|

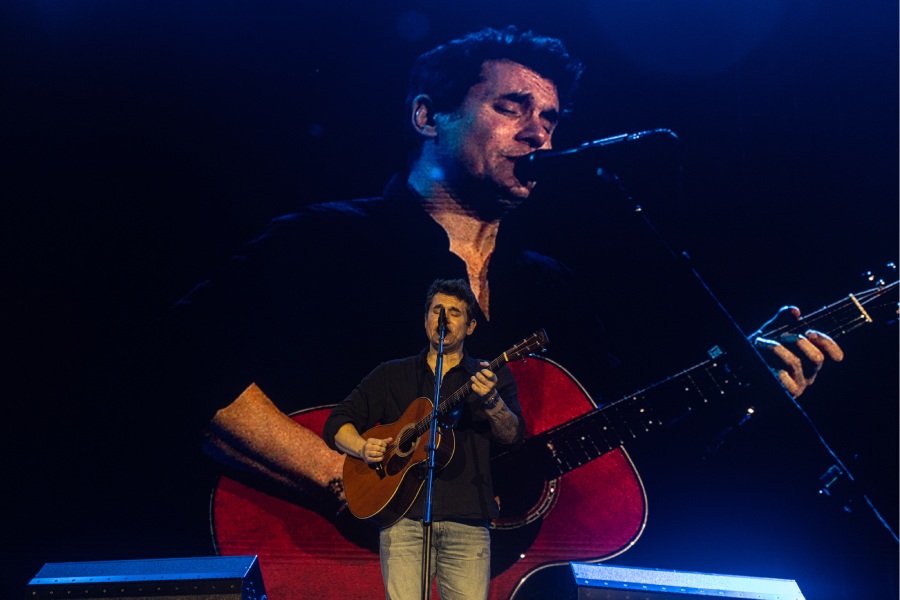

| WE Shall overcome: Varsha Kale, president , (second from right) and members of the Womanist Party of India |

You could think that it is just another group of housewives which has gathered for a tea party. But when Padma Nikam speaks, you know that there is something brewing there. And it’s not tea.

“The spark will start a forest fire. Just wait and see,” Nikam tells the six women who are sitting with her. The women maintain an expression of restless calm — but they are all there because they think it’s possible. No one in Maharashtra’s political circles may take them seriously, but when the Election Commission registered these women last month as office-bearers of the Womanist Party of India (WPI) — India’s first all-woman party — it was clear that they meant business.

A fortnight later, they are all set to start what gives even seasoned political parties the jitters — electioneering. Nikam, a former hawker, now a successful entrepreneur selling home food, and the joint secretary of the party, has to start moving before the Election Commission announces its code of conduct for the Maharashtra Legislative Assembly elections slated to be held in October. “We want to contest from all 288 seats,” says Varsha Kale, the 34-year-old national president of the party.

That the group is ambitious is clear from the fact that the party doesn’t have a proper office yet, forget funding and other electoral paraphernalia. “Everything is yet to be worked out, but I am happy that at least we have reached this stage,” says Kale, dressed in a lilac cotton sari.

For Kale, the formation of the party is the culmination of a four-year-old thought process. Belonging to a middle-class Maratha family living in Dombivili, a suburb on the outskirts of Mumbai, she was a part of a left-oriented women’s group in her college years. She left home in 1985 for Bihar where she was involved in the Jharkhand Mukti Andolan. Kale returned to Mumbai to complete her masters in Marathi literature and a course in women’s studies before plunging into active social work in the rural sector.

Kale began working with women in villages near her home in the Shahapurtaluka of Thane district. In 1991, she went to Sangli in western Maharashtra to work for an NGO on the implementation of women-oriented projects. She organised women for a campaign against alcoholism, implemented watershed development projects and organised awareness camps for adolescent girls.

“I worked in Sangli till 1996 and that’s where I was exposed to the ground reality of how strong a role caste politics plays in rural India,” she says. “A Maratha girl faced harassment from a Dalit boy in the village and I stood up for the girl. I was accused of siding with a Maratha, and I had to face the ire of both the Dalits and Maratha communities,” says Kale, who moved to Yavatmal district to continue her social work.

