|

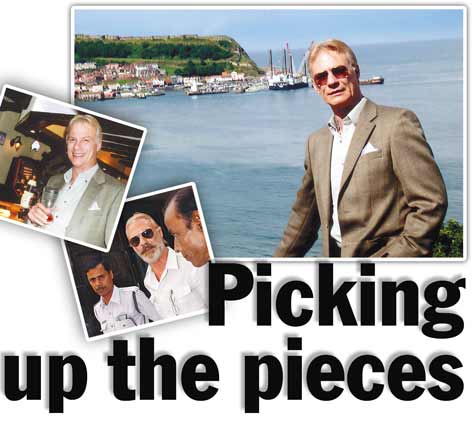

| A NEW CHAPTER: (Clockwise from bottom) Peter Bleach at Bankshal Court, Calcutta; chilling out at a pub in Scarborough, England; at the harbour there |

The man who met me at Scarborough railway station is a household name in Calcutta. The navy-blue blazer and tie had been replaced with a light brown jacket and an open-necked white shirt. But the trademark Ray-Ban glasses and white handkerchief peeking out of the breast pocket were still very much in place.

The six-foot-tall, blond Englishman who walked towards me with his arm stretched out in a handshake was none other than Peter Bleach — the kingpin of the mysterious Purulia arms-drop which shook India in 1995.

Looking every bit of the public-school boy that he is, he warmly welcomed me to his home town in Yorkshire with a “so glad you could come” in a ‘pucca’ Indian accent. This was just the first of many lasting impacts that India, and Calcutta in particular, have left on the 53-year-old Brit.

As we walked towards the blue Mazda parked in front of the tiny railway station, he turned to me and said “I am overwhelmed that someone has come all the way from Calcutta just to meet me. Thank you so much for coming. I thought India had forgotten about me.”

But how could anyone forget about the gunrunner who was branded India’s Criminal No. 1 and international terrorist by the Central Bureau of Investigation? The former British army soldier narrowly escaped the gallows but rotted for nine years in Presidency jail in the heart of Calcutta before he was unexpectedly released in February by the Indian government.

Driving through the tidy, sleepy coastal town of Scarborough with the warm summer sun falling on his pink, smiling face, Bleach looked as if those nine years behind bars could have just been a horrible nightmare, nothing more. But they were real and they have left their scars as I was to find out in the course of the day.

We pulled up in front of an old Victorian pub a stone’s throw from the scenic harbour and parked the car. Suddenly, the smile on Bleach’s face vanished. And he pleaded: “Please don’t name the pub in your article. There are many in India and England who would like to silence me forever because I know too much.”

I followed him, through a side entrance and up a flight of stairs. Half-way up, he turned and said, “Can you imagine I forgot how to use stairs, as the only steps I climbed for nine years were those at the Calcutta High Court the few times I was taken there.”

“We take so many ordinary things for granted. You only realise how important they are when your freedom is gone. One of the things I missed most in jail was walking in the Yorkshire moors on cold winter days with the wind howling around me,” he said opening the door to his tiny flat.

“Do you walk now?” I asked. “Oh very much so,” came the enthusiastic reply. “My fiancee, Elizabeth Boyle, and I love going for long walks, and I cherish them all the more, having lost them once.”

The small but neat apartment has two rooms. The largish living room with an open-plan kitchen on one wall and a makeshift study on the other. Beyond a closed door is the bedroom — probably the one place where he can shut out the world and every bad memory.

He picked up a a tan teddy bear with a red ribbon round its neck from a sofa and started caressing it fondly. “It has been with me throughout,” he muttered. “All the dust of Calcutta has not been wiped away yet.”

The gunrunner is savouring his freedom, but time is at a premium. For Peter James Gifron von Kalkstein Bleach — even his name sounds straight out of a spy thriller — is grappling with two deadlines that give him no respite.

The publishers are demanding the manuscript of his explosive memoirs by the end of September. And on October 1, he is slated to get married for the fourth time in his chequered life.

“Elizabeth is a friend of my mother and we have been neighbours for over 20 years. And though this is going to be my fourth marriage, this time it is till death do us part,” said Bleach.

