|

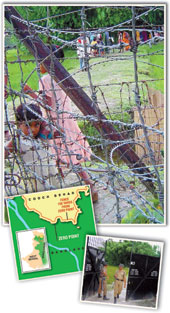

| FENCED OUT: Children in the village of Karala (top); Border Security Force jawans (above) |

Mallika Khandekar is the first to arrive and last to leave her school. Not that she has any choice. Unlike other children who can go to school freely, Mallika, who lives with her parents and brother in a fenced-in village along India’s border with Bangladesh, is shackled to a timetable set by the Border Security Force (BSF).

The gate to her village ?and home ? opens at 10 in the morning, a full hour before school begins. When her school ends at 1 ’clock, she doesn’t leave for home. The gate opens for the second time only at five in the evening.

She stays behind, tired and famished. On days when she can’t bear the gnawing pangs of hunger, she plods into the woods and vents her anger on the fallen twigs, picking them up and smashing them into pieces. This often helps her calm down, but leaves her soft palms bloody.

The going is tough, but Mallika bristles when her classmates suggest that she ask her parents to leave their village on the other side of the barbed wire fence and move to what they call “free” India.

“If we were not poor we would have moved away a long time ago,” says the 11-year-old fifth grader at Nayarhat High School, her voice cracking. In fact, given a chance, all residents of Karala ? Mallika’s village in Bengal’s Cooch Behar district? would have done that.

A human rights crisis is brewing along Bengal’s 2000-km-long (and in places porous) border with Bangladesh. More than 1,00,000 people living in scores of villages such as Karala have virtually been cut off as India builds a fence some 150 yards inside its territory to stop illegal immigration and smuggling.

For the villagers, cooped up in between the BSF on one side and the Bangladesh Rifles (BDR) on the other, life is fraught with danger. A stand-off between the BSF and BDR over anti-erosion work and

fencing in the Malda district of north Bengal led to a confrontation last week. BSF jawans fired more than 1,000 rounds in an exchange of fire with the BDR. And though the firing has stopped, the area remains tense with both forces on high alert.

These villages lie between what is known as Zero Point (the actual Indo-Bangla border) and the eight-foot-high, barbed wire fences being erected on the Indian side.

Villagers live at the mercy of the BSF, which opens the gates built in the fence to let them into their own country only three times a day, each time for an hour.

The villagers ? mostly farmers with small plots of land ? complain of being regularly searched, harassed, abused and even beaten up by BSF personnel, who they say fail to tell them from the Bangladeshis. Even buying essentials like oil, salt and sugar from the markets in the mainland is a problem. The BSF men often accuse the people of smuggling, and stop them from taking groceries into the villages.

And that’s not all. The villagers are also often at the mercy of the Bangladesh border guards, who pick them up at the slightest opportunity, accusing them of spying for India.

“The Indian government has simply abandoned these people. They have nowhere to go,” says West Bengal agriculture minister Kamal Guha, a senior leader of the Forward Bloc. He says the fencing has also wrecked the economy of the villages and ripped families apart. “Their relatives find it difficult to visit them, and nor can they go and meet them at will,” Guha says.

None of the fenced-in villages has electricity and few have drinking water. Muftaza Hossain, a state electricity board employee who lives in Karala, says electricity to the village was disconnected after the fences were erected about five years ago. “They said it was not permitted anymore.”

The fencing has bisected several villages, putting drinking water beyond the villagers’ reach. “The tube wells are all on the other side of the village, but we can’t go there now because of the fence,” says Afzal Hossain of Khitaberkuthi II village in Cooch Behar’s Dinhata subdivision.

The sick suffer the most. When Afzal Hossain’s wife, Aasna Bibi, was struck by diarrhoea one afternoon a few months ago, he wanted to take her to hospital, but the BSF jawans wouldn’t open the gate. “Only God saved my wife that day,” he says.

It can get worse at night. After Shaidul Khandekar’s 10-year-old son started vomiting one night last year, he went up to the gate and yelled for the border guards to open the gate. Initially, he says he was showered with a volley of abuses, but the guards later took pity on the child and let them out so they could go to a doctor.

“We have been living in a prison since this fence was erected. Sometimes, we wonder whether the government considers us Indian citizens at all,” Khandekar says, flashing his voter’s identity card issued by the Election Commission.

Muftaza Hossain wonders, too. For the first time in his life, he had to miss the early-morning flag-hoisting ceremony on August 15, because the BSF wouldn’t open the gates till 7 am. “Who says you are citizens of a free nation when you are not allowed to raise your country’s flag?” Hossain, 56, asks, a trace of anger in his voice.

Anger is palpable in the “prison-like” villages, where few dare to dream. Rashida Bibi, of Khitaberkuthi II village, is an exception. She got her five-year-old son Mustafizan into an English medium school at Chowdhuryhat last year by pawning her gold bangles as she wanted him to be “a somebody” when he grew up.

But the mother was shaken when the BSF jawans would not let her son back into the village after his school ended at noon. The small child was kept waiting at the gate till 5 pm. “I went up to the gate and pleaded with them, but they said it was not a door to my house that would shut and open whenever I wanted,” Rashida Bibi says.

She took up the issue with the local panchayat, which intervened and had the BSF issue “special permission” for the child to get back home at noon. “But even now, I can’t take my son out in the evening for English lessons,” she says.

Things have come to such a pass that the young men and women can’t find marriage partners, as few brides or grooms from outside are willing to venture into these fenced-in villages, let alone spend their lives there.

For the last two years, Mamoda Bibi has been trying to marry off her daughter, Abiya Khatun, but without success. “Not once, but twice, the parents of a groom whom we had chosen from a village on the other side of the fence had come to see my daughter. They were not allowed in,” the woman says. The groom’s family went back swearing never to return.

Sure, those who could leave the fenced-in villages have done so. But most are too poor to leave their homes. Land prices, too, have crashed in the villages, making it difficult for most to sell their land and move away.

But S.R. Tewari, inspector general of the BSF’s north Bengal frontier, says the fence has “stemmed the tide of illegal immigrants from Bangladesh and reduced smuggling”. In any case, the BSF, he says, “tries its best” to help the villagers by relaxing the gate timings for schoolchildren and the sick.

Actually, India is on the point of wrapping up its decade-long work on fences along much of its 4096-km-long border with Bangladesh. In north Bengal, for instance, fencing has already been done, covering 635 km of the total 782-km border areas identified.

At the core of the problem, BSF officials say, is an international convention that prohibits any construction “with defence potential” along an international border, prompting India to build the fence 150 yards from the border.

But unlike Punjab’s border with Pakistan, where fencing has already been done, areas along the border in Bengal are densely populated. “In Punjab, there are only farming fields, no villages. So people there go to the fenced-in areas along the border to farm. Nobody lives there,” a BSF assistant commandant says.

A CPI(M) source says chief minister Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee, aware of the plight of the people in the cut-off villages, has taken the issue up with Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. But the move may have come a bit late in the day as most of the fences have already been built.

The only option left to the country, administration officials say, is to relocate the people living in these villages. “But where is the land and who’s going to pay for relocation?” asks Gobinda Roy, Forward Bloc MLA from Jalpaiguri, where several such villages are located.

That’s the 2,000-km question. And until it’s answered, a weary Mallika Khandekar will have to stand outside a locked gate for hours before she can come home from school.