting into knots that grow bigger and bigger, heavy and heavier, till their rumble and roar and imploding lightning has all of nature crouching, shivering. Outside, as we can see through the unimpeded glass, it has started to rain. The point Ghosh makes is that the pick of raga must be complemented by the percussion to convey the desired mood, atmosphere even. It will never do to mix the aggressive Dhamar taal of 14 matras with the benign Pilu. But it will enforce the Malhar.

But not all of monsoon is about aggression or weightiness. How does one convey the sweetness, the lightness of a drizzle? By using the Dipchandi taal, replies Ghosh. Unlike the Dhamar's ka dhita dhita dha/Ga dhina dhina ta, the Dipchandi goes dha tik dha dha tin/Ta tik dha dha dhin.

Ghosh had spoken about the Megh Raga, and so does classical singer-cum-music critic Meena Banerjee. She says, "There are 18 to 20 varieties of the Malhar. And among them is the Megh Raga, which some refer to as Megh Malhar. Its structure is pentatonic, meaning only five notes are used. The ga and dha are excluded." She continues, "It is one of the oldest ragas. I had heard it in a melody in Kinnaur [in Himachal Pradesh], in Buddhist chants, Chinese folk songs and pahari songs."

Banerjee talks about how delivery is key to all ragas. "The chalan is important. Just as the clouds vary with the seasons and so do their movement, so must the ragas. The tone of the Megh and any other monsoon raga must be gambhir, sombre." She points out that the popular item number, Munni badnaam hui, is also based on the Megh Raga. "But do we call it raga," she asks. "Matter of delivery," she repeats, at our expression of surprise.

We are meeting Padma Shri Ustad Rashid Khan, from the Rampur-Sahaswan gharana, at his academy, a few days after we have spoken to Ghosh and Panditji. Throughout our conversation, it rains torrentially, the downpour drowning out the sounds of riyaaz emanating from some of the other rooms, even interrupting Ustadji's mellifluous and chaste stream of Hindi.

He talks about his own composition based on Megh Raga, Aai barkha rum jhum ke/ Pawan chalata sanana purwai. His voice drizzles. Among his favourites, he says, is Ai badra barasana ko ai. He names some of the sub-genres under the Malhar - Jain Malhar, a combination of Raga Jaijaiwanti and the Gaud Malhar. "Jaijawanti is sung in low notes to create a heavy feeling and the second one is replete with rapid, gushing notes."

There is also the Madmat Sarang, another raga sung during this time. He says, "It extensively uses high notes at a fast pace to recreate the chanchalata or the nimbleness of the falling rain. The way it is sung, the effect is one of the core being dissolving in the earnest first showers. The voice has to be brimming with a liquid quality and the kashish should be as artful or artless as nature itself."

Ustad ji too has a rain story. He talks about one summer when he was in Jamshedpur at a friend's. It was extremely hot, the way it gets in those geographies, and his friend requested him to sing the Mian Ki Malhar. "Ta ki thodi thandak aa jaye," Ustad ji quotes his friend. Then says, "I submitted humbly, meri itna aukat kahan and presented two songs, Karim tero naam and Aai badra barasana aai."

That night, he tells us, it rained very heavily. So heavily that the water entered people's homes. Garaje ghata ghana...