|

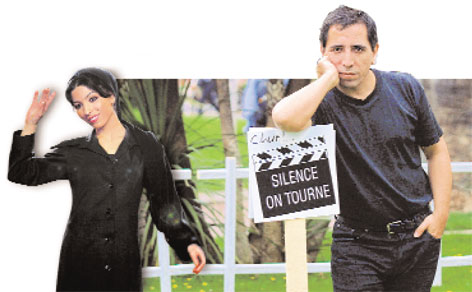

| Directors’ take: Mohsen Makhmalbaf and his daughter Samira ( left). |

At three in the afternoon, Samira Makhmalbaf doesn’t want to speak. “I’m very sleepy,” says a shrill voice on the phone. It’s Friday, the Osian Cinefan Film Festival’s opening day in New Delhi, their plane is four hours late and their clocks are still running according to Iran Standard Time. All the Makhmalbafs want to do is rest.

At 5.30, the clan descends on the hotel foyer dressed in black. Mohsen, the father, is easily recognisable from all the film festival brochures, although the clean shaven, stocky man is a tad different from the lean, moustached one that is his most popular photograph. Daughters Samira and Hana, dressed in black trouser suits and chunky jewellery, could have passed off as American girls but for the chador around their heads.

Son Maysam can pass off as anyone. The family is like any other, father and children. With a difference. They are all guests of honour at the Cinefan festival, and each of them have directed at least one of the movies being shown this year.

Shabana Azmi, head of jury this year, joins them and gushes about how much a fan she is of Mohsen’s cinema. She descends on Samira, asking her father if she speaks English too. Another session of praising-to-the-skies follows. “The press is going to hound you in India,” she tells them. Mohsen looks at this correspondent with a twinkle in his eye. “We’ll talk in the car,” he says in his heavily accented English.

The Makhmalbafs are not new to India, you learn as the car speeds towards the venue of the festival. Samira’s film, At Five In The Afternoon, won the Best Asian Film Award at the International Film Festival of India (IFFI) in New Delhi last year. Makhmalbaf himself has been part of juries at previous IFFIs. “I’ve been here four times. The first was 15 years ago,” he reminisces.

|

| A scene from the film The Day I Became a Woman |

But this time, he has a bigger purpose. It has been one of Mohsen’s greatest wishes to make a film here. “I wrote the script 15 years ago, and this time, I intend to travel all over the country to get the locations in order,” he reveals. He hasn’t zeroed in on a name. But it will be on the different cultures, of India using real people as actors. “I may use one or two from Bollywood too,” he tells you as an afterthought. The movie, if he directs it, will mark his return to direction after almost three years.

Mohsen is also here to do what he does best — create new filmmakers. As part of the Berlin Film Festival’s talent campus, which Cinefan is a collaborator of, he will select the best of 50 one-minute films submitted by budding directors from all over India. The chosen ones will then get to discuss their films and hone their skills with Indian masters like Adoor Gopalakrishnan, Aparna Sen, and, of course, the great man himself.

At a time when Iranian cinema was becoming famous all over the world through the films of Abbas Kiarostami, arguably the country’s most famous filmmaker to date, Makhmalbaf brought in an alternative voice. Most film buffs equate the Kiarostami-Makhmalbaf debate with that of Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak. Makhmalbaf, they say, is the Ghatak of the story, the introspective, personal filmmaker who uses melodrama as a birthright, as opposed to the politically articulate Kiarostami’s neo-realism.

But while he’s seen Ray’s films “several times” and perfected the pronunciation of Pather Panchali, Ghatak remains unknown to him. “Where can I get his films, with subtitles?” he asks, after telling Maysam to make a note of Ghatak and his films. He plans to visit Calcutta this time. And Ghatak will definitely be on his mind, he says.

The director’s life could put a Bollywood masala movie to shame. Makhmalbaf had a disturbed childhood and was raised by a religious grandmother. He had 13 different jobs by the time he was 15. He was training to be a cleric when he joined an Iranian underground group called Balal Habashi. In 1974, the 17-year-old Mohsen was arrested for trying to disarm a policeman.

Prison made a different man out of him. During his training as a cleric, Makhmalbaf looked at religion from a social perspective. Prison made him look at it ideologically and philosophically. “They shot me in my hip at the prison. My body has many scars from the wounds that I incurred during my four-and-a-half years there,” he says.

