|

|

|

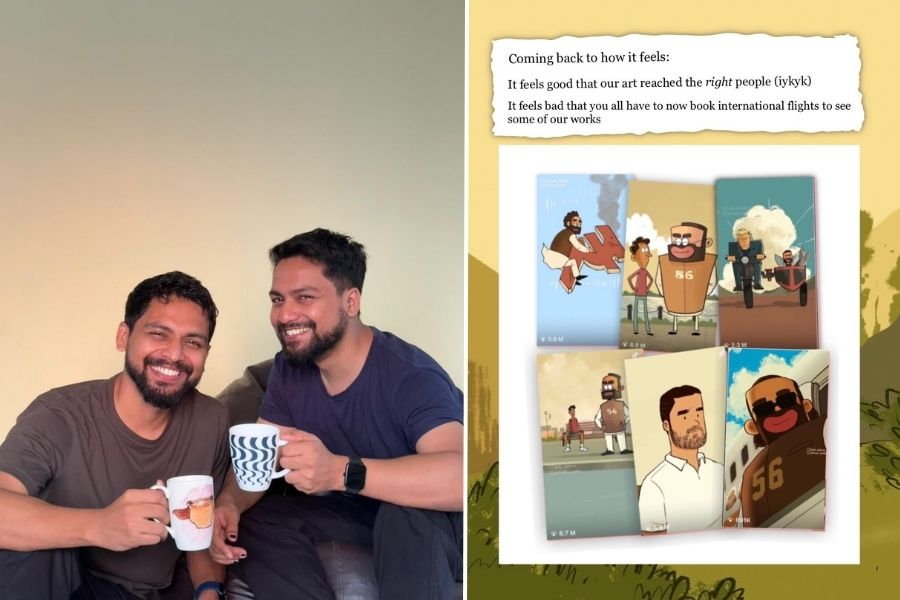

| Different strokes: (from top) A widow in Vrindavan; a Bengali bride; the book cover |

My sharpest memory of her,? writes Mary Roy, author Arundhati Roy?s mother, about her own mother in an essay entitled, ?Three Generations of Women?, ?is when I was a four-year-old child and she was a young and beautiful woman. Standing in the living room dressed in white, with blood flowing from the wounds on her head. Scars inflicted by her Imperial entomologist husband wielding the Imperial curtain rods with which he beat his wife?.

The deeply personal essay, which went on to record her memories of the circumstances of her mother?s life, and subsequently her own and her daughter?s, was written for a workshop on women?s lives, organised by the Centre for Development Studies (CDS), held at Trivandrum in 1998. Now, it is part of a newly-released book ? a collection of women?s personal narratives ? called A Space of Her Own (Sage Publications). Edited jointly by Jashodhara Bagchi and Leela Gulati, the volume comprises the personal accounts of 12 eminent women ? including Roy, Bagchi and Gulati ? nine of them prepared for the CDS seminar. Initially, these ?three-generational narratives?, as they were termed at the conference, were compiled into a volume ? Journal of Gender Studies. Three other essays were later added, when it was decided that the present collection would be brought out.

?The earlier essays showed how the personal narratives of women, drawn from memory, revealed so much, so many details, about the lives of women of different generations, their relationships with each other and the people around them,? says Jashodhara Bagchi, pointing out how the idea for the present volume emerged. ?It was obvious that these were more than just personal narratives. These were, in many ways, also helping recreate the social history not just of women, but of the world around them?.

Roy?s account, for instance, communicates the sheer horror of getting a divorce for women of her mother?s generation. ?My mother?s white clothes, drenched in blood, were carefully stacked away,? she writes. ?They were given to her brother (my uncle) who was a director of the International Labour Organisation (ILO) in Geneva. My uncle took the clothes to a firm of lawyers, M/s. King and Partridge? In those days, they were asked to draw up a case for divorce. My father was incensed and for years after would refer to me as Mrs Patridge and to my sister as Mrs King? The uncle died, my grandfather (Mother?s father) died and the beatings continued with monotonous regularity, and no one in Mother?s family remained to act as an occasional check.?

