|

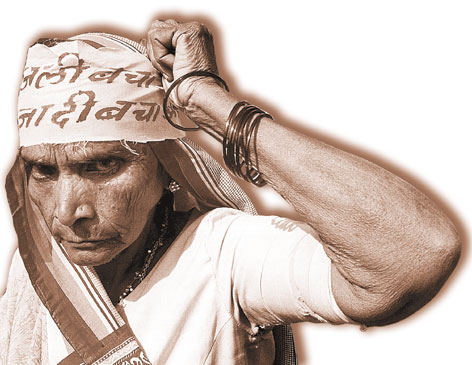

| SIDELINED: Once the movement was over, women’s groups would disintegrate because they did not receive much backing from men |

Jambabati Bijra did what no man in her village dared do. With her children in tow, the tribal woman threw herself in front of a police van, forcing the law enforcers to turn away. It was mid-eighties. The agitation against the Bharat Aluminium Company or Balco’s mining project in the bauxite-rich Gandhamardan hills in western Orissa was at its peak.

Like most villagers from Dunguripalli, her village, Jambabati, then 20, leapt to the defence of the scared hills, mentioned in the Ramayana. To her, Gandhamardan was not just a pilgrimage with temples of Lord Nrusinghanath and Harishankar on top. It was also a source of livelihood, with the hills swathed in forests and medicinal plants.

With her husband by her side, Jambabati vowed to save the hills, no matter what. She took part when villagers staged a sit-in at the block development office, demanding the project be scrapped. She jumped in when villagers tried one day to block Balco trucks from reaching Paikmal, the block headquarters.

It wasn’t easy. With the Orissa government giving the project the green light, the state administration was all set to push it through at any cost. As the news of the blockade reached the district headquarters, the collector came rushing to the spot, with platoons of policemen in tow. He asked the villagers to clear the road. They refused. The policemen were then ordered to get back in their vehicles and drive through the crowds of men and women blocking the narrow road. As the police van in front roared to life, Jambabati hurled herself in front of it. Her children too joined her, forcing the driver to slam on the brake. The collector leapt out of his car and ordered the woman to move away. “What’s the point of living if you take away our livelihood and let us die anyway,” she answered. The official tried to argue, but Jambabati, lying on the road with her children, would not budge. Eventually, the law enforcers gave up and turned back.

She is not the only woman who’s flung herself headlong into the mass movements, mostly against large-scale displacements, in the country. Many others have. But their “contributions and sacrifices” often escape the limelight, hogged mainly by their fellow male agitators, a recent study conducted by the Bhubaneswar-based Institute for Socio-Economic Development concludes.

The study, conducted on eight major projects in Orissa and Jharkhand, found that a large number of women had actively participated in the movements against displacement. And they often led from the front. Though they worked shoulder to shoulder with the men and managed to stall some of these “anti-people” projects, their efforts were never recognised. Jambabati Bijra is a case in point. While the men stood transfixed in her village in the face of threats from the police, she did not even blink before putting her life — and the lives of her children — on the line.

She paid a heavy price even after Balco withdrew from the Gandhamardan project in the face of mounting agitation. Her husband, a casual employee with the local national highway office, was sacked for letting his wife agitate against the government-backed project. “This shows the level a government can stoop to,” Balaji Pandey, director of the institute, says. At times, men, too, give their fellow women agitators the short shrift, using them “as a pawn” in the fight against the big companies and government. In the end, the women “felt left out as the men took all the credit for the movements,” says Pandey.

The study touched on women’s participation in five movements in Orissa and three in Jharkhand. They include: the missile testing range in Baliapal, the aluminium projects in the Gandhamardan and Kashipur, the aquatic project in Chilka, the Koel Karo hydroelectricity project and the Subarnarekha multipurpose project. It was not easy to conduct the study involving extensive fieldwork. Since most of the movements took place a long time ago, in 1970s and 1980s, Pandey says it was hard for the institute to track down the people involved, especially the women. In the studied areas, only a handful of elderly people still remembered the past movements. But then, they were far keener on “talking about the movements than the women who had participated in these,” he says.

Baliapal — where the Centre bowed to public pressure and shifted its proposed missile testing range in late 1980s — is one of the successful mass movements in the country against large-scale displacement and dislocation. Located on the coast of Orissa, Baliapal supplies the country with much of its requirements for paan or betel leaves. Thousands of people took to the street as they feared losing their livelihood to the proposed missile range. Though the movement owed its popularity to relentless efforts made by two men — Gadadhar Giri and Gannanath Patra — women too played a substantial role. Sumati Pundit of Kalsimuli villages is one of the many women who could not ignore the fervent appeals by the movement leaders. It was 1986. Sumati was barely 25 at the time. As the agitation intensified, the government cracked down. Activists were arrested randomly and thrown in jail. An economic blockade was set up, preventing kerosene and other essentials from reaching Baliapal. Helicopters hovered overhead, dropping warning leaflets. It was then the women took the lead. The women activists virtually allowed themselves to be used as human shields, walking in front of the men in a rally. They “wanted to give their lives first before anything happened to the men,” the study quotes Sumati as saying. The logic was simple: the movement would weaken if anything happened to the men.

There were several women groups operating in Baliapal at that time. But once the movement was over, these groups disintegrated because they did not receive much backing from the menfolk, the former activist says.

Another grassroots movement — the Koel Karo movement against the hydroelectricity project in Jharkhand — would not have been possible without the women, the study says. It was in 1950 that the project to generate 710MW electricity through two dams on the Koel and Karo rivers was conceived. But it took the Bihar government nearly two-and-a-half decades to complete the survey and prepare a report. The project was handed over to the National Hydel Power Corporation in 1980. The work on the project still drags on because of continued resistance. The project was to affect 256 villages and displace 1,50,000 people, the study says, quoting a non-government survey.

The tribal women have helped sustain the movement in a big way here. Under the banner of the Kendriya Jan Sangathan Samity, women first barred the paramilitaries, posted in that “disturbed” area, from using their wells for water and their fields for toilet. Finally, they attacked them with brooms one day and dismantled their tents. It wasn’t long before the government decided to withdraw the paramilitaries from the area. With the men protesting against the project, they raised their fists in the air and shouted slogans “hum khoon denge, lekin jamin nehi denge (we will give our blood, but not our land).” When the chief engineer of the Koel Karo project visited a dam site on June 25, 1995, a contingent of women gheraoed him. They released him only after he promised not to return.

It was, however, not easy for women to wage their struggle. In tribal heartland, where the so-called development projects often drive thousands from their home, a woman has to work in the fields, cook and feed her children. Then only can she think of joining in the movement. But for all that, the Jambabati Bijras come forward. At great personal cost, they take up cudgels on behalf of their villages. Then, they fade away — into the sunset.