Nairobi, July 10: Peter Ngari has shuttled between Nairobi and Chennai thrice a year since 2013, spending about Rs 2 lakh on his mother's breast cancer treatment and another Rs 3 lakh on airfare.

Ngari mortgaged his house on the outskirts of the Kenyan capital, sold his car and borrowed heavily from his cousin to raise the amount, equivalent to 800,000 Kenyan shillings.

But last February, the 34-year-old auto parts businessman decided that his medical reliance on India, while his best shot at treatment for his mother, was simply not sustainable.

It was a conclusion that reflected a threat to a key human and economic connection between Africa and India - one that Prime Minister Narendra Modi will try to address at the fag end of his four-nation visit to the continent.

Modi will tomorrow inaugurate a cancer centre at Nairobi's Kenyatta National Hospital, named after Jomo Kenyatta, who led the country after independence in 1963 and is the father of current President Uhuru Kenyatta.

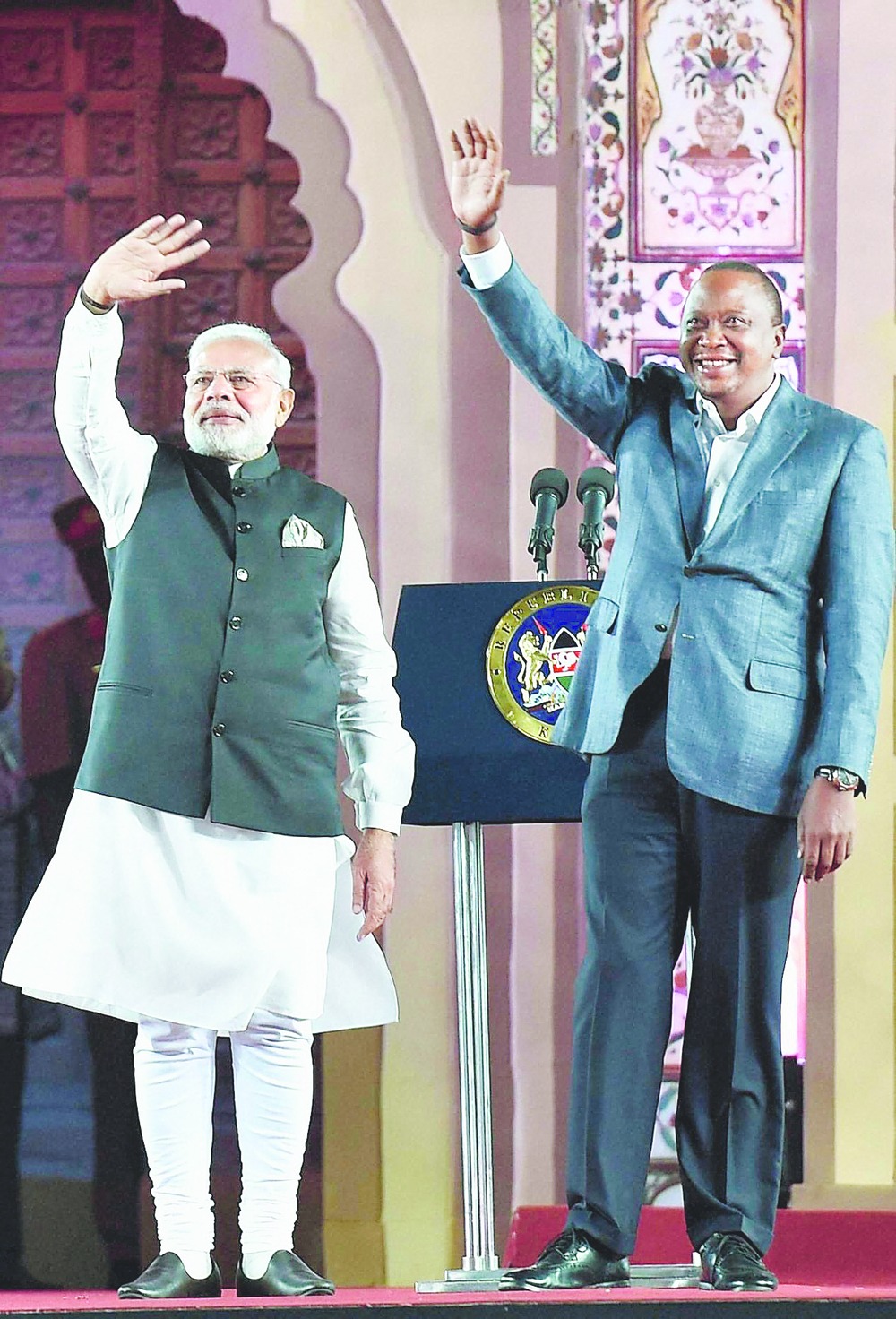

Modi arrived in Nairobi this afternoon from Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, where he spent the morning. He has visited Mozambique and South Africa over the past three days. He will hold formal talks with Kenyatta tomorrow.

India is gifting Kenya the latest version of its Bhabhatron - a telecobalt machine that sends out controlled gamma rays for cancer treatment - designed by the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre, tested by Mumbai's Tata Memorial Hospital and manufactured and developed by a private firm, Panacea Medical.

The cancer centre, Indian officials said, signals a new strategy to provide Indian medical facilities - both government and private-sector - in East Africa to try and retain New Delhi's influence on this region's health-care sector.

For patients like Ngari, this would cut costs by at least half - and by more in cases requiring repeat hospital visits. For the Indian health-care sector, especially private companies, this opens up a larger market of patients who can't afford to travel to India.

"Health care is a crucial area where East Africa and Kenya, in particular, are keen for help from India," Gerrishon Ikiara, economist and foreign policy analyst at the University of Nairobi's Institute for Diplomacy and International Studies, told The Telegraph.

"Whether it's cancer or other chronic diseases, if India can set up at least some treatment facilities here, it will earn dramatic goodwill."