Zarina Bhatty?s memories recorded in ?A Daughter of Awadh?, go back to a time when Indian society practised secularism without fuss. ?Now when I visit Lucknow, the city of my birth,? she writes, ?my niece greets me with the Arabic salutation, salaamalai kum (may God be with you). I reply rather hesitantly, walai kum assalam (may God be with you, too) and the words sound strange to my ears. As a child I used the more secular adaab or tasleem spoken in Urdu, the language of poetry and refinement. This ancient, teeming city has seen much change between then and now. My mother, uneducated and unexposed behind the walls of purdah, used to send us properly escorted by a servant to enjoy the festivities of Diwali and Dussehra with our Hindu neighbours.?

So many other women had so many more stories to tell. In fact, points out Bagchi, the idea to hold the Trivandrum conference had first come to Gulati, when she was working on a book which focused on the personal lives of underprivileged working women. She, along with Arlie Hochschild (one of the contributing authors), who was a Fulbright Visiting Fellow at the Centre, thought it would be a good idea to ask other women to ?reflect on the lives of their mothers and their grandmothers in relation to their own lives?.

But unlike Gulati?s profiles, A Space of Her Own comprises the narratives of women who, Bagchi admits, ?come from backgrounds of a certain amount of privilege?. They are all educated and if not writers, all, are definitely ?achievers? in different ways. But Bagchi points out, ?Their stories are not statements of privilege but of struggle,? and in that sense the current volume helps bridge the gap between women of myriad social and economic strata, uniting them with a common theme. ?The privileges of background do not mitigate the pain that fills the pages,? Bagchi says.

Yes, as Nabaneeta Dev Sen writes in ?The Wind Beneath My Wings?, her grandmother Narayani ?was the daughter of an aristocratic feudal family, the Duttas of Hatkhola, who appear in the history of Calcutta city?. But still, writes Dev Sen, she didn?t get a mention in her favourite son?s family history. ?She was a nameless person, whose only identity was to have borne a dozen offspring (six of each sex)?.

And she writes about her mother?s pain: ?In her last years, after she was 80, my mother used to tell me that I was her only friend?. And about her own ? the heart-break of a failed marriage. ?When my marriage fell apart, I was 34. By then I had lived at 11 addresses with my husband in the United States, England and India, had two lovely children and two heart-rending miscarriages, several degrees and never held a job. I was stupefied at first. I had not realised that it was a bad marriage. I had always taken us to be a happy couple. I thought I had a wonderful husband, and was quite a good wife, mother and hostess, and had gathered some confidence in myself. Though Amartya could not be useful around the house since he was much too busy, he seemed to me to be a loving and caring husband. To my great surprise, I was told that he was not in love with me anymore.?

Maithreyi Krishna Raj?s childhood memories are similarly laced with pain. ?In Wings Come to Those Who Fly?, she writes, ?My sister and I were very attached to our mother. We loved her deeply. Her death was a terrible blow to us. I can still remember the tragedy and oppression of my mother?s life as if it happened just yesterday. I remember my mother. She was thin, worn out with work. At 32, she looked ancient. Her day began long before we were up and ended long after we were all in bed. My memories of her are very vivid ? a frail figure, clouded by the swirling wood smoke of the kitchen fire that stung our eyes. She staggered under pots of water fetched from wells near or far. We saw her bent over endless household tasks.?

But through the aching words, emerges, unmistakably, the voice of courage that these women must have themselves heard from within and the strength that must have kept these women going helping next generations to grow. In the introduction, Carolyn M. Elliott observes, ?The narratives in this collection provide insights on many important issues?. Among them, she names the ?subversive voice? and the ?rebellion? of some of the women writing or written about. She talks about themes emerging prominently in the life stories of the authors which point to ?renegade predecessors in the family who set out a pattern of independence?. She writes, ?Each narrative may be read as a tale of how the author established her own personhood.? Dev Sen?s mother told her ?to concentrate on my academic career and my children, and to forget about men?.

A Space of Her Own ? the title inspired by Virginia Woolf?s A Room of Her Own ? and the concept very close to Woolf?s idea of ?thinking through the eyes of our mothers?, agrees Bagchi, ?is definitely an important addition to the genre of women?s writing?.