The same Makhmalbaf who would cover his ears when he passed by a music store and considered setting foot in a cinema hall a sin, now struggled to find a means of expression for all that was pent up in him. He admits that as a cleric-in-waiting, he looked upon truth as absolute, like a reflection in a mirror. As he started making films, he realised that truth was a combination of all the images that are reflected from the pieces of a broken mirror. “I tried to find a connection among all the images,” he says.

Makhmalbaf was released after the Shah’s regime fell in 1979. Iranian cinema was going through a whole gamut of changes then. The flourishing industry had to contend with a more stringent code of conduct. There were dos and don’ts to deal with. Cinema from other countries being banned, there was no Hollywood to draw inspiration from. But repression has strange ways of bringing out art in men.

“I realised that nothing had changed since the Shah’s regime. Things had only got worse. I decided to bring in my own form of revolution. I tried to change the people’s minds through my cinema. Initially, I was only bothered about the Iranians. But with travel, I realised that other cultures, especially the Afghans, needed their own voice of expression,” he says while talking about his concerns with the three million Afghan refugees in Iran, whose cause he has taken up.

His films are surrealistic. A critic, after watching his film, Kandahar, said, “It is either a stunningly incompetent film or an amazingly evocative one.” And there is always a bigger story to the story that is being said. For example, in Cycleran, or Cyclist, released in 1987, an Afghan man has to ride a bicycle for seven days non-stop in a one-act circus to collect money for his wife’s treatment. The one-act circus was representative of the desperate Afghan in the Taliban regime, who would do anything to stay alive.

After making sure that his success was as huge as his name difficult to pronounce, he has gone on to create what may be the world’s only dynastic genre of filmmaking. In his family of five, each one is an acclaimed filmmaker. And his directorial school, Makhmalbaf Film House, will make sure there are more.

Makhmalbaf certainly has been as radical with his cinema as his children’s upbringing. Aruna Vasudev, film critic and festival director of Cinefan, who was bowled over by the director’s treatment of two of his films, Time Of Love and Nights Of The Zayandeh-Rood, in 1991, says, “I was head of the jury at the Iranian Film Festival that year. These two films (both banned in Iran even now) made me think, ‘This guy’s a genius’.”

His film Gabbeh was nominated for the Oscars. And many who went to watch his Nassereddin Shah Actor-E-Cinema (Once Upon A Time, Cinema) thinking an Indian actor might have featured prominently in it, came out richer with the knowledge of Iran’s incredible film history and a ruler who wanted to be part of it.

That’s the father. Daughter Samira Makhmalbaf is certainly one of the most talented among the current crop of Iranian filmmakers. At 18, she became the youngest director to have her film showcased at the Cannes Film Festival. Vasudev has some vivid memories of 1998. “I just saw her hanging around with her dad at Cannes. Even at that age she was very confident.” However, ask Samira about how much her dad helped her with filming, and she goes on the defensive, “He helped me, but I direct my own films,” she says, curtly.

Making them think for themselves is probably the reason why he decided to pull his children out of school one fine day and enroll them in his film school. Samira, who was pulled out of school at 14, is none the worse for it. Her first film, The Apple, went on to be screened at 200 film festivals worldwide and appreciated for its uniqueness. Although there is too much of her father in the film (he wrote and edited it) for it to be really hers.

Marziyeh, Mohsen’s second wife and the sister of his first who died in a fire accident, has some wonderful films to her credit too. The Day I Became a Woman is known for its imagery, and a scene with hundreds of burqa-clad women riding bicycles is one of the most poignant images of freedom as they come. Younger daughter Hana’s documentary, The Day My Aunt Was Ill, was screened at Locarno when its director was all of eight. Son Maysam has made a documentary on how Samira made her second film, Blackboards. Makhmalbaf is not a success story himself, he is a creator of success stories.

Take him if you want, or leave him. These lines that he wrote while critiquing the demolition of the Bamian Buddha are a case in point: If you read this article carefully, it will take about an hour of your time. In this very hour, at least 14 more persons will have died of war and hunger in Afghanistan... If these bitter issues do not apply to the happiness of your private life, please don’t read it. That’s not just the way Mohsen Makhmalbaf writes.

That’s the way the Makhmalbafs make their films, and lead their lives. That’s the way they are.