Manoranjan Byapari has returned to Calcutta after having attended the Jaipur Literature Festival. There, the story of this Bengali Dalit writer's life's journey - as narrated in the session titled Interrogating the Margins - made quite an impression on the gathered audience.

Byapari lives in Khudirabad on the outskirts of Calcutta, where he and a colleague cook mid-day meals for students of the Helen Keller Badhir Vidyalaya for the deaf and the blind, every day. He is perhaps the only rickshaw-puller-turned cook to have his works published by Oxford University Press. He has authored about a dozen novels and over a hundred short stories and some works of non-fiction in Bengali.

Is it true that impressed by his fiery speech in Jaipur, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) asked him to join its ranks? The former Naxalite is livid at the mention. He thunders, "I know my enemies are spreading these canards."

According to Byapari, after his session, a group of swayamsevaks and possibly one sarsanghchalak - he is not sure - had approached him. He had spoken at length about how Dalits have been exploited for thousands of years in the name of karma phal or bad karma. The thrust of Byapari's argument was that there is no God, no religion, no castes, and it is time to change some rigid societal beliefs.

The RSS volunteers, apparently, interrogated him about his "reactionary arguments". "They told me that the caste system in Hindu-ism is a thing of the past. At least, it was something they didn't believe in. But when I asked them to explain how Namasudras like myself were still discriminated against, they didn't have any answers."

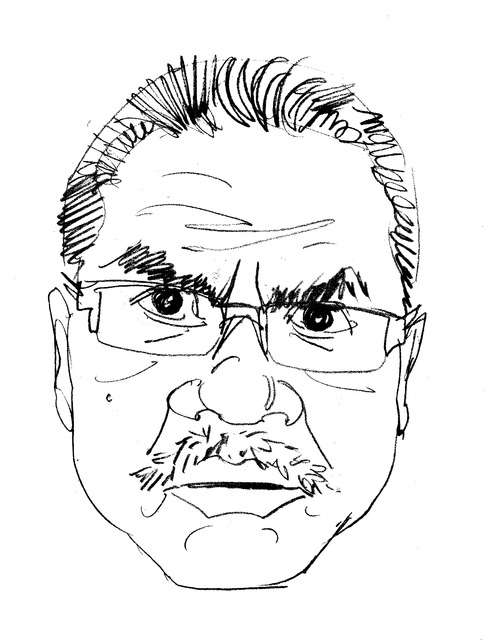

Ibumped into Byapari at the conference, Dalit Literature in Bengal, organised at Presidency University, Calcutta. Though I had read some of his works, I had no idea what he looked like.

A man carrying a jhola full of books took a seat next to mine in the auditorium. Waiting and with little else to do, I was casting furtive glances at his books when a voice said, "The name's Byapari. I have no shame in peddling my own books." So saying he pointed to a slim volume and said, "It's been selling quite well."

I was familiar with the book in question, Interrogating My Chandal Life, the English translation of the memoir, Itibritte Chandal Jibon. Chandal is a Sanskrit word for someone who deals with the disposal of corpses and is considered untouchable. In current times, it has also been used as an omnibus term to connote Scheduled Castes.

For some reason I had the impression that the writer would be a frail withered old man, exhausted from life's struggles. The man in front of me was anything but.

Byapari has a stocky frame. His broad wrists open up into rough, calloused palms. When I enquire about his age, he replies, "Most probably I will turn 68 this summer, give or take a few years. I belong to a people whose births were never recorded. All that my mother remembered to tell me was that there was a raging Kalbaisakhi the day I was born in the marshes of Barisal [now in Bangladesh], a few years after Partition."

