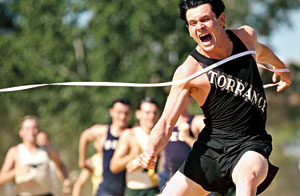

Angelina Jolie opens Unbroken with a shot of a celestial blue sky that soon darkens with a battle scene so tense and fluidly choreographed that you quickly sense that, as a director, she leans closer to hell than heaven. She has given herself plenty to work with: The movie takes a slice out of the life of Louis Zamperini, the Olympic runner turned World War II bombardier who, after surviving a plane crash and 47 days adrift on the Pacific, was fished out of the water by a Japanese patrol boat and then imprisoned in camps where he was brutalised for years. His is one of those stories that has come to define the Greatest Generation.

That story, in its human reach and cosmic scale, in its different permutations and theatres of war, has been recounted in memoirs, novels, fiction films and all too painfully true documentaries. It emerges again in Laura Hillenbrand’s 2010 best seller, Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience and Redemption, which is the basis for the movie. With some narrative rejigging, a lot of compression and one significant exception, Jolie follows the lead of the book, which focuses on the first 25 years or so of Zamperini’s life. She also sweeps through his early education as a peewee gangster, truculent son of Italian immigrants and accidental athlete who discovers he can run like the wind, but she gets to the war sooner.

UNBROKEN (U/A)

Director: Angelina Jolie

Cast: Jack O’Connell, Domhnall Gleeson, Miyavi, Garrett Hedlund, Finn Wittrock, Jai Courtney

Running time: 137 minutes

Jolie is a fast worker. After her inaugural nod at the wide blue yonder, she thrusts you inside the claustrophobic confines of a B-24 bomber that’s soon under Japanese attack. There, the adult Louie, as he was called, bounces through the plane while bullets begin shredding its exterior and soon its occupants, the fusillade opening little circles of light in the hull as effortlessly as a pencil punches holes in paper. It’s a shrewd opener, because it immediately puts you on notice in regard to the story’s life-and-death stakes and draws you close to Louie (the appealing Jack O’Connell). Zamperini was a distance runner, but here he’s a sprinter whose quicksilver movements — he crouches and scuttles while tending the wounded plane and men — suck you in with gravitational force.

Louie’s life moves so rapidly here that about 30 minutes after the movie’s start, he’s running laps at the 1936 Berlin Olympics. There, he catches a glimpse of Jesse Owens and gawps at the cheering crowds and bloated Nazi spectacle, which Jolie conveys with digital effects and a touch of Leni Riefenstahl pomp-and-creepiness. Then Louie’s off to the races, and we’re off to something of a narrative cheat. He scores mightily on the track — with a rabbity final sprint — but Jolie pumps the inspirational uplift so high that with all the soaring music, swirling camerawork, excited commentary and slow-motion shots of Louie’s straining and gasping you may not realise he didn’t win any Olympic medals.

That Zamperini didn’t win that day doesn’t lessen his accomplishments on or off the track, of course, or make his story any less touching. Being an Olympian is a triumph in and of itself, yet that truism doesn’t seem to have been grand enough for Jolie’s purposes. The Olympic interlude is sandwiched between some wartime scenes, right after the plane that Louie’s on starts to malfunction and just before it falls into the Pacific. The placement of his Olympic experience suggests that Louie’s life is flashing before him or that he’s drawing strength from a memory. But the triumphalism of the race is so excessive that it competes with, rather than complements, the war scenes and ends up being another clip in what increasingly will feel like one man’s extended highlight reel.

It took four marquee writers — Joel Coen, Ethan Coen, Richard LaGravenese and William Nicholson — to wrestle Hillenbrand’s many pages into a movie, which clocks in at two hours 17 minutes. That’s scarcely enough time for any life, but it’s impossible when each chapter in that life could itself be a book (including an underplayed epiphany), and the strain shows, especially in the camp sequences. Jolie does fine work throughout, including on the raft where, after the crash, Louie and two others, Phil (Domhnall Gleeson) and Mac (Finn Wittrock), battle dehydration, starvation and sharks, including one that the men, in a jolting scene, wrestle onboard and devour. Like a lot of actors turned directors, she’s good with the performers, even when platitudes gush from their mouths along with the blood.

That blood gushes and splatters, mostly discreetly, at times with misplaced tastefulness, as Louie falls and rises in spirit and body. Jolie’s tendency to go David Lean with this material works against her in the camp sequences, because what you want to know isn’t what the prisoners looked like standing in formation in long shot but what they thought and did to survive. What the movie ends up in desperate need of is a sense of life made real and palpable through dreadful, transporting details, not a life embalmed in hagiographic awe. You can find that movie here, at times, tucked amid the crane shots and angelic singing, though mostly in the perverse intimacy that emerges between Louie and the sadistic officer, Watanabe (Miyavi), and shows just how personal war can really be.

Manohla Dargis

(The New York Times News Service)

Is Angelina Jolie a better director or actor? Tell t2@abp.in