|

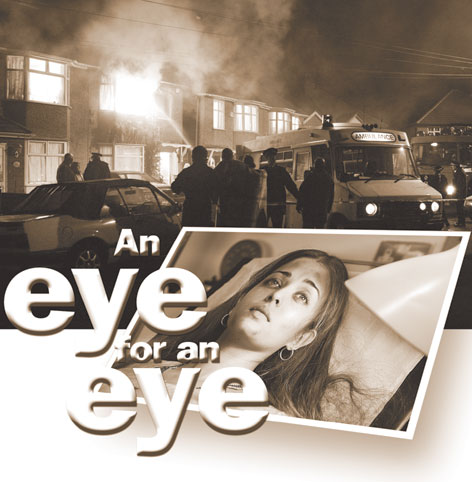

| Firestorm: A still from the film Provoked and (inset) Aishwarya Rai in the lead role |

When Aishwarya Rai finally met Kiranjit Ahluwalia, the Sikh woman she is portraying in the film, Provoked, the two women hugged each other. The director, Jagmohan Mundhra, had deliberately kept Aishwarya away from Kiranjit until the shoot was nearly over so that “Aishwarya does not subconsciously try to copy Kiranjit’s mannerisms.”

Back in September, 1992, Regina vs Kiranjit Ahluwalia made English legal history when Kiranjit was released after serving three-and-a-half years of a mandatory life sentence for murdering her husband, Deepak, whom she had drenched in petrol while he was asleep and set alight. Her retaliation followed 10 years of systematic abuse but what caused her to flip on that fateful evening was that he had pressed a hot iron against her ? she still bears the scars.

Kiranjit was released by Appeal Court judges on grounds of “diminished responsibility” but her case, taken together with those of other women, all white, who had also killed their partners, has helped bring about a change in the law.

Today, if a battered woman strikes back and kills her husband or partner, the “slow burn” ? the time period between the acts of abuse and retaliation ? is taken into account. Unlike a man, who is physically stronger and can instantly lash out in a moment of anger, a woman smoulders inside but often waits before she seizes her opportunity. The law previously construed this to be pre-meditation and found women guilty of murder but after Kiranjit’s case, the charge can be the lesser one of manslaughter ? which does not automatically carry the mandatory life sentence. It is a sobering thought that once upon a time, before the death penalty was abolished, Kiranjit would probably have gone to the gallows.

However, thanks to the campaign conducted on her behalf by the Southall Black Sisters, a women’s rights group in west London, and a dynamic young Indian lawyer called Rohit Sanghvi, English law, while not giving battered women a licence to kill their men, is a lot more understanding about their plight.

Kiranjit’s story has been fictionalised but it is broadly based on Circle of Light, her autobiography she wrote with Rahila Gupta, a long-serving member of the Southall Black Sisters. Rahila’s screenplay has been further dramatised by an American, Carl Austin, brought in by the director.

Kiranjit has mixed feelings about the film. Her sons, who were children, aged eight and six, when she was released, are today young men of 21 and 19. Their mother, who does a routine job and is trying to rebuild her life, does not want old wounds reopened.

Rahila, her friend and confidante, says: “She is very moving when she starts talking about it. She starts sobbing. It’s still very painful for her.”

While Kiranjit has decided not to get involved with the promotion of Provoked, Rahila might yet persuade her to attend its London premiere. Her position does have some parallels with the late Phoolan Devi, whose life was turned into the hit film, Bandit Queen, while she was still alive. At the time, Arundhati Roy took up the cudgels on Phoolan’s behalf, arguing that an exploited woman was being further exploited by “a movie made for entertainment”. But Phoolan, who had a cunning streak to her, changed her tune and ditched Roy once she’d been paid ?40,000 by Channel 4 (?80,000, according to some accounts).

The view of Kiranjit, who is a lot more principled, is summed up as: “I suffered so long in silence. The reason why I want to do the film is the reason I did the book ? to expose the culture of silence.” Kiranjit wants Circle of Light to be translated into Hindi, Punjabi and Urdu for distribution in India. Rahila insists: “She has seen the film script; she has given her blessings. From the Southall Black Sisters’ point of view, if Kiran didn’t want to do it, we would not have touched this film.”

Having a former Miss World play Kiranjit is a double-edged weapon. From all accounts, Aishwarya had to fight to get out of her abusive relationship with Salman Khan and may have had her own reasons for taking on such a role. Also Chokher Bali has encouraged her to be more adventurous and Mundhra says he has “deglamourised” her for the role of Kiranjit. There were several women in the Southall Black Sisters who campaigned for Kiranjit ? Rahila herself, Pragna Patel, a lawyer, and Hanana Siddiqui, its director. In the movie, they are represented by Radha, an activist played by the feisty Nandita Das.

Nandita says she accepted because “it is supporting something that I believe in. Secondly, Jagmohan is someone I have worked with and for him it is almost like a trilogy of Kamala, Bawander and Provoked.”

She describes the character of Radha as “not a stereotypical activist character because when he told me, (I thought), ‘Oh, my God, it’s stereotyping me, a typical jholawallah, angry, activist.’ It is a little more layered than that; she has a lot of spunk. There is a lot of sense of humour about her.”

Provoked’s cast is impressive. Kiranjit’s violent husband, Deepak, is portrayed by Naveen Andrews (last seen in Bride & Prejudice). When Mundhra was shooting a wedding scene in a gurdwara, there was an attempt to stir up dissent among some Sikhs but it failed when even Aishwarya rallied to the director’s defence and said no disrespect had been shown to the religion.

Among British actors, Miranda Richardson, is cast as Veronica Scott, one of Kiranjit’s cellmates, who gets her estranged step-brother, Edmund Foster, QC (played by the distinguished Robbie Coltrane) to take up the Sikh woman’s case.

The plot remains a sensitive issue because no doubt some Punjabi men will take the film to be an indictment of Punjabi culture and fail to recognise that domestic violence remains a cancer which demands drastic surgery ? and not just among Asians.

It so happens that on the very day when Kiranjit was released in 1992, I asked the Southall Black Sisters, who can be very prickly about male journalists, whether I could meet her. To my surprise, they said yes. I did not know who was the more nervous when within an hour I was ushered into a little room to chat with Kiranjit. She was quietly understated but in an act of defiance, she had cut her hair short, adopted a trouser suit and abandoned the salwar kameez and everything that tied her to her previous oppressive way of life.

|

| Kiranjit Ahluwalia |

She had been a shy woman, even diffident about seeing an English doctor on her own, she explained. But in prison, she had matured and become a stronger person. When her marriage was in trouble, she had received no practical help either from Deepak’s family, who shut their eyes to his escalating violence, or her own, who suggested it would dishonour the family to seek a divorce.

She kept a Guru Granth in her cell, learnt English, typing, hair dressing and began a fashion course. “Why me, God?” she’d ask. “I have never hurt anyone before in my life.”

From prison, she wrote to her mother-in-law in Punjabi: “Deepak did so many sins, I gave him a fire bath to wash his sins. I did a prison pilgrimage to wash my sins.”

“I do have regrets,” Kiranjit told me. “I regret his parents have lost their son, that his brother has lost a brother. When my children are older I will try to explain to them. I regret they won’t ever see their father again.” Thankfully, her sons remain close to her. They, too, will have mixed feelings about the movie.

As to how much domestic violence still exists, Rahila says that the figures need to be interpreted with caution since women are less reluctant to come forward but “we have 2,000 cases and inquiries per year and we used to have about 1,000 in the early Nineties”.

During pre-production, Mundhra did his own research on domestic violence. “I was shocked at how widespread it is,” he confesses.