An air of petulance and a strongly rumoured threat of resignation hung over Mint Street as a row between the finance ministry and the Reserve Bank of India over the boundaries of the central bank’s independence spooked markets early in the day until the Centre issued a statement affirming its faith in the autonomy of the RBI.

Stocks and bonds fell and the rupee tumbled amid reports that RBI governor Urjit Patel was mulling his resignation after media reports suggested that the government had sent out three notices to the central bank threatening to invoke section 7 (1) of the RBI Act.

The section empowers the government to direct the RBI to adopt certain measures on issues of public interest, overriding the latter’s reservations.

“Both the government and the central bank, in their functioning, have to be guided by public interest and the requirements of the Indian economy. For the purpose, extensive consultations on several issues take place between the government and the RBI from time to time…. The government, through these consultations, places its assessment on issues and suggests possible solutions. The government will continue to do so,” the finance ministry said in a statement that did not refer to its Section 7 directives.

“The autonomy of the central bank, within the framework of the RBI Act, is an essential and accepted governance requirement. The Government of India has nurtured and respected this,” the statement added.

The statement was seen as a climbdown by the government after its aggressive posturing in the past few weeks when disagreements between the RBI and the finance ministry escalated. At an evening media conference, finance minister Arun Jaitley said he did not have anything more to say beyond his ministry’s statement on the RBI issue.

However, the RSS-backed Swadeshi Jagran Manch, whose associate S. Gurumurthy joined the RBI board when Jaitley was on sick leave, did not pull any punches. “The RBI should work in sync with the government or otherwise resign,” the Manch’s co-convener Ashwani Mahajan told PTI.

The threat of Patel’s resignation had gained some credence after RBI deputy governor Viral Acharya in a speech delivered on October 26 had attempted to draw an analogy between the circumstances that have engulfed the RBI with the situation that erupted in Argentina in January 2010.

Then, Argentina’s central bank chairman Martin Redrado had resigned in protest against interference by the Cristina Fernandez government’s interference in the central bank’s decisions. “My time at the central bank is up and that is why I have decided to leave my post… We have arrived at this situation because of the national government’s permanent trampling of institutions,” Redrado had then said.

The sensex, which had plunged 846 points from Tuesday’s close to 33,596 points just after 10 am, clawed back to 34,442 points, registering a gain of 550 points at the close, buoyed by the government’s statement which had triggered a wave of buying by state-owned financial institutions.

Investors had turned jittery because section 7 of the RBI Act, which has never been invoked in the past.

Sources said three notices had gone to the RBI – all of which referred to section 7 (1) of the RBI Act. The last letter went out on October 10.

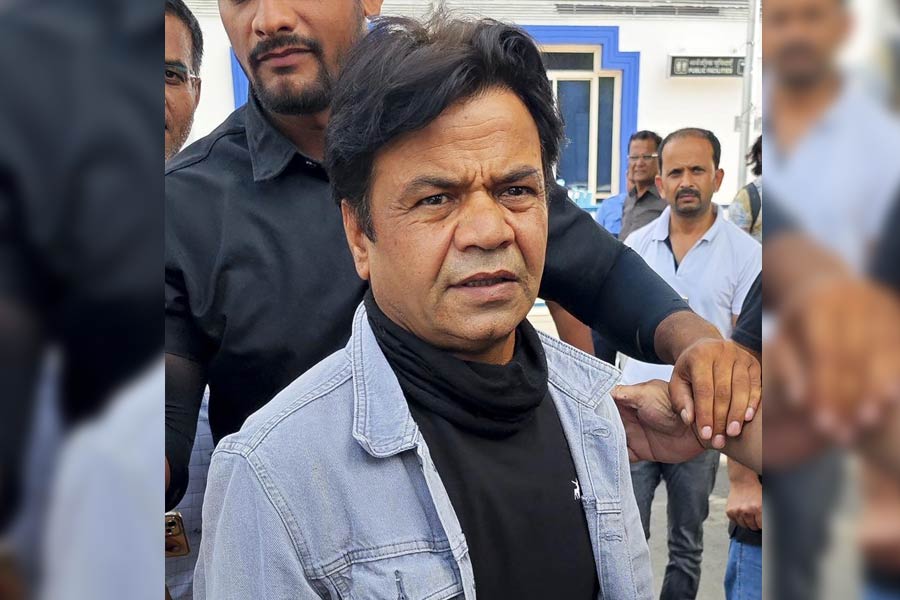

Arun Jaitley Sourced by The Telegraph

They were emphatic that there was no reference in these notices to the more draconian section 7 (2) of the Act which allows the Centre to entrust the superintendence of the affairs of the RBI and its decision-making process to its 21-member central board of directors. Such a step would have turned Patel into a lame-duck governor.

