Dr Parthasarathi Mukhopadhyay was heading to Washington DC for a weather conference. It was 2016, and India had just rolled out its most advanced weather forecasting system then – a global forecast system with 12-15-kilometre resolution that represented a significant leap forward for the country's meteorological capabilities.

But Mukhopadhyay wasn't satisfied. The scientist had spent his career watching India play catch-up in weather prediction, always a step behind the Americans at NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration), the Europeans at ECMWF (European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts), or the British at the Met Office.

Even that latest Indian system, impressive as it was, relied heavily on the American NOAA’s technology and continuous upgrades from overseas.

Everything changed in 2017, when Mukhopadhyay and his team organized an international conference INTROSPECT at Pune. It was really an introspection for them. German scientist Peter Bechtold was presenting his strategy for reducing grid sizes in weather models – the holy grail of meteorological accuracy that allows predictions to zoom in from broad regional forecasts to hyperlocal precision.

As Bechtold explained the technical intricacies, Mukhopadhyay found himself scribbling notes, his mind racing.

"From that moment, I started to introspect," Mukhopadhyay recalls as he spoke to The Telegraph Online. "I wondered if a similar model could be made integrating Indian data to achieve forecasting for a lower grid size."

The impossible project

What happened next defies conventional wisdom about how breakthrough scientific projects work. There were no government grants, no international partnerships, no technology transfer agreements.

Mukhopadhyay simply gathered a small team of scientists at Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM) Pune and announced they were going to build the world's most accurate weather forecasting system from scratch.

The challenge was staggering. Weather prediction requires processing enormous amounts of atmospheric data through complex mathematical models that simulate the physics of air movement, temperature changes, humidity patterns and pressure systems.

The computational demands are so intense that only the world's most powerful supercomputers can handle the workload. Most countries simply license existing models from weather superpowers like the US.

Mukhopadhyay's team had something else in mind. Working nights and weekends, they began writing codes line by line.

They analysed atmospheric physics equations, studied Indian weather patterns spanning decades and developed algorithms specifically tuned to the subcontinent's meteorological challenges.

The breakthrough came slowly, then all at once. Their model wasn't just working; it was achieving something unprecedented.

While the world's best systems could predict weather accurately down to grids of 12-15 kilometres, their system was hitting 6-kilometre precision. That difference sounds small but represents a revolution in forecasting capability.

"A 12-kilometre grid might tell you it's going to rain in your district," explains Mukhopadhyay. “A 6-kilometre grid can tell you it's going to rain in your village, at what time, and how heavily."

The model is developed mostly by young scientists namely Dr. Siddharth Kumar, Dr. R. Phani Murali Krishna, Dr. Prajeesh, Dr. Medha Deshpande and few others IITM scientists.

In tune with Govt. Of India's initiative to take the country forward with the help of young mind, this milestone achievement will continue to keep India's supremacy in weather forecasting in the globe in years to come.

International shock

When Mukhopadhyay and his team published their findings in Geoscientific Model Development, one of the world's most prestigious meteorological journals, the international reaction was swift and stunning.

"When I sent the paper to my peers across countries, they were at surprise to see how could have we achieved this?," Mukhopadhyay remembers. "They might have wondered how we could possibly pull off something like this from India with limited resources." When I sent the paper across worldwide,

The scepticism was understandable. Here was a team from a developing country, working without the massive resources of the Americans or the Europeans, claiming to have achieved what the world's best-funded meteorological institutions had been struggling toward for years.

International weather agencies began requesting collaboration. Research institutions wanted to understand the methodology. The model that started as one Bengali scientist's obsession was suddenly being recognised as a potential game-changer for global meteorology.

But recognition was one thing; implementation was another challenge entirely.

The supercomputer bottleneck

The first tests on the IITM's existing supercomputer, Pratyush, were promising but painfully slow. Despite Pratyush's respectable 4.0 petaflops of computational power, generating a 10-day weather forecast took 10-12 hours.

For operational weather prediction, where speed can mean the difference between life and death during cyclones or flash floods, such delays were unacceptable.

The solution came in the form of Arka, a computational monster that Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurated at the IITM on September 26, 2024. With 11.77 petaflops of computational capacity and 33 petabytes of storage, Arka represented a quantum leap in India's supercomputing capabilities.