We shake hands. And that's when I become aware of the rings on his hand. Four of them inscribed with the Bengali letters Ji Ji Bi Sha. Byapari tells me how one day he was ferrying a woman passenger in south Calcutta's Jadavpur area, when he suddenly asked aloud the meaning of the words. "Jijibisha means the will to live," she replied and then asked Byapari where he had come across it. When Byapari said he had read it in a book, the woman wanted to know how he'd learnt to read and how far he had studied. Thereafter, impressed, she asked him if he would like to write a piece for a magazine. Before getting off, she scribbled her name and address on a piece of paper. It read: Mahasweta Devi.

Coincidentally, Byapari had been reading her book, Agnigarbha. The book was under the very rickshaw seat that had been her perch. Byapari eventually wrote a piece titled, I Drive a Rickshaw. It was published in Bartika, a magazine published by Devi.

Describing this providential encounter with the late writer and activist, Byapari wrote: "The wheels turned and we moved closer to our destination. But which wheels were really turning? The rickshaw wheels or the wheels of my destiny?"

Byapari is proud of the fact that he is largely a self-taught man. Has never been to school. Was thrown into jail in the early 1970s when Naxalism was at its peak. "I consider the jail as my university. I'd have remained illiterate if I had not been imprisoned," he says. He had apparently learnt to write with a stick on the dirty prison floor when he was 20.

He taps on one of the books in his hand and says, "You can read it here." Batasey Baruder Gondho or The Smell of Gunpowder is about his time in jail, as well as the turbulent days of Naxalism in Bengal. "This one is being tran-slated into English [titled Jailbreak] and they might turn it into a movie too," he says. When I ask him if it's going to be a Bollywood movie, he turns all enigmatic on me. Later, however, scrolling through his Facebook timeline, I come across a picture of him chatting with director Anurag Kashyap.

In the photograph, Byapari is seen wearing a gamchha. At Presidency too, the poor man's chequered scarf lay coiled around his neck, like a sleeping viper. It makes a statement all right, beyond fashion.

"It is handy," says Byapari. And adds, "You can use it to wipe off the sweat after a hard day's work. You can spread it on the ground - no matter if you are at a railway platform or a footpath corner - and sleep or tie it on the head like a turban or tie a piece of brick in it and aim for an adversary, when attacked."

The gamchha has been Byapari's constant companion right through his boyhood days in the refugee camps of interior Bankura in Bengal to Dandak-aranya in Odisha, to the iron mines of Chhattisgarh's Dalli Rajhara, and of course, railway platforms across the country. He shows me a picture of himself stirring a huge ladle in a large pan with the gamchha tied at the waist. "It is still my best friend."

Our exchange, pre-conference and in between sessions, is much interrupted, fractured in places, but enough to give us a sense of the man. He is passionate about a number of issues - Dalits and their grinding poverty, Dalits and their burning hunger, the apathy of upper-caste writers to their problems, how Brahminism devoured Buddhism in India - but he is most animated when we talk about Communists and how they did nothing for Dalits.

Says Byapari, "Communists lost their ground in India because they go by books and theories scripted abroad. Since Marx, Lenin or Mao never spoke about India's caste system, Communists in India worry about class struggles, but ignore the bitter reality of Dalits," he says. He doesn't spare the Naxalites either. "How can you even coin an expression like Chiner chairman amader chairman... Communist China's chairman is our chairman," asks the angry old man referring to a slogan used by Naxalites in the 1970s.

He feels the time has come for a new and inclusive narrative for Communists in India, especially one in which Dalits, Adivasis, Muslims and even members of the third sex will be included. He says, "Just like a movement spearheaded by the late Shankar Guha Niyogi [the founder of the Chhattisgarh Mukti Morcha, a trade union in central India]. Niyogi ji had mixed ideologies of Marx, Gandhi, Lohia and Ambedkar, which can be a unique formula for next generation Communists."

The firebrand writer has just turned from prose to poetry. In a recent attempt, he writes: My pen is not that which bows before the Brahmins/Or prays for respite from those whose hands are still bloody from Marichjhapi deaths/My pen is mine/Sharp like that arrow which knows no stopping till it finds its target.