Much has been written about Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose and his Indian National Army, or the Azad Hind Fauj; films such as Shyam Benegal’s 2004 biopic Bose: The Forgotten Hero dwell on this as well. But surprisingly, no major film has been made on the INA trials, one of the most telling events in the run-up to Independence. Tigmanshu Dhulia’s Raag Desh, produced by Rajya Sabha Television, attempts a celluloid retelling of the trials, the backdrop of which is well known.

As World War II engulfed southeast Asia, Japan made spectacular advances culminating in the fall of Singapore in February 1942. Around 55,000 Indian troops stationed there became prisoners of war. A section of the surrendered soldiers decided to form the INA helped by the Japanese, but this was soon dissolved. Around June 1943, Netaji reached Singapore, reorganised the unit and formed the Free Azad Hind government that got recognition from, among others, Nazi Germany, Mussolini’s Italy, Thailand and the puppet regimes of Croatia and Burma. In October of that year, the Azad Hind government declared war on Britain and the US and the following month, the Imperial Japanese government granted it some jurisdiction over the Andaman islands which it had occupied in March 1942. The INA also fought alongside the Japanese in the Kohima and Imphal theatres in 1944. However, the tide of the war started changing after the Normandy landings in June 1944 and by early 1945, the Allies mounted a successful campaign to secure southeast Asia through Burma. With the Japanese retreating and starved of men, weapons and ammunition, though not necessarily their spirit, the INA soldiers surrendered and were taken prisoners-of-war by the British.

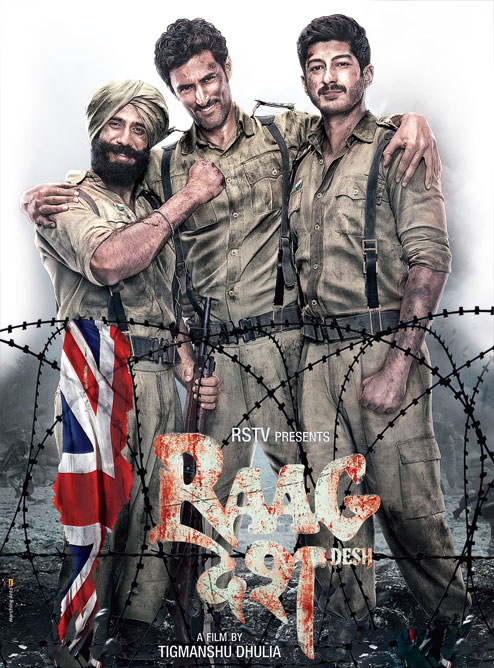

Dhulia tells this history through flashbacks, which keep going back and forth through the movie, and through the tales of the three protagonists: Colonel Prem Sahgal (Mohit Marwah), Colonel Gurbaksh Singh Dhillon (Amit Sadh) and Major General Shah Nawaz Khan (Kunal Kapoor). All three had been officers in the British Indian Army and were taken as PoWs in Malaya, Singapore and Burma.

The British, keen to teach the “renegades” a lesson, decided to hold their court-martial through public hearings at Red Fort — the site chosen deliberately since Netaji, giving his “Chalo Dilli” call, had vowed to fly the Azad Hind Tricolour from its ramparts.

The first of these trials began on November 5, 1945, with the trio of Dhillon, Khan and Sahgal accused of the serious crime of waging war against the King-Emperor under the Indian Army Act — akin to charges of treason. Besides, Dhillon was accused of murder and the two others of abetment to murder for killing British Indian troops.

The trials, carried out by the Military Tribunal, so captured the imagination of the people that the Congress and Muslim League, in a rare show of unity in India of the ’40s, launched public protests and made the release of the trio a big issue. The Congress, initially ambivalent on the INA, set up a defence committee with the brilliant but ailing lawyer Bhulabhai Desai at the helm assisted by Tej Bahadur Sapru, Pandit Nehru and K.N. Katju.

But it is in the courtroom scenes that Dhulia falters. The testimonies are too often interrupted by flashbacks which affect the focus of the audience. Dhulia could well have focused on the arguments and counter-arguments since he had the actors to do the job for him. A case in point is Stanley Kramer’s classic Judgment at Nuremberg which keeps the viewer riveted thanks to a tight script and the performances of Burt Lancaster, Maximilan Schell and Spencer Tracy among others.

Kenneth Desai, playing Bhulabhai Desai, does an excellent job as the ailing but razor-sharp lawyer but one wishes the writer (Dhulia himself) had brought out the brilliance of his arguments: the crux of which was the legal right of an enslaved nation to wage a war of independence against its foreign ruler, probably the first time anyone made this argument in any court of law.

Where the film also misses out is in highlighting the human impact of the trials. The activities of the INA were not known to the Indian masses in all detail because of the censorship imposed by the British. But by ordering the trials, the British unwittingly raised a public outcry. The arguments made it to the front pages of all newspapers, sparking what one journalist had then described as an “explosive surge of nationalist fervour”. Dhulia touches upon this in brief but how the change in mood came about could have been shown in greater detail.

The trials ended on December 31, 1945, and as expected the tribunal found the trio guilty of waging war against the King. They were sentenced to deportation for life but sensing the public mood, Army commander-in-chief Claude Auchinleck commuted their sentence.

By then, the story of the INA had reverberated through the military, the key pillar through which the British exercised authority over Indians. Within two months, the Naval mutiny broke out in Bombay and spread all over, hastening the departure of the British.

Dhulia, who directed the brilliant Paan Singh Tomar, gets uniformly good performances from his actors. Kapoor and Marwah shine, the latter’s love story with Captain Lakshmi Swaminathan (Mrudali Murali) — who headed the Rani Jhansi regiment of the INA — forming a sweet sidelight. But it is Amit Sadh who packs a punch with his portrayal of Dhillon: in one particularly emotive scene, the colonel, tasked with executing traitors, convinces his reluctant men to pull the trigger because for him the honour of the army and freedom is above everything. Kanwaljit Singh, as Sahgal’s father, has a nice cameo. A lot of research has gone into the film since almost every leading personality from the times is shown: Churchill, watching a film on screen, is told about the famine in Calcutta to which he makes his famous reply: “Why hasn’t Gandhi died yet?”

Netaji, played by Assamese actor Kenny Basumatary, has a few scenes exhorting his troops to give him blood in exchange for freedom. The war scenes are a letdown, the grit missing from them. Possibly Dhulia had to make do with a tight budget but the editing could have been better. The INA’s famous Kadam kadam badhaye ja resonates all through the 137 minutes of the film, otherwise the music is not too memorable.

But these are minor quibbles in what is otherwise an important work. Maybe someday another director would attempt another film on the event that captured the imagination of the youth of the day and triggered the exit of an imperial occupying power. Tigmanshu Dhulia has given them a foundation.