It’s a vision straight out of the theatre of the absurd. A swanky mall stocked with every imaginable international brand smack in the middle of nowhere. A future township of gated condominiums waiting to be peopled by Mercedes-driving, Louis Vuitton-flaunting, Adidas-sporting cheerleaders of a shining India, as the site for a climactic encounter where a Brahmin ‘fugitive’ holds a low-caste police officer hostage. Only minutes before, the Brahmin had humiliated the policeman (if it were his own village, he says, he would have peeled the skin off the latter’s back for his temerity in rising above his station). Now, he uses the officer as a human shield – all the ignominy of pollution by contact forgotten – against a posse of policemen who watch helplessly. Minutes later, even as the officer facilitates his escape, the Brahmin mouths another filthy epithet at his caste.

In a wicked reference that somehow escaped the censors who mandated 13 cuts to the film, the township is called ‘Lotus’ Oasis, just in case anyone missed the flower. Incredible India, a photographer journalist had mockingly commented earlier in the film. Surreal India would fit just as well.

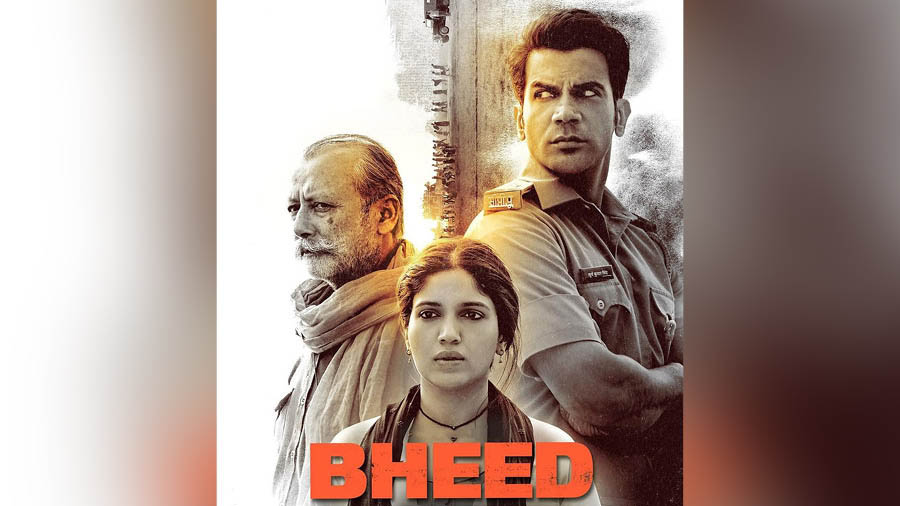

Over the course of his films, Anubhav Sinha has cast a not very flattering eye on India as a nation. In Bheed, the catastrophe that fell migrant workers in the wake of the lockdown foisted arbitrarily on the nation provides the backdrop to expose our utter failure as a society. If Mulk, Article 15 and Thappad, a trilogy of sorts, address our petty-mindedness as a people when it comes to religion, caste and gender respectively, Bheed incorporates all these concerns in a cauldron that is forever on the boil. We are not, as the filmmaker underlines, a society. We are a horde. A journalist in the film likens us to a truckload of goods precariously held together by ropes; it would take just a minor bump in the road for the ropes to come apart and the bundle to unravel. It has been unravelling for years now, and Covid-19 provided only the final cut to show us up as a people. The government’s high-handedness and cluelessness only aggravated and brought the intrinsic ugliness in us out in the open.

The director is relentless in hammering unpalatable home truths

A police check-post in the back of beyond becomes a microcosm of a nation coming apart at the seams. As the lockdown comes into effect, people flee from all corners of each state, making their way ‘home’. The irony of it is that India, the country, is no longer home. Each state – no particular state is named in the film – has created its own boundaries that are being brutally and zealously guarded against ‘infiltrators’. Citizens have overnight become refugees in their own country.

We have of course always been a ‘divided’ nation, and the filmmaker highlights these divisions through the characters. Police officer Surya Kumar (Rajkummar Rao, spellbinding), who hides his caste name ‘Tikas’, but cannot overcome centuries of oppression that have robbed him of his vitality. Other officers like Yadav (Ashutosh Rana) and Ram Singh (Aditya Srivastav) – both brilliant – provide a pungent picture of a caste-ridden society.