In Yavatmal, Kale realised that though there were thousands of women sarpanches in Maharashtra’s villages, men continued to control the political affairs at the grassroot level. “I went to a village in Yavatmal to meet a woman sarpanch, but her husband came to talk to me instead. He was running the affairs. I realised that a woman’s status at home won’t change unless her social status outside changes,” she says.

It was while she was involved in social work that she realised women were disillusioned with the mainstream political parties. “The existing political parties are not genuinely interested in women’s issues. Look at the way parties have stalled the Women’s Reservation Bill. As I discussed the idea of a women’s political party, more support poured in,” she says.

By March 23, 2003, Kale and her small group were ready with a declaration. By October, 2003, Kale had announced the party with a charter of a 21-point programme. The charter includes demands such as increased reservation for women from the current 33 per cent to 50 per cent in elected bodies, inclusion of women’s names in land ownership deeds, implementation of the Maharashtra State Women’s Policy, granting 50 per cent reservation for women on boards of co-operative banks, state corporations and other institutions, and setting up of women’s police stations, among others.

Though women are her chief constituency, Kale doesn’t want her party to associate with feminist groups or other political parties. “When we chose the symbol of our party — hands with bangles — feminist groups said bangles are a symbol of slavery. But, in our culture, bangles are the basic jewellery women wear. We represent womanism, not feminism,” she says.

WPI’s chief agenda is what they call the womanisation of politics. Kale and her associates believe that their brand of “politics of caring and sharing” is increasingly relevant in the world of “male” politics of war and terror.

But, Maharashtra’s political circles haven’t taken kindly to Kale’s party. Some alleged that the party had tacit support from NCP’s Sharad Pawar to weaken the traditional votebank of the Congress. Others say the WPI is the baby of BJP’s Pramod Mahajan. “All kinds of reports and comments have been made about us, but all we can do is laugh at all the rumour-mongering,” says Kale.

But, political analysts like Nikhil Wagle, editor of the Marathi eveninger, Mahanagar, feel Kale and her party are merely publicity-mongers who do not possess a serious political or ideological agenda. “In a democracy, every citizen has a constitutional right to start a political party. But, I do not believe that women’s issues can be resolved by women alone. Women’s problems are human rights-related and you need men as well as women to resolve them,” says Wagle, who is a strong supporter of the Women’s Reservation Bill.

Most of WPI’s members belong to families with some association with politics. Kale has a relative who was an MLA. The families of general secretary Avisha Kulkarni and vice-president Shobha Karande have worked closely with the Congress. “As a child, I was given the job of garlanding political leaders when they came to our area,” says Pune-based Karande. “I remember garlanding Indira Gandhi. But the role of women was restricted to performing traditional welcome. When it came to political discussions, women were asked to leave the room.”

Women have earlier tried — and failed — to form woman-only parties. A group of women activists even tried to fight the parliamentary elections from Delhi some years ago, but gave up the effort after encountering little popular support.

Veteran Janata Dal leader Mrinal Gore dismisses the WPI as a wasted initiative. “It won’t achieve anything,” she says. Gore argues that greater representation to women in the political process and decision-making is the need of the hour, but it cannot be achieved by segregating wom- en as a separate political entity.

“You can’t say you will only work for women’s issues. As a political representative, you have to handle all issues irrespective of gender. In fact, an all-woman party will end up hampering the process of empowerment,” says Gore, a former MLA.

Kale and her friends have heard comments like these before, but that has not dampened their spirits. They argue that women’s parties have existed in countries like the Philippines, Turkey and Australia (WPI shares uncanny similarities with the Australian Women’s Party which has been fighting for equal representation for men and women in Parliament) and seek to highlight the fact that WPI is the world’s ninth all-woman party. “I believe there have been attempts to float a women’s party before in Bihar, Rajasthan and West Bengal, but they failed to sustain the effort because they were offshoots of main political parties,” she says.

But, without a specific agenda and virtually no infrastructure in place, WPI will clearly find the going tough. Kale admits that fighting elections is an expensive and often a “dirty” game, but hopes that a massive membership drive will help her raise the funds.

Kale is optimistic that their efforts will bear fruit. Holding on to hope, after all, is winning half the battle.