|

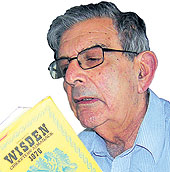

| FOND MEMORIES: Dickie Rutnagur |

After covering more than 300 Test matches over a period of nearly 60 years, Dickie Rutnagur is at the age of 74 preparing to take off his pads, journalistically speaking.

The sunlight is flooding into his small but neat London flat, filled with a full set of Wisden, the cricketing Bible ? and his memories.

It is sad to hear the doyen of cricket reporters remark: “I am on a low. I realise my working life is virtually at an end. Physically I am not able, my eyesight is going.”

The reality, one hopes, will turn out to be different. Even on his days off, his idea of relaxation is to go and watch cricket. There is probably no one with his encyclopaedic knowledge of Indian cricket or his ability to file accurate match reports on time.

He is planning to take his son, Richard, a former Oxford Blue, and grandson, Joshua, to Lord’s for the first day of the Ashes Test between England and Australia on July 21.

“My hair still stands on end when I go through the Grace Gate after all these years,” he reveals. “It is a privilege to go to Lord’s. I will wear my best clothes to go to Lord’s always, even for a county match.”

|

| Sourav: Nobody could impose an inferiority complex on India while he was captain |

Rutnagur was born in Bombay on February 26, 1931, and attended St Xavier’s College, where he came under the influence of Russi Modi, the former Test player, who told his impressionable prot?g? about cricket in England. In 1966, Rutnagur arrived in England, with an agreement to work every day during the summer covering county matches for The Daily Telegraph and then disappear abroad for the winter for Test matches.

Anyone who suspects Rutnagur has reservations about one-day cricket would be right. “That is one thing I do not like about modern cricket ? the partisanship and jingoism that goes with it and that has been bred by one-day cricket and the bloody tabloid newspapers although the heavies have also fallen into the trap now.”

“Bloody” is probably Rutnagur’s favourite word to denote disapproval, along with “bastard”.

He is not a Luddite. “What the game has lost is its dignity to some extent with the coloured clothing and all the trappings of one- day cricket. Commercialisation has come in and it has damaged the image of cricket in eyes as old as mine. But it had to come for the survival of the game.”

He argues that heavier bats have affected backlift and eradicated the age of “very elegant players” such as Mushtaq Ali, C.K. Nayudu, Frank Worrell, Tom Graveney, Rohan Kanhai and Alvin Kallicharan.

Rutnagur has a unique perspective on cricket, partly because he has been writing about the sport for so long. In his time, he has reported for many papers in India, the Gleaner in Jamaica and achieved quite a bit in broadcasting as well.

When the Indian captain, Nariman Contractor, was nearly killed in the India-Barbados game in 1962 by a delivery from Charlie Griffith, “I was on air,” remembers Rutnagur. “You could see blood coming out of his ears, one of the most ghastly sights I have ever seen.”

|

| Sunny & sachin: If I were to pick a batsman to play for my life, between the two I would choose GavaskarSourav: Nobody could impose an inferiority complex on India while he was captain |

|

Those were pre-helmet days and Contractor never again returned to Test cricket but he became firm friends with Rutnagur.

“He’s very dogmatic, very foul-mouthed, I’m very fond of old Nari,” grins Rutnagur. “He was a witness at my wedding on my wife’s side. My first wife was West Indian. Doris was the hostess on our flight from Trinidad to Jamaica. Her father wanted Contractor to be the witness at our wedding in Bombay.”

The Nawab of Pataudi, although only 21, succeeded Contractor as captain, although he had elected not to play in the first two Tests and confront the West Indian fast bowlers.

“He said he was injured. I don’t think so,” reflects Rutnagur, who had seen an energetic Pataudi at a party on a rest day. “Pataudi climbed up a huge tree like a monkey to hide somebody’s slipper up there to play some kind of a practical joke. He has always done daft things.”

