|

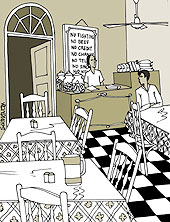

No talking to cashier/ No smoking/ No fighting/ No credit/ No outside food/ No sitting long/ No talking loud/ No spitting/ No bargaining/ No water to outsiders/ No change/ No telephone/ No match sticks/ No discussing gambling/ No newspaper/ No combing/ No beef/ No leg on chair/ No hard liquor allowed/ No address enquiry/ — By order.

These instructions on a notice board at Bastani & Co are no longer visible at Mumbai’s best loved Irani restaurant. Long before the Irani eatery closed down, this notice board passed into something indestructible — Mumbai’s collective consciousness.

That’s perhaps why the news of Bastani’s sudden closure evoked a sense of shock and loss. Old Parsis wrote letters to the editor bemoaning its loss. Frantic e-mails and smss were exchanged between those who knew the magic of this quaint café tucked in the corner of Dhobi Talao in south Mumbai. The adda is over. And so is another chapter that symbolised Mumbai’s cosmopolitan melting pot.

“It is as if a part of our life has been lost,” wrote letter writer Bhikaji Adenwalla in a city eveninger. “Pack up the elegant bentwood chairs, eat the last cake, wash the chipped teacups one last time, throw the checked table cloths into the laundry basket, keep one of the menus as a souvenir, take down the picture of Zarathustra, and wipe off the dust of years, chase the cat out, wash every one of the huge glass jars that held the biscuits, and put them in storage, sell the place to someone who will tear out the wooden pillars with their mirrors, get rid of a piece of history as easily as one of the perpetually grumpy waiters would wipe a tea-stain off the glass-topped table… Sorry: No Irani restaurant here,” wrote an exasperated internet blogger on his blogspot.

Everyone who heard the news ached with a memory. Bastani was home to many of Mumbai’s ordinary citizens. In the afternoon, the lawyers from the Small Causes Court came to gorge on Bastani’s famous chicken biryani or kheema-pau flaunting their black coats. Students of St Xavier’s College spent more time in Bastani and its equally old rival, Kyani & Co. than in their college canteen. In the evening, the café’s regular patrons dropped in to pick up bakery-made Shrewsbury or wine biscuits or freshly-made mava cakes neatly stacked in glass jars. One would spot Mumbai’s famous names like painter M.F. Husain, veteran journalist Behram Contractor, cartoonist Mario Miranda enjoying a plate of bun-maska (copious amounts of butter sandwiched between sliced bun bread). The marble-topped round tables covered with bright checked table cloths and wooden chairs gave a Parisian feel to the place.

“Bastani is a huge loss to our cultural and culinary heritage. Irani cafés symbolise Mumbai’s communal harmony like nothing else does,” said heritage activist Sharada Dwivedi, who co-authored Mumbai — The Cities Within.

According to Dwivedi, the Irani immigrants began arriving in Mumbai in the 19th century when the city was expanding rapidly. The British had introduced the railway services, the Mumbai Port Trust had opened the harbour boosting trade, the municipal corporation had been formed to shape the city’s civic growth. “The Portuguese had introduced Mumbai to the technique of yeast bread or the pau as we know it. Initially it was to supply the army. The demand for the pau and the bakeries further grew as the British took over and early migration began. The Parsi and Muslim Iranis found it a good business. By 1901, there were 1400 bakeries, according to The Gazetteer,” says Dwivedi.

The Irani migrants took the business a step ahead and started restaurants which sold their bakery products as well as non-vegetarian dishes. Slowly, each Irani restaurant developed its own culinary specialities. Britannia in Ballard Estate became famous for its Berry Pulao; Sassanian Boulangerie at Dhobi Talao for its Parsi food. Kyani & Co for its bakery products; New Excelsior café for its kheema-pau. But, two things remained common to all of them — distinct watery, milky tea, and a leisurely sense of time.

Another interesting feature of Irani restaurants is that most of them are located at street corners in prominent places in Mumbai. “Those days the other communities, especially the Hindus, regarded the corner establishments as unlucky. So, we got them at throwaway prices,” recalled septuagenarian Boman Rashid Kohinoor, one of the six partners of Bastani & Co., a few months before the closure of the café. The marble-topped tables and chairs were imported from Belgium.

Like most spacious Irani cafés, Bastani also had a mezzanine floor which served lager beer. But as beer bar culture invaded Mumbai, especially in the last decade, and bar licences became expensive, Bastani had to close down the bar. The sleekly marketed coffee-house chains like Barista and Café Coffee Day further eroded the clientele of Irani restaurants.

“Time is the destroyer and time is the greatest healer,” mused 43-year-old Farhad Ottovari of Kyani & Co., looking wistfully at the closed gates of his rival for years just across the road. Ottovari’s father arrived in Mumbai as a migrant and joined the other partners in this café that dates back to 1904. Unlike Ottovari, most of the second generation of these families found the restaurant business too taxing and stayed away from it.

Another problem plaguing the Irani cafés is the legal disputes between partners. By the 1990s, when the construction boom began, these cafés had become landmarks located in the costliest real estate in the country.

“The moment you tried to innovate to improve business, the partners tried to stifle the move. The story of Irani cafés starts with fights and ends in the court receivers office,” said Behrooz Khosravi, a partner in erstwhile New Empire café which was leased out to McDonald’s. McDonald’s, perched on prized real estate located opposite the Victoria Terminus, now rakes in the moolah with its two-minute burgers.

The Irani cafés have long been a part of Mumbai’s literature, cinema and theatre. From Govind Nihalani’s 1983 classic Ardh Satya to M.F. Husain’s Meenaxi — A Tale of Three Cities, the cafés have been part of film sequences. Writer-director Shiv Subramanyam, best known for his screenplays of Vidhu Vinod Chopra’s Parinda and 1942 A Love Story, staged his play Irani Café at Prithvi Theatre Festival in 2002. He is currently trying to make a film on it starring Sushma Reddy. “It is about a bunch of people who frequent the Irani Café,” said Subramanyam, who used to frequent the Irani Café Mayrose during his days at St Xavier’s College.

But, poet Nissim Ezekiel, who succumbed to Alzheimer’s last year, perhaps paid the best tribute to the Irani cafés and his subject was the queer notice board at Bastani:

Please/ Do not spit/

Do not sit more/ Pay promptly, time is invaluable/ Do not write letter/ Without order refreshment/ Do not comb/ Hair is spoiling floor/ Do not make mischiefs in cabin/Our waiter is reporting/ Come again/ All are welcome whatever cast/ If not satisfied tell us/ Otherwise tell others/ GOD IS GREAT