|

In many parts of arid Rajasthan, the man who drives the water tanker to any parched village is like a mobile god on wheels. With the wells having dried out and the crop of jowar and bajra on the verge of dying, the arrival of the water tanker or its absence is the difference between euphoria and misery.

But water tankers are often undemocratic and unjust entities. The amount of water you can take home depends on the number of vessels you have. And often the water forcefully juts out of the hose and falls vainly on the parched earth. In eastern Rajasthan, where women often trudge 10 km or more for a pitcher of water, that’s a crime — if not a sin.

There is one exception, though. In Lapodia, a village about 80 km south-west of Jaipur, nobody rushes out with pots and pans for the life-giving liquid. Unlike other villages in these parts, here the wells are full of sweet water and animals have plenty of green fodder to chew on. In an area where scuffles over water are routine, even passers-by in Lapodia are not refused a drink. Despite the rains last week, the spectre of drought still looms in Rajasthan. But like a gladiator well-prepared to fight an inveterate enemy, Lapodia is battle-fit to combat drought head on.

The miracle is man-made. Lapodia is neither blessed with a river running through it nor has a wonder pond that refuses to dry up. Instead, using rain water harvesting techniques, the village has carefully captured and preserved every drop of water inside its womb, much like a small girl saving money in her piggy bank. And scanty rainfall in five out of the last six years notwithstanding, these deposits are sufficient to let the village feed itself and its livestock. Few, if any, migrate to Jaipur for jobs or scrounge for food in the city’s drought-kitchens when the situation turns for the worse.

As you enter the outskirts of Lapodia, a signboard written in Hindi warns you: “This meadow is an open zoo. Here you don’t terrorise the animals, you don’t chop trees or bushes, you don’t encroach. If you do, you will be punished.” Driving closer to the village, the contrast with other hamlets in the vicinity grows starker. Madhopur, a neighbouring village, for instance, has no other tree to speak of but the viciously thorny vilayati babool — useful only as firewood. Lapodia, which literally means ‘crazy people’, has cleared its grazing fields of the vilayati babools; it has thousands of desi babools, neems, peepals, kairs and palms. These trees have turned the village into a natural bird sanctuary. Parrots, woodpeckers, sparrows, cuckoos and a host of other birds which only an orinthologist can identify, abound. Bird dropping is so high that rural folks fill them up in sacks and use them as natural manure.

At the heart of Lapodia’s metamorphosis — from a barren, sun-dried village just a decade ago to a land of trees, ponds and birds today — lies an indigenous system of preserving water, developed by native Laxman Singh. Put into practice in 1994, the system has helped this 200-home-village repair its dry ponds, recreate a meadow spread over 300 bighas for cattle grazing, raise the water table and keep its wells filled with water.

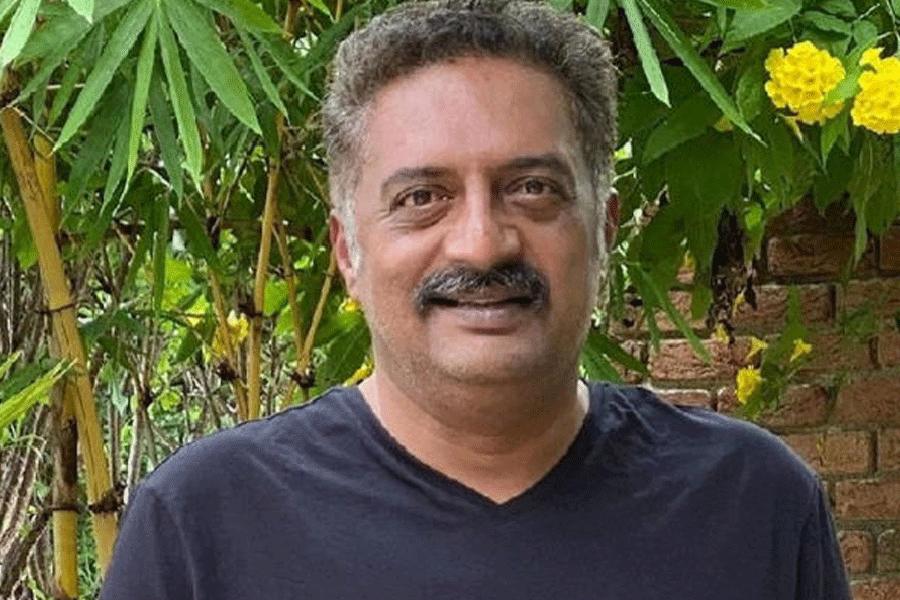

Singh, 49, is neither a hydro-geologist nor an engineer. In fact, he has never been to college. But he has dipped into the wisdom of traditional knowledge that helped folks in this parched land survive for centuries and harnessed it into a weapon that can outmanoeuvre drought.

In his youth, Singh left Lapodia, travelling to different parts of the desert state to observe time-tested, watersaving techniques that had slowly fallen into disuse, as well as closely looking at the ongoing state government schemes. “I had formed a small NGO, Gram Vikas Navyuvak Mandal, earlier. I came back to put my knowledge into practice,” says Singh. Shortly, he began experimenting with his ideas.

Singh first started repairing the village ponds. But soon he realised it wasn’t enough. A village survives as much on agriculture as on livestock farming. But Lapodia’s meadow, like most other grazing fields in the area, had already been destroyed due to years of degradation. Mobilising the entire village to create a meadow spread over 300 bighas wasn’t easy. Many felt it was actually a ploy to grab village land. But Singh managed the improbable.

The dividends are exceptionally good. Every day, the village sells 1000 litres of milk to the state dairy. Last year, the village sold Rs 24 lakh worth of milk. “Some years we have done better,” says Ram Karan, president of the village committee.

The Lapodia model is now being incorporated in state government schemes as well as by other NGOs such as the Catholic Relief Services, which had also helped out the village initially. Even other villages are trying to emulate its success story.

Some kilometres away, speaking in a husky voice from behind a veil, Krishni Bai tells you how her village Mahatgaon is learning from Lapodia. A village committee of 20 people periodically goes to the green village to learn techniques that could improve ground water tables. Drawing criss-cross patterns on the ground, she draws out an imaginary map of the water system which her own village has also adopted. “They can be equally successful. All you need is patience and discipline,” says Singh.

Lapodia is about the small and simple victories of ordinary people. It is not the kind of story that makes newspaper headlines but it is a real story of India shining.