|

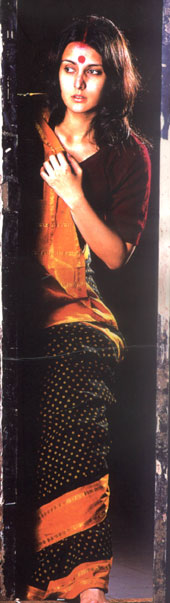

| BLEAK HOUSE: Tulip Joshi, who plays the protagonist, in a scene from the film; (below) Manish Jha |

|

In a village somewhere in north India, a woman is in labour. Time and again she kicks her legs in agony as the midwife urges her on. Outside the hut, the unborn child's father awaits restlessly. As the first cries of the baby are heard, the men outside break into a spontaneous jig.

Until, the midwife breaks the news to them. “It’s a girl,” she says. And the celebration stops. What follows thereafter in director Manish Jha’s debut feature, Matrubhoomi: A Nation Without Women, is one of the most chilling scenes ever shown in Hindi films. Busy hands hurriedly fill up a giant cauldron with milk. Then two hands gently but firmly lower the new-born baby into the small sea of liquid. Bubbles rise for a few seconds. Soon, they stop. “Next year, a boy,” says a male voice.

According to a recent report by the Union ministry of health and United Nations Population Fund, about 35 million girls went missing in the past 100 years due to gender discrimination. Contrary to popular perception, such practices are prevalent both in rural as well as urban India leading to a lopsided male-female ratio (1000:933). Benita Sharma, on the Delhi government advisory committee for women’s health, says the problem exists in educated and affluent homes too. She points out that South Delhi has one of the worst male-female ratios and that doctors openly advertise amniocentesis in many Haryana towns. “The issue of female infanticide needs to be addressed on a war footing,” says Sharma.

In Matrubhoomi, Jha conjures up a time and place where due to unchecked and widespread killing of the girl child, women have nearly become extinct. Their absence leads to the dehumanisation of their menfolk who indulge in pornography, bestiality, homosexuality and violence. When the desperate men finally spot a teenage girl, she is immediately bought at a good price. Then, she becomes the collective wife of five brothers and their father.

The story is frightening and sad in equal measure. And Jha pulls no punches. The movie’s mood is dark, the humour black and the violence gut-wrenching. Says the filmmaker, whose documentary, A Very Very Silent Film, won the Jury Prize for the Best Short Film at the Cannes film festival in 2002, “I didn’t intend to go out with the idea of making a hard-hitting film. It just turned out that way.” Then he adds: “When you are dealing with a subject like female infanticide, you cannot soft peddle.”

Matrubhoomi was first shown at the Venice Film Festival back in October 2003 where it won an award for the Best Film in the non-competitive section. Over the next few months, it won a clutch of prizes at different international film festivals the world over, notably the audience award for the Best Foreign Film at Kozlin, Poland, in 2003 and again in Florence the same year.

Winning over the foreign audience was easy. Making the film available to its target audience at home was more difficult. Matrubhoomi was completed in October 2003 and Jha avoids going into the reasons behind the delay in its commercial release. It appears that Boney Kapoor, who owns the film’s rights in India, was looking for an appropriate moment to release it.

But now, 18 months since its completion, Matrubhoomi is scheduled to be released all over India next month. The good news is that the film has also been dubbed in five languages apart from Hindi ? Bengali, Tamil, Telugu, Bhojpuri and Gujarati. Jha says his aim is to reach out to the maximum number of people, both in the multiplexes and in the interiors of the country. “Releasing the film in different languages will hopefully help achieve that,” he says.

The idea of Matrubhoomi first came to Jha when he read about a village without women in Gujarat in a news magazine. Then one night in Paris while surfing the Net, he came across an article that said that over the years, millions of girl children had fallen victims to gender discrimination in India. “If you are born in Bihar and grow up in Delhi, you witness social prejudices and biases against women at close quarters. Every sensitive man is affected by this discrimination,” he says.

So when French producer Patrick Sobelman asked him to produce an outline for a script on the subject, he immediately put out a two-page synopsis. Then he wrote down a huge 200-page script but hacked it to 70 pages, all within the space of a week. When he found Pankej Kharabanda to co-produce the movie, the project was on.

Filmed on a tight budget of Rs 2 crore, Matrubhoomi was shot in Renai, a remote Madhya Pradesh village, and completed in 29 days. And while filming, Jha realised how fact was really very close to fiction. Even as thousands of men from the neighbouring villages saw the shooting, women merely peeped behind the windows and half-closed doors. “There were at least 10 women in the main house where we shot the film. But we never saw them,” recalls Jha, “It was like life imitating art.”

The first emotion that hits anybody watching Matrubhoomi is shock. Shame follows. And, ultimately, one feels drained. It is a benumbing experience. Jha’s vision of a nation without women is bleak. It is a world where a father sells off his daughter, where a father-in-law sleeps with his daughter-in-law and where brothers conspire to kill the sibling who is closest to their collective wife.

Born in Bettiah, Bihar, Jha grew up and came to Delhi at an early age. All he ever wanted was to keep his hair long and act. But when he approached the theatre group at Delhi’s Ramjas College, he was asked to first chop off his long hair.

He moved to Mumbai and worked as an assistant director in television serials hoping to get a break. It never came. Desperate, he put in Rs 30,000 to make a five-minute long documentary on the homeless that won a prize at Cannes.

Matrubhoomi, with all its international awards, seems to have taken him a step further. Jha believes that his future as a director depends on the success or failure of the film. That may not be strictly the case as Jha seems to have carved a niche for himself that goes beyond the film’s commercial success.

For it is undeniable that Matrubhoomi is both a powerful and a relevant film. As the film’s co-producer Kharabanda wonders: “In the past few weeks, every newspaper has published articles on saving the tiger. But considering the alarming number of female infanticide, don’t you think the media should focus on that as well?”