Over 100,000 patients from East Africa - Kenya, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Uganda, Mozambique, Rwanda, Burundi and South Sudan - travel to India each year for treatment at hospitals in New Delhi, Chennai, Bangalore, Mumbai and Calcutta.

From cancer to cataract, the treatment available at Indian hospitals is cheaper compared to the West, and often unavailable in East Africa.

The influx of East African patients has exploded over the past decade and helped fuel a boom in India's medical tourism industry. But it has also triggered deep concerns in the region's countries over the outflow of money.

"For a number of years we have seen patients travelling abroad and spending money that could have been invested in our economy," Kenya's health ministry said in a presentation to the East Africa Healthcare Conference in Nairobi last year.

India had in 2008 tried to set up a Pan-African telemedicine network that allowed patients in African countries to seek advice from doctors at private hospitals in India, such as Apollo or Max.

But the results have been mixed. In countries like South Africa that have a strong broadband network extending to rural areas, the project has witnessed significant success, officials said. But in many other nations, the initiative hasn't had much impact.

The cancer centre at the Kenyatta National Hospital, Indian officials said, would serve as a specialty treatment hub for patients not just from across Kenya but from other East African countries too.

"The idea is to make cancer treatment of the highest quality available here, so that it's more accessible," Animesh, vice-president (sales) for Panacea, who goes by a single name, said.

The private sector health-care industry in India recognises the advantages of investing in East Africa.

Last year, Dr Agarwal's Eye Hospitals, a pan-Indian group of ophthalmology clinics, opened a dozen centres in Africa, including a major one in Kigali, Rwanda, that is attracting patients from neighbouring countries too, Indian and Kenyan officials said.

Others, like Chennai's Apollo Hospitals, Mumbai's Metropolis Health and Hyderabad's Global Hospital, are eyeing investments in Kenya, East Africa's largest economy.

But East Africa needs many more hospitals and clinics offering Indian medical care for the medical relationship to remain sustainable, said Ngari. The cancer centre Modi will inaugurate tomorrow is a good start - but just that, he said.

"We want India to be our doctor," he said. "I hope India wants that too."