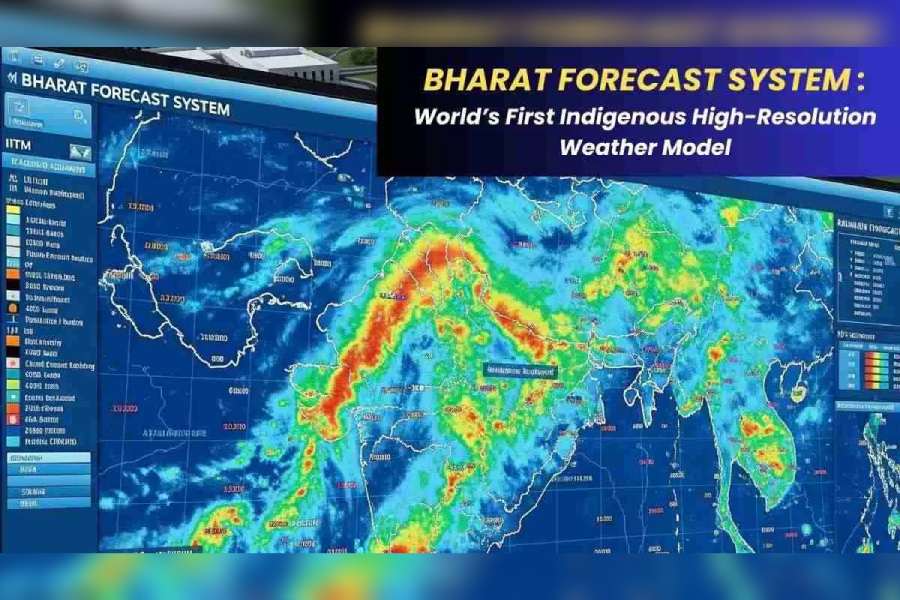

The transformation was immediate and dramatic. The same 10-day forecast that took Pratyush half a day to process was completed by Arka in just three hours. Suddenly, the Bharat Forecast System (BFS) wasn't just the world's most accurate weather prediction model – it was also fast enough for real-world deployment.

Beyond borders

The BFS impact extends far beyond India's boundaries. The system provides high-resolution forecasts for the entire tropical belt from 30° South to 30° North, covering vast swathes of Africa, South East Asia, and South Asia – regions where accurate weather prediction can prevent humanitarian disasters.

This global reach gives India unprecedented soft power in international climate discussions. Countries that once looked to American or European weather agencies are now turning to Indian expertise.

Within India, the implications are revolutionary. The system integrates with a rapidly expanding network of doppler weather radars – currently 40 operational units with plans to reach 100 – creating a comprehensive early warning system that can predict weather events down to the panchayat level.

For farmers, this means rainfall predictions specific to their fields, allowing precise decisions about planting, harvesting, and irrigation.

For urban planners, it means advance warning of heatwaves, storms and flooding with neighborhood-level precision. For disaster management authorities, it means the ability to evacuate specific areas hours or even days before dangerous weather arrives.

Jitendra Singh, Union minister of earth sciences, has called the BFS an “indigenous breakthrough” that “positions India among the global leaders in weather prediction… It is a proud testament to the country’s growing self-reliance in science and technology.”

The open source philosophy

Mukhopadhyay chose to make the entire BFS model open source – freely available to researchers and meteorological agencies worldwide.

This decision reflects a philosophy that scientific breakthroughs should benefit humanity broadly, not just the countries that develop them.

"I believe that in the future, this model will be improved significantly," Mukhopadhyay explains. "This can help us generate more accurate hyperlocal predictions and successfully predict events like flash floods and cloud bursts."

The open source approach has already begun paying dividends. International researchers are contributing improvements to the model, creating a global collaborative network centered around Indian innovation.

It's a complete reversal of the traditional dynamic where India imported foreign scientific expertise.

The BFS success story is part of a broader transformation in India's scientific capabilities. The Union ministry of earth sciences has invested heavily in indigenous supercomputing infrastructure, with Arka in Pune complemented by the Arunika cluster in Noida, which focuses on marine ecosystems and disaster preparedness.

Both systems were developed in partnership with AMD but represent fundamentally Indian projects – designed, built, and operated according to Indian priorities and specifications. The days of depending entirely on foreign weather models and imported predictions are ending.

For Mukhopadhyay, now retired but still involved in refining the system, the success feels both satisfying and natural. "It comes from a scientist's mind that looked for solving a problem for society in a holistic way," he reflects.

The broader implications are profound. As climate change makes weather increasingly unpredictable and extreme, the countries with the best forecasting capabilities will have significant advantages in protecting their populations and economies.

India, thanks largely to one Bengali scientist's refusal to accept second-best, has positioned itself at the front of that technological race.