|

There is something truly tragic about the fall of a legend. One moment you are up there — right on top of the world — revered and loved by millions. And then, suddenly, you are being trampled on — scorned, or even worse, sneered at.

Who would have thought that the Alphonso would one day come crashing off its pedestal? For there it was, till just the other day, the crowned king of mangoes. And here it is now, sheepishly rubbing shoulders with the hoi polloi of fruit.

For long years, it was the priciest and classiest — the caviar of the fruit world. There was a time when it was said — especially on the streets of Mumbai — that nothing could beat the Alphonso. And it helped that few outside its birthplace of Maharashtra had ever tasted the fruit. One, because most people couldn’t afford to eat an Alphonso, and two, because there was not enough of it going around.

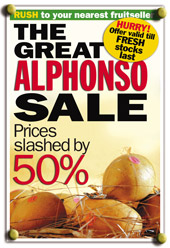

If you want an Alphonso this summer, you can just ask for it. It’s there aplenty, and at half the price that the fruit commanded five years ago. And now that the Alphonso is not quite the exclusive nectar that it was once seen as, there are quite a few people who are shaking their heads and wondering what the fuss was all about.

In a country bitterly divided into warring groups of mango lovers, the Alphonso has always been at the centre of any heated discussion on the Mangifera indica, a fruit native to southern Asia. The dedicated Alphonso aficionado’s club has always had to contend with those who love their Himsagar, a fruit that all of Bengal swears by, a group, which, in turn, will have nothing to do with fans of the southern Indian Banganapalli. Followers of the Chausa — named after a village in Malihabad — are convinced that their choice is the best. And some, who insist that they have been there and done that, will tell you that there is nothing in the country to beat the Rataul of the north.

Still, despite all the feuding, the Alphonso carried on as the king. Legend has it that Indian merchants seeking to seal a business deal in the Middle East carried boxes of Alphonsos with them. The sheikhs, it was said, were so fond of the fruit — especially of its texture and light flavour — that, when presented with the fruit, they always ended up signing a deal.

Even some years ago, if business houses such as the Reliance Industries wanted to give out gifts, they went in for a cellophane-wrapped box of Alphonsos. In a country mad about mangoes — India produces 10 million tonnes annually, accounting for 52 per cent of the world output — nobody ever said it with roses; they did so with Alphonsos. The variety was special because it was exclusive. And therein lies the story of the fall of the Alphonso.

A glut in the market — coupled with a steep fall in price —has taken the sheen of its golden skin. The Alphonso — Alfonso, Alphanso, Hapus, Appus, Badami, Gundu or call it what you will — is fast becoming a garden-variety mango, stacked high with lowly cousins in phal mandis. “The exclusivity of a product often becomes its enemy,” explains sociologist Surajit Mukherjee of the Burdwan University. “Exclusivity triggers demand, which leads to a mass production and thus kills its exclusivity,” he says.

Once, the Alphonso was grown mostly in the Ratnagiri area of Maharashtra. But as the demand for export grew — mainly because of its look, soft fibre and long shelf-life — other farmers across the coastal Konkan region started cultivating the fruit. Alphonso orchards also sprung up in neighbouring Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka — contributing to the Rs 700-crore market.

The fall of the Alphonso, ironically, is linked to efforts aimed at its growth. By the mid- Eighties, many Alphonso cultivators had moved away from the fruit, for there was just not enough money to be made, thanks to the fact that middlemen siphoned off a large chunk of the profits.

Things began to change a decade later. The Maharashtra government pitched in with subsidies as farmers started to organise themselves into unions under the aegis of non-governmental organisations. The Congress, a strong presence in the coastal belt, backed the farmers in their fight against the middlemen.

By 1995, farmers had started selling their produce directly to mango merchants in Mumbai. “Earlier, a broker would charge Rs 600 or so from us as commission for every six dozens mangoes sold. We don’t pay that amount any more,” says Vidyadhar Joshi, a mango farmer from Ratnagiri’s Deogad area.

The production went up, and the prices came down. Congress legislator Sudhir Sawant, who is familiar with the trade, says the production increased from 1.7 lakh metric tonnes in 2000 to 2.5 lakh metric tonnes this year. Not surprisingly, Rumi Ranji of the Golden Star Thali, a popular Mumbai joint known for its aamras from Alphonsos, paid as little as Rs 850 for four dozen Alphonsos this year. Five years ago, 48 mangoes had cost him Rs 2,000.

There was a time, officials recall, when every summer the aroma of ripe Alphonsos wafted through the dingy corridors of the Mantralaya, the state secretariat in the heart of the country’s commercial capital. Short of filthy lucre, nothing else was as powerful as boxes of Alphonsos to prevent files from gathering dust in many a department. “But this is no longer the case. Very few now ask or give Alphonsos as bhet. The mango seems to have lost its status,” a retired Maharashtra-cadre IAS officer says.