At the other end of the caste spectrum is Dr Renu Sharma (Bhumi Pednekar), in a relationship with Tikas, which could spell disaster for him. In a telling lovemaking sequence, he fails to ‘perform’ and articulates how caste comes into the picture even in a moment of such intimacy. And Balram Trivedi (Pankaj Kapur, another terrific turn in the film), the Brahmin security guard robbed of all his ancestral privileges and yet holding on to his pride which not only prevents him from accepting food from Muslims but also has him flinching from the touch of Ram Singh (in a sequence that would be hilarious if it were not so tragic, the Brahmin threatens to put a curse on Singh for touching him!). There’s also the rich woman in the SUV (Dia Mirza), who opines how ‘yeh log’ (the marginalised) never have issues of lactose intolerance or migraine.

The director is relentless in hammering unpalatable home truths about how we survive as a nation despite ourselves. As Surya says, ‘We only seem to have Shuklas, Singhs and Trivedis here.’ The film made me flinch at several points, uncomfortably pointing out to me my own privileges, which is more than what I can say about any Hindi film in recent memory. Menstruating women forced to use newspapers in the absence of sanitary pads. A man (a Brahmin to boot) branded as a Naxal only because he asks for food and is willing to resort to violence to get it. A concrete mixer from whose bowels emerge men and women trying to make a getaway. How were they breathing, someone asks – and I was tempted to use the slogan bandied about in last week’s film, again dealing with aspects of the lockdown, Nandita Das’s Zwigato: ‘Mazdoor hai isliye majboor hai’. This film does not have to use the slogan, it says it all without overstating its case. A low-caste boy beaten to pulp by the village pradhan for daring to drink water from a temple pump. And the unstated, understated irony of other such characters and their interactions.

Censoring the film almost robs it of its vigour

Bheed is an important film. Few Hindi films have the intelligence and honesty to depict reality like it does. Few Hindi films would have the nerve — particularly given the current dispensation where no dissent or narrative that is unflattering to the powers-that-be is allowed — to talk about caste, religion, governance and administration as openly as this one. Few Hindi films would go all out to antagonise every section of society as culpable. Yes, what the migrants faced owed itself to gross administrative and political callousness, and yet, even in the middle of a tragedy of such humongous proportions, we remained a nation of Brahmins and Chamars, Muslims and Hindus, fighting not the government for our rights, but ourselves for petty privileges.

Bheed is also a brave film. And in that might also lie its one weakness. For one, the film might just be judged only for the director’s courage. There are passages in the film that appear rather simplistic. The issues at stake are far too complicated for the kind of pigeonholing we see here. The character played by Dia Mirza, for example, comes across as a caricature more than anything else. I have seen close friends, equally privileged, whose sense of entitlement and lack of concern came couched in more insidious terms. The TV journalists too don’t resonate as authentic. The resolution appears too pat, almost a hat-tip to our famed spirit and resilience.

Also, the theatrical cut belies the expectations of Bheed’s first teaser-trailer. That owes itself to the censoring the film was subject, including two aspects that almost rob it of its vigour. For one, once the paralleling of the lockdown migration to that of the partition is excised, there exists little reason for the film to be in black and white. Two, the power of the one announcement that led to the human disaster, the prime minister’s address to the nation on March 24, 2020, which gave India’s 140-crore population four hours to fend for itself. Censoring that deprives the film of its context. There were more such cuts and one can sense that the final film is shorn of specificity. It becomes a generic account of a ‘natural’ calamity and its ramifications on people at the grassroots, and not how it was a disaster brought about by decisions emanating from the top levels of the government with no concern for its people.

Above all, the biggest challenge Anubhav Sinha faces in Bheed is that the pandemic is too fresh in our minds. The images have played out in front of us and are imprinted in our consciousness. He is up against the very real nightmarish memories of the time, and I wonder if anything we see on screen, despite all its potency, will ever rival what we experienced.

That said, it is important to record our history, even if it shows us in a poor light, and Bheed does that only too well. The film begins with Bob Marley’s quote, ‘If you know your history…’ It could well have ended with George Santayana’s/Winston Churchill’s take on people who don’t learn from ‘the past/history’, being condemned to repeat it. We as a nation failed to learn from Lockdown 1, and the second wave a year later witnessed a more calamitous one. We haven’t learnt yet.

‘They would not listen, they are not listening still, perhaps they never will,’ ended Don Mclean’s classic ode Vincent. On the evidence of where we stand as a nation, as articulated by Bheed, we are obviously not listening, and perhaps never will.

(Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri is a film and music buff, editor, publisher, film critic and writer)