Matinee idol Arindam Mukherjee is getting ready. As he converses about the (rather dismal) box-office status of his new film, Subrata Mitra’s camerawork pans on his shoe as he ties its laces.

As Arindam continues, he is informed that the film, in its second week amid the last few days of the month, isn’t pulling the crowds in.

“Aagey toh ei shob kotha shunte hoyni,” he says. “Achchha, chhobi ta teh ki achhey, tui chhara?” he is asked. He looks up, the camera lingering on his handsome face, and says in a matter-of-fact manner: “Aami toh achhi, isn’t that enough?”

That, clearly, was enough for Nayak. Enough even now, almost 60 years after it first flickered on the big screen and became part of cinema history. The Satyajit Ray classic, which had “Mahanayak” Uttam Kumar playing a version of himself but in a way that only he could, continues to be a trailblazer even in its re-release run.

At a time when new films — and that includes a lot of Hindi cinema — are struggling to stay afloat after the first few days of release, Nayak entered its third week on Friday. The restored 4K version of the film, which brings alive its moods and moments, its shades and nuances in the way Ray had envisaged, has drawn viewers in hordes to theatres across the country.

That includes cinephiles of all ages, some looking to relive the nostalgia of having watched it in the cinema many decades ago, while many who have seen it in a rather grainy form on the small screen are queuing up to experience it on the big screen.

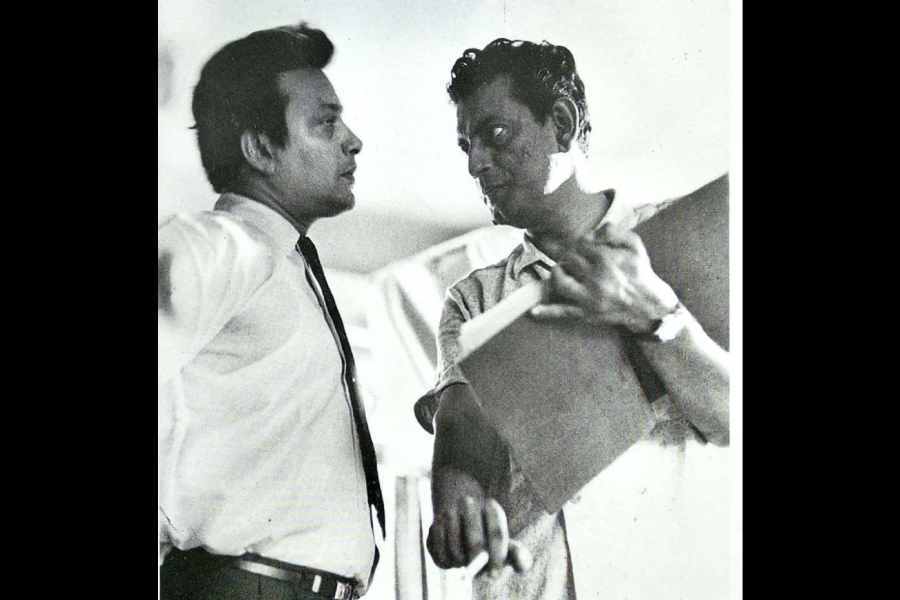

A scene from 'Nayak'

Since February 21, when it released not only in Calcutta but in other major cities across the country — Delhi to Mumbai, Pune to Bengaluru, Chennai to Hyderabad — Nayak has been a phenomenon that continues to grow.

“There was a huge buzz surrounding the re-release of Nayak and the response has been nothing short of phenomenal. Besides houseful shows in Calcutta, we have had full houses in Delhi and Mumbai and even in cities like Hyderabad and Chennai, which has been both a pleasant and a reassuring surprise,” Varsha Bansal of RDB and Co, whose grandfather R.D. Bansal produced Nayak and five other Ray classics, told The Telegraph.

Varsha has not only worked tirelessly to restore these six films — which include Mahanagar, Charulata and Joy Baba Felunath — but has taken them across the world, to countries that include Slovenia, Albania and Saudi Arabia, to widespread acclaim and great success.

In its second coming on Indian screens, the success of Nayak has prompted the addition of new shows at many centres. The demand for the film has even invited the addition of new cinemas, including Nandan.

“We are thrilled to have re-released Nayak at PVR-INOX. Even six decades later, Nayak remains remarkably relevant,” Niharika Bijli, lead strategist, PVR-INOX, told this newspaper.