A gift from the Ambanis is these days mostly a box of dry fruit. “No one likes to receive perishable mangoes as gifts any more,” says an industry insider. Adds Farzana Contractor, editor of the high-life magazine, Upper Crust: “It was a status symbol to send and receive Alphonsos, but it’s fading now.”

Though Alphonsos still make up the bulk of the mangoes India exports, other varieties are fast catching up. Uttar Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh and West Bengal — three major mango-producing states — have started exporting varieties such as the Langra, Chausa, Dussehri and Mallika in a big way.

The West Bengal State Food Processing and Horticulture Development Corporation, for instance, is sending 15 tonnes of Himsagar and Mallika mangoes to Britain this year. “Alphonsos once had the monopoly in the international market, but we have now joined in,” says the corporation’s MD, Nikhilendu Hajra.

Now that the Alphonso is down, supporters of other mangoes are doing their bit to further the cause of their own favourites. “I have tasted the Alphonso, but nothing can beat our Himsagar,” says Sunil Gangopadhyay, the well-known Bengali writer and a mango-lover. And Pune-based food writer Karen Anand, who grew up in Chennai, points out that for a Tamil, there is nothing to beat the Malgoa or Maganpali.

There are some who hold the banner up for the Anwar Rataul — a mango that originated as a superior chance seedling in Shora-e-Afaq garden in Rataul in western Uttar Pradesh. General Pervez Musharraf of Pakistan, where the sweet, fibre-free fruit grows as well, made quite a few friends by sending crates of the mango to politicians across the border, including India’s President and just deposed Prime Minister.

Then, of course, there are the fans of the Langra — a mango variety that got its name from a lame fakir in Varanasi, in whose backyard the fruit is said to have made its first appearance.

Mangoes, clearly, continue to excite passions. In some corners, the Alphonso is being roundly abused as an overrated, much-hyped variety. “It certainly doesn’t deserve the attention it’s got,” Contractor says. “There are many kinds of mangoes which are as good as, if not better than, the Alphonso.”

Alphonso-lovers — and there are quite a few zealots around — disagree. “The exclusivity of the Alphonsos may have reduced a bit, but that’s because its availability at different places has increased,” says ad-filmmaker Prahlad Kakkar, who has thrown himself into promoting the variety.

Fruit-lovers — cutting across mango-lines — are all for promoting the fruit. An increase in production, they argue, eventually boils down to more mango for eating. And let a thousand mangoes ripen.

|

Connoisseur’s Delight

The best of mangoes found their place in Emperor Akbar’s orchard of a hundred thousand mango trees in Darbhanga. It is said of Akbar’s orchard that it had every rare variety culled from across the subcontinent. Two generations later, Shah Jahan went a step further — in a royal edict, he lifted the ancient ban on the grafting of saplings. The results of this were far-reaching during the late 18th century. The Murshidabad nawabs nurtured new breeds that became legendary for their taste and quality. Mulayam Jam, Nawab Pasand, Inayat Pasand — mangoes were named after members of the royal family. Here are a few of the rayeez varieties from the orchards of Murshidabad.

• Kohitoor

Legend has it that this famous nawabi variety from the Hakim Aga Mohammadi Bagh was so delicate that it had to be plucked from the tree by hand. It would lose its taste if it fell to the ground. Golden yellow in colour, the Kohitoor has to be kept wrapped in cotton wool to keep it fresh. And after every 12 hours, the mango has to be turned on its side so that it ripens uniformly. It has to be sliced with a sharp bamboo wedge, and not a knife.

• Mirza Pasand

This variety comes from the legendary Kokasbagh orchards and is named after the Mirza of Manpur. The stories around this mango are a part of Murshidabad folklore. Mirza Sahab apparently named it among his four most precious possessions in the world. And when he had to choose a gift for the Murshidabad royal family, he sent them a graft of the Mirza Pasand. The mango ripens mostly in late June and early July.

• Hauz-i-kausar

One of the rarest of the royal breeds, it grew in the Rayeezbagh orchard of Murshidabad. This variety was almost like a pet of the royal family. It’s related to the Kala Pahari mango of Lucknow, and weighs upto 500 grams. When fully ripe, its smell is like an intoxicant.

• Lazzat Bux

It was also known as the Saranga of Paharpur, and was nurtured by Nawab Suja-ul-Mulk Asif-ud-Daulah. Its sweetness can post a challenge to our favourite Himsagar, and it fit for eating only when dark spots start appearing on its tender skin. It usually comes in a small size and can often weigh upto 250 gm.

• Sultan Pasand

Another rare and costly variety from the royal gardens. It was famous for its colours — the skin combines many shades of yellow and red — and its fragrance. It is a heavy variety and is roundish in shape. It’s among the last mangoes to ripen in late July.

Satadru Ojha