New Delhi, May 4: A Supreme Court bench, which earlier ruled that mere membership of a terror outfit cannot be a crime, today disagreed on whether a person accused of criminal conspiracy to set off blasts is entitled to bail pending trial.

Justices Markandey Katju and Gyan Sudha Mishra disagreed sharply in open court, following which Katju referred Abdul Nasser Madani’s bail plea back to Chief Justice S.H. Kapadia.

The bail plea will now be placed before another bench, possibly a larger one, to avert a stalemate.

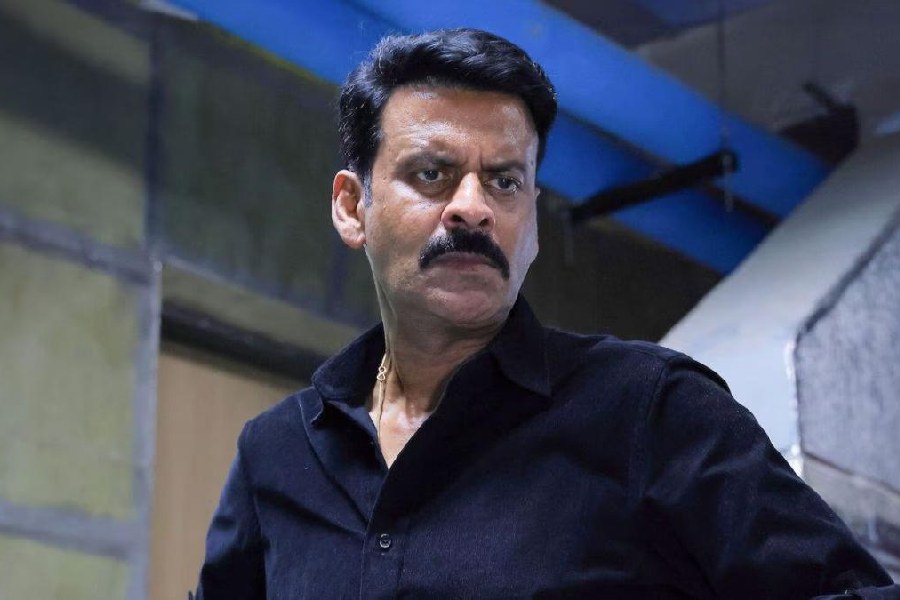

Madani, the leader of the Kerala-based People’s Democratic Party, has been charged in connection with the Surat, Ahmedabad and Bangalore blasts. Arrested by the Karnataka government last August, his bail plea was turned down by the high court in February this year.

Justice Katju rejected the Karnataka police charges against Madani and insisted he could be freed on bail under stringent conditions so he does not tamper with evidence or witnesses.

“This is my opinion and I am entitled to it,” he said.

He shrugged off the prosecution case against Madani, saying that nowhere had the co-accused alleged he had been running training camps for jihadis.

“He may have made some inflammatory speeches which he should not have. One should not use such strong words in a secular country,” he said, dismissing the police evidence against him as questionable.

“They don’t have the scientific skills to gather evidence,” he said. Under pressure to show results, the police arrest on the basis of suspicion and later concoct evidence against the accused, he said.

Justice Katju accepted the argument of Madani’s counsel that not granting him bail would amount to a violation of his right to life. “Then strike off Article 21 (guaranteeing right to life and liberty) from the Constitution,” senior counsel Shanti Bhushan had argued.

“The fact that he is a respected Muslim leader has always been a sore point with Karnataka police,” Bhushan claimed.

At one point, Justice Katju drew a parallel with the Binayak Sen case where two lower courts had found him guilty of sedition but the top court granted him bail.

Karnataka counsel T.R. Andhyarujina objected to the analogy, saying one could not compare an individual charged with sedition to a person accused of conspiracy to set off bombs simultaneously at different places.

Andhyarujina opposed bail for Madani, saying there was enough material to believe he may have been involved in the conspiracy. “Releasing him would have serious security implications.”

The counsel cited repeated phone calls made by Madani, the contents of which were not known, and statements by witnesses and co-accused to police to show that Madani was running training camps for jihadis.

Justice Mishra agreed with his assessment.

“(If bail is to be granted to Madani)… then the CrPC should be changed to say that no man will ever be arrested until and unless he is convicted,” she said.

Justice Katju tried to explain to her that the statements were all police statements and not confessions recorded before a magistrate and hence should not be taken seriously.

He gave up after five minutes as Justice Mishra stuck to her stand and referred the case to the CJI.

Veteran court-watchers said the confusion suggested the court was still grappling with how to deal with issues such as terror.

“There’s much less judicial clarity on how to deal with terror and blast accused,” a senior counsel said. “Human rights or security is a conundrum that can’t be easily resolved.”

This January, the same bench had said no person could be convicted merely because he was associated with a subversive organisation, unless he has shared its unlawful purpose or participated in its unlawful activities.

“There must be clear proof that he specifically intends to accomplish the aims of the organisation by resorting to violence,” the court had said.

This was against the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967, which makes membership per se of a terror outfit a criminal offence.