“The response has been overwhelming, not just in Calcutta but also in Delhi-NCR, Mumbai and Bengaluru. It is heartening to see audiences who first watched the film decades ago returning with their families, proving cinema’s power to transcend generations.”

Debashish Chakraborty, manager of Cinepolis Lake Mall, where the film is in its third week, said: “Nayak has attracted a wide range of admits on its re-release because of the restored picture quality and the English subtitles.”

Chakraborty said a large number of young viewers have been coming to watch the film.

Naveen Chokhani, the proprietor of Navina Cinema on Prince Anwar Shah Road, is ecstatic that elderly audiences, apart from the youth, have walked in to watch Nayak.

“That they have made the effort to come out and watch an Uttam Kumar and Satyajit Ray masterpiece several decades after they would have possibly watched it on the big screen is heartwarming,” said Chokhani.

Nayak’s success has made Chokhani and others this newspaper spoke to confident that the audiences would lap up the re-release of many other Bangla classics, much like it has happened in Bollywood.

The re-release of Nayak, which touches upon both the towering personality and the slowly unraveling vulnerability of a film star as he speaks to a young journalist (played by Sharmila Tagore) on atrain ride from Calcutta to Delhi, has found support also from filmmakers like Shoojit Sircar, Dibakar Banerjee and Suman Ghosh.

“Reviving a classic is an absolute delight for cinephiles as it not only allows us to revisit and re-appreciate cinematic masterpieces but also underscores the timelessness and enduring relevance of these works,” Sircar had told this newspaper before the re-release of Nayak.

Tagore, who watched the film in Delhi in its first week, is ecstatic with the technical superiority of the big-screen re-release.

“It was a treat to watch Nayak, it was a wonderful experience. The big screen makes such a huge difference,” Ray’s favourite leading lady said.

Pinaki De, committee member of the Satyajit Ray Society, has watched the re-released Nayak twice already and plans a re-watch at Nandan this weekend. Others like Sayandeb Chowdhury have “rediscovered” the film and many of its aspects.

“As one who has researched Uttam Kumar’s cinema extensively and seen Nayak umpteen times, I was no doubt excited about the re-release but I was not prepared for the extent to which I ended up rediscovering the film on the big screen, thanks to the newly digitised print,” said Chowdhury, the author of Uttam Kumar, A Life in Cinema.

“The suppleness of Subrata Mitra’s camerawork, the detailing of Bansi Chandragupta’s design, and the intensity of Uttam Kumar’s eyes left me enchanted. I saw it in Chennai on the first weekend and was chuffed to see a robust attendance, many of whom were not from the Bengali diaspora there.”

Filmmaker Atanu Ghosh expressed the same sentiment. “The lustre of the restored print brings out Uttam Kumar’s boils and bumps since he was not wearing make-up. And that is obviously metaphorical, representing the gilded mask of stardom being stripped away, exposing the fragile soul below,” he said.

“The shadows stretch in monochrome frames, looking brilliantly poignant now; the gray tones, particularly in the dreams, so richly evocative, getting back their original tone. Ray’s gaze is tender yet unrelenting, his storytelling quiet but unsettling, and the film still seems contemporary and universal after 59 years.

“It’s no wonder the audiences are lapping it up emotionally and appreciatively, particularly the film buffs of the new generation, and that is the biggest reward for all of us.”

Sanghamitra Chakraborty, author of Soumitra Chatterjee and his World, said: “The audience in the theatre responded with gentle laughter to the astute humour throughout the film but slipped into a sombre silence as the hero unravelled. And then, as the frame froze on the Nayak — sunglasses, garland, mobbed by fans — in the end, there was a standing ovation.”

Varsha Bansal of RDB and Co said Sandip Ray, filmmaker and Satyajit Ray’s son, had provided “huge support” towards the re-release of Nayak.

Contacted by this newspaper, actor Gourab Chatterjee, Uttam Kumar’s grandson, expressed his happiness at the reception Nayak has received.

“The re-release has been a huge hit. I had the opportunity to watch it earlier on the big screen, along with a few of my grandfather’s earlier films, on his birth and death anniversaries but I would like to watch it in the theatre again,” he said.

RDB and Co, which also re-released Ray’s Mahanagar last year, has been so enthused by the success of Nayak that they are planning to give Joy Baba Felunath a big-screen re-run. “We are now certain that there is an audience, of all ages and across the country, for these classics,” Varsha said.