|

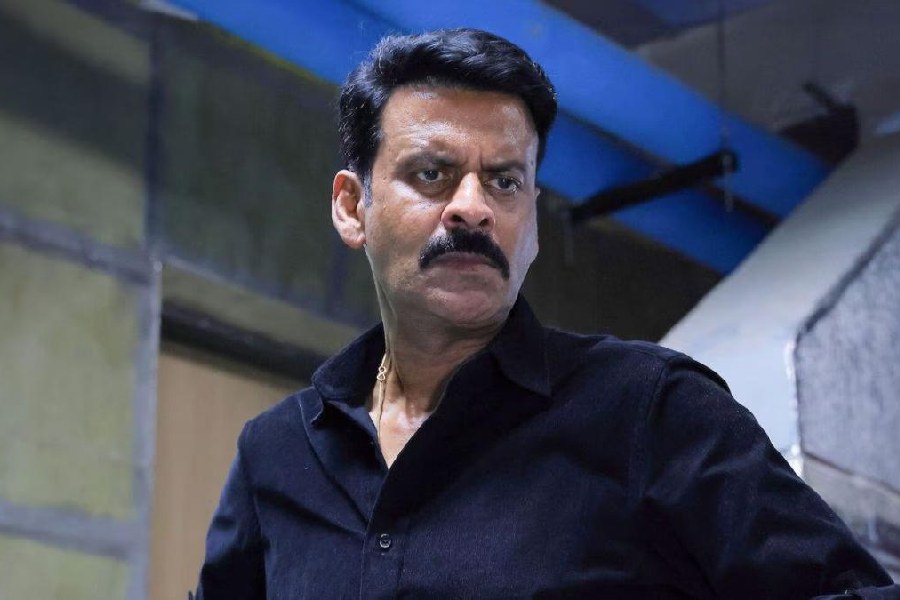

| OUT OF THE CLOSET: A scene from My Brother Nikhil (above); Cover of the book launched last week |

|

No, I will not marry a woman because I am gay and in love with a man and, no, I will not shut up, because I have a voice. Whip out the leather, the necklaces, the pink glossy lipstick, then, and take that man’s hand and walk down Camac Street, and if you die in the process, it’s better being dead than actually living a compromised life.”

Sometimes, a little bit of noise helps work wonders. And ever since the Deepa Mehta film Fire ? starring Shabana Azmi and Nandita Das as lesbian lovers ? hit Indian theatres to extreme reactions in the mid-Nineties, stray voices demanding the legitimisation of same-sex love in India were often heard, though few of them registered in the public consciousness.

Of late, however, the winds of change seem to have started blowing. And the noise has begun to gain in decibels, moving out of the closet and on to the streets. Being gay, it appears, is no longer what it used to be, and many are proud to say that for themselves.

Consider the opening lines, an extract from an essay in a book titled Because I Have a Voice: Queer Politics in India released in Delhi last week. Editors Arvind Narrain and Gautam Bhan call the book with 27 articles the first organised literary effort on the part of the gay community to assert itself in a world which still sees same-sex love as ‘queer’.

“It’s a collective voice that demands change, starting from within one’s own family and extending to a greater social circle,” says Bhan. “It’s also a statement on behalf of those who still don’t have a voice of their own, owing to social, cultural or linguistic barriers.”

The contributors to the anthology come from within the gay community, and hail from distant corners of the country. There’s even an essay by Sandip Roy, a gay-rights activist based in the US, which compares the way alternative sexuality is perceived in India and the US. Treading their respective walks of life, most of them are intensely involved in the gay-rights movement ? while Chayanika Shah is an active member of organisations such as Lesbians and Bisexuals in Action and Forum Against Oppression of Women, Revathi is currently documenting the lives of eunuchs in the country.

However, the joint literary effort by Narrain and Bhan is definitely not the first of its kind when it comes to exploring issues related to same-sex love. Over the past few years, books relating to ‘queer’ politics in the country have routinely made appearances in the Indian literary sphere.

Same-sex Love in India: Readings from Literature and History (2000), edited by Saleem Kidwai and Ruth Vanita, Man Who Was a Woman and Other Queer Tales in Hindu Lore (2001) by doctor and mythologist Devdutt Pattanaik (who has also contributed an essay to Because I Have a Voice) and Queering India: Same-sex Love and Eroticism in Indian Culture and Society (2002) by Ruth Vanita happen to be some of the better-known texts to this effect. Clearly, the stage had been set for a collective effort, that Bhan and Narrain eventually managed to pull off.

Kidwai, a historian and an advocate of gay rights in India, thinks these are indications of the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) community making its presence felt in India. “Even five years ago, it was virtually unimaginable to launch a book that dealt with same-sex relations in the heart of the city with such fanfare,” he says of the glitzy release of Because I Have a Voice at a Delhi bookstore. “Also, identifying oneself as gay and then writing on behalf the community was not something many dared to do. But now that things have been set in motion, it will only encourage more and more people to come out of the closet and assert their rights in society.”

The motion that Kidwai speaks of is evident not only in literature but in other media as well. While Bangla rock band Cactus belted out their track Pegasus in support of the gay community a few months ago, the 2005 Bollywood production My Brother Nikhil dealt rather poignantly with a script that had as its protagonist an ace swimmer, who happened to be gay and was HIV positive.

Such developments, say activists, are complemented by the fact that ‘coming out’ for members of the gay community has never been easier. And a major boost to this effect, feels Calcutta-based activist Pawan Dhall, is the fact that social acceptance levels are gradually on the rise. “Middle-class India is slowly coming to terms with alternative sexuality,” he says.

To illustrate his point, Dhall cites an example from his own life. After participating in a gay-rights rally in Calcutta last year, Dhall says he was approached by a neighbourhood storekeeper, who had seen him grow up in the vicinity but had never conversed with him over anything more than routine buy-and-sell over the counter. “He came up to me and said he had seen me on TV,” says Dhall. “He then congratulated me and told me to keep up the good work,” Dhall says.

With the arts having shown the way, it may not be long before the law of the land follows suit. “The Supreme Court has upheld our appeal to review Article 377 of the Indian Penal Code [that penalises same-sex relations], and we are hoping that the outcome would be positive,” says Anjali Gopa-lan, director of Naz Foundation, an organisation long- devoted to gay rights in India.

If and when that happens, it would perhaps be the day when the noise, in Dhall’s words, would lead to a profound silence of understanding. And that, as he says, would definitely be more welcome than the silence of ignorance.