|

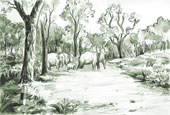

Illustration By Suman ChoudhuryThe Albanian seaside town, Saranda, is dotted with palm trees and the name is traced to a Greek word indicating the figure, ?40?. Curiously, closer home and barely 300 kilometres from Calcutta, we have our own ?Saranda? forest, the word said to indicate seven hundred peaks.

The land of seven hundred hills is spread over 820 square kilometres. Home to one of the densest sal forests in Asia, it still has stretches where sunlight fails to penetrate the canopy of trees. The stray vehicle is often forced to switch on headlights in the daytime and in autumn, there are stretches where one must wade through heaps of fallen leaves.

Parts of the forest have already been lost to iron-ore mining and dusty townships at Gua and Noamundi. The timber mafia have ruthlessly felled trees in other parts but the process appears to have slowed down after Maoists discovered the forest, on the borders of Orissa and Jharkhand, as an ideal sanctuary.

Saranda?s charm is enhanced by the Koel river that runs through it. The Tatas maintain a comfortable guest-house at Noamundi and the Indian Iron & Steel Company still has a majestic director?s bungalow, a white house, at Gua. But travellers generally make a beeline for Tholkobad, described as ?a patch of paradise on earth? perched at an elevation of 1,800 feet.

Around 45 kilometres from Manoharpur, travellers could once go across to Simlipal in Orissa, again at a distance of around 45 kilometres. But the quaint forest resthouse at Tholkobad has been burnt down by the Maoists and the forest department staff have fled.

The resthouse, built in pre-Independence days, had been preserved well, complete with the punkah and is missed by those who have had the pleasure of staying overnight in it. The fate of ?The Saranda Queen?, said to be the oldest sal tree with a circumference of 25 feet, remains unknown.

The forest has always sheltered a rebellious spirit. British administrators were fond of calling the region ?The Tibet of India?, so inaccessible and inhospitable they found the terrain. Invaders never dared cross it and in post-Independence India, the tribal inhabitants ferociously fended off the exploitation and corruption of government employees. They took recourse