“If, as reported, the government has invoked section 7 of the RBI Act and issued unprecedented ‘directions’ to the RBI, I am afraid there will be more bad news today,” former finance minister P. Chidambaram had tweeted in the morning.

M. Govinda Rao, a member of the Prime Minister’s economic advisory committee when Manmohan Singh was in charge, said: “They (the finance ministry) are behaving like headless chicken… the controversy was unnecessary.

The talk of invoking section 7 had first arisen in August when the government was trying to nudge the RBI to relax debt default recognition norms in the case of troubled power plants run by the Adanis, the Essar group and the Tatas.

At that time, economic affairs secretary S.C. Garg had said that a panel headed by the cabinet secretary would take a call on whether or not to invoke section 7 in order to resolve the crisis in the power sector.

But there were two other issues on which the government and the RBI had serious disagreements: the move to relax lending restrictions on 11 state-owned banks that had run up a huge stack of bad loans that severely strained their capital requirements, and its attempts to force the central bank to transfer a part of its reserves to the government, which was a clear throwback to the Redrado episode. The Argentine government had tried to force its central bank to transfer $ 6.6 billion to the national treasury.

Finally, the government has been trying to persuade the RBI to ramp up credit flows to medium and small businesses in the country who represent a very vocal vote bank of the BJP-led government.

The next meeting of the RBI’s central board of directors will be held on November 19 where all of the contentious issues are expected to be discussed.

“We have talked to each other but have not invoked Section 7 at any stage and, as far as I know, will be very reluctant to do so,” said a top finance ministry official involved in talks with the RBI.

”What the government wants to do is to roll over credit given to businesses. This is bad banking and a sure-fire recipe for disaster,” said Rao.

“The finance ministry’s statement is ambiguous and does not fully clarify the issues at hand,” said A. Prasanna, Chief Economist at ICICI Securities. “Still it does sound like the finance ministry is trying to dial down the temperature.”

Martin Redrado Sourced by The Telegraph

- THE REDRADO PARALLEL

The following is an extract from RBI deputy governor Viral Acharya’s speech of October 26, 2018. The Argentine episode mentioned below sets the backdrop for the crisis that has engulfed the RBI which is battling similar attempts by the finance ministry to circumscribe the autonomy of India’s central bank.

Acharya’s use of the Redrado analogy appeared to lend some credence to rumours of Urjit Patel’s threat of resignation that swirled around Mint Street on Wednesday.

This is how Acharya prefaced his speech:

No analogy is perfect; yet, analogies help convey things better. At times, a straw man has to be set up to make succinctly a practical or even an academic point. Occasionally, however, real life examples come along beautifully to make a communicator’s work easier. Let me start today with an antecedent from 2010 as it is particularly apposite for the theme of my talk.

“My time at the central bank is up and that is why I have decided to leave my post definitively, with the satisfaction of my duty fulfilled,” Mr Martin Redrado, Argentina’s central bank chief, told a news conference late on Friday, January 29, 2010.

“We have arrived at this situation because of the national government’s permanent trampling of institutions,” he said. “Basically, I am defending two main concepts: the independence of the central bank in our decision-making process and that the reserves should be used for monetary and financial stability.”

The roots of this dramatic exit lay in an emergency decree passed by the Argentine government led by Cristina Fernandéz on December 14, 2010, that would set up a Bicentennial Stability and Reduced Indebtedness Fund to finance public debt maturing that year. This involved the transfer of $6.6 billion of the central bank reserves to the national treasury. The claim was that the central bank had $18 billion in “excess reserves”. In fact, Mr Redrado had refused to transfer the funds; so the government attempted to fire him, by another emergency decree on January 7, 2010, for misconduct and dereliction of duty; this attempt, however, failed, as it was unconstitutional.

Besides sparking off one of the worst constitutional crises in Argentina since its economic meltdown in 2001, the chain of events led to a grave reassessment of its sovereign risk.

Within a month of Mr Redrado’s resignation, Argentine sovereign bond yields and the annual premium cost for buying insurance against loss from default on Argentine government bonds (measured as the sovereign credit default swap spread) shot up by about 2.5 per cent or 250 basis points, by more than a fourth of their prior levels.

Alberto Ramos, Argentina analyst at Goldman Sachs, noted on February 7, 2010: “Using central bank reserves to pay government obligations is not a positive development and the concept of excess reserves is certainly open to debate.

It weakens the balance sheet of the central bank and provides the wrong incentive to the government, as it weakens the incentive to control the rapid expansion of spending and to promote some consolidation of fiscal accounts in 2010.”