“At present, I am torn between my laptop and my future wife,” he joked with a twinkle in his eye. But for Bleach, the book is serious business. “My book will set the record straight. I am not a terrorist. I am a law-abiding citizen who was taken for a long ride by his own government.”

Bleach says the autobiography — he is already more than 35,000 words into the book, working eight hours a day — will expose the murky world of British intelligence, shady goings-on in the Home Office and the Indian government and the links between law enforcers and criminals.

Even as a jailbird, Bleach insisted that the arms-drop on December 17, 1995, took place with the full knowledge of the British and Indian governments — a charge which has never been fully refuted by authorities in either country.

Security experts say the strange case of Bleach has no parallels. They believe the tentacles of the international conspiracy Bleach was sucked into, knowingly or unknowingly, reached MI6 (Britain’s spy agency), the highest echelons of the Indian government and, possibly, the CIA.

The book, according to Bleach, will help him get across what he sees as the most critical point: that “the British and Indian governments had advance notice of a terrorist incident and didn’t do anything about it.”

“Nothing can replace the years I have lost,” he fumed. “It has been a long struggle since 1995 and I feel vindicated that the government of India decided to free me. In a sense, I have been absolved. But the full story must still be told.”

Life, for Bleach, will begin anew when the story’s been told. “My blood boils when I think of how badly Whitehall treated me. The British government, I’m ashamed to say, pulled out all stops to rescue a convicted paedophile like 1970s rock star Gary Glitter but left a patriot like me to rot in a foreign jail. Even if I am guilty of everything I was accused of, I have the moral high ground compared to that paedophile.”

Bleach struggles to pick up the threads of a normal life, but clearly, he nurses a few grouses. Before he was thrown into Presidency jail, he had 20-20 vision. But now, age and a bout of tuberculosis which was diagnosed late and not treated properly by prison doctors, have taken a toll on both his eyes and lungs.

Bleach also moaned the advance of technology. “So many things changed in my absence. The Internet revolution happened behind my back. Though I have been using the Internet for five months now, I’m still flabbergasted by its reach and speed. It’s spectacular.”

The clock on the wall struck two and Bleach jumped up, patted his tummy and said: “Time for lunch.” We went down to the pub and Bleach ordered two plates of fried haddock and chips. “As a Calcuttan, I’m sure you like fish,” he told me. “You may call me old-fashioned but I make a point of eating fish on Fridays.”

Fridays, in fact, hold a special significance for Bleach who revealed that he owes his life to the Muslim inmates of Presidency jail. “Earlier, I treated only Sundays as sabbath but now the Islamic Friday is as important to me.”

Bleach said that the Muslim prisoners secretly fed him when authorities denied him food at the beginning of his jail term. “It is not that Muslims condoned the crime I was accused of but they could not bear to see another human being starve. And they fed me at grave personal risk. There are far more conscientious Muslims than there are Christians. Both the Bible and the Koran tell us that we should not walk past a beggar if we have money in our pocket. Similarly, if we have food, we should not ignore a hungry man, no matter who he is. Unfortunately, most Christians only pay lip service to these instructions, whereas most Muslims put them into practice.”

Bleach is trying to repay his debt to the community by helping to build bridges between Christians and Muslims in Britain. He has even appeared on the BBC’s religious service with the Orthodox Bishop of York to remove misconceptions about Muslims.

“If I can do just a little bit of good to promote understanding between the two communities, then my time in jail will not have been wasted.”

Bleach has many stories about his time in prison. But the most rivetting is about a Presidency jail superintendent who went all the way to the British Deputy High Commission on Ho Chi Minh Sarani to cut a deal. He offered to look after Bleach in jail for a price but was shooed away by vice-consul Bernie Andrews.

Bleach believes Ananda Marg was a smokescreen — all the arrested Margis were ultimately acquitted — for a much bigger game in which the British, Indian and probably American governments had stakes.

“I could be wrong,” Bleach said, “but the operation had all the hallmarks of a CIA job — possibly one offering covert support to an Indo-British attempt to destabilise Myanmar by arming Kachin rebels fighting the military junta.”

As Bleach waved me goodbye, and the small train chugged out of the station, I was left wondering whether the real story of the arms-drop would ever emerge.