Rutnagur’s assessment of cricketing ability has always been fair. “If he had not lost his eye (caused by a car accident during his Oxford days), he would have been one of the two greatest batsmen of his time, the other being Sobers.”

Once, before Pataudi’s accident, he had seen the youngster field at cover in a match between Delhi and Railways immediately after arriving from London. “They talk of (the South African) Jonty Rhodes but he was Jonty Rhodes’s grandfather.”

He also remembers Sharmila Tagore and Pataudi coming to his hotel room in Calcutta for drinks. She had been introduced to her future husband by M.L. Jaisimha, one of Rutnagur’s closest friends.

“She was one of the prot?g?s of Satyajit Ray,” emphasises Rutnagur. “She was very much a Calcutta girl. I have a lot of respect for that lady.”

Rutnagur has never gone in for celebrity stories about the cricketers he has covered, then or now, but he has strong opinions.

“I would say Sachin is India’s greatest ever batsman but if I had to pick a batsman to play for my life, between the two I would pick Gavaskar and, all time, if I had to pick an Indian batsman to play for my life I would pick Vijay Merchant,” he says.

He has a cordial relationship with Sourav Ganguly. “You can see he is very arrogant. It’s worked to India’s advantage to some extent ? nobody could impose an inferiority complex on India while he was captain but he has lost goodwill at the same time. Taking off his shirt at Lord’s was a very childish thing. That’s no way for a captain to behave.”

He finds Rahul Dravid, Ganguly’s possible successor, “an intelligent, well-bred, well-educated man, very sophisticated person, very nice person, very straight. Greg Chappell, the new coach, is talking in terms of Sehwag, I hear ? I don’t think that’s a good idea.”

He had great affection for the two who passed away recently ? Mushtaq Ali and Eknath Solkar. When Mushtaq came for an awards ceremony in London in 2002, there was a black tie dinner at Lord’s. “That was the first time since he played in 1946 he had come to Lord’s and he still walked up the stairs to the dressing room to see his old place without even touching the banister at the age of nearly 90, erect as a guardsman.”

Rutnagur had once tried to obtain a helmet for Solkar after the all-rounder had been hit on the head in the West Indies in 1976 but he backed off when the Indian team management warned him, “Don’t interfere in this business”.

One former dignitary about whom he retains a poor opinion is “Vizzy”, the Maharajah of Vizianagram, who sought to undermine the young Rutnagur’s prospects of a burgeoning career as a radio commentator.

Rutnagur confesses he “hated him. We were not on speaking terms except to hurl abuse at each other.”

|

| Tiger: If he had not lost his eye, he would have been one of the two greatest batsmen of his time |

Vizzy was in the habit of presenting tiger skins to visiting overseas cricketers, which provoked Rohan Kanhai, the West Indian (after whom Gavaskar, an ardent admirer, named his son) to ask him: “How do you kill these tigers?”

“I shoot them,” boasted the portly Maharajah. Whereupon Kanhai, according to Rutnagur, observed: “I heard that you leave transistors lying around and the tigers listen to your awful commentary and drop dead.”

Rutnagur now wants more time to listen to jazz and to his favourite composers, including Mozart, Rachmaninov, Tchaikovsky and Beethoven.

“I would say that cricket has been almost ? almost ? all consuming,” he agrees. “If I was a moneyed man and I could afford it, I would love to go around the world watching Test matches in the winter.”

Rutnagur wants the Ranji Trophy revived in India. “You know you need a strong base of domestic cricket and we had it in India and they destroyed it, the bloody idiots.”

At a personal level, he calls himself a Zoroastrian and not a Parsi because he alleges Parsis discriminate by not allowing other faiths into their fire temples in India. “Anybody who excludes anyone from a place of worship has to be bigoted. I can’t take you to a Parsi fire temple in Bombay.”

Perhaps Dylan Thomas’s, Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night, suggests there is fire yet in Rutnagur’s soul:

Do not go gentle into that good night, /Old age should burn and rave at close of day;/ Rage, rage against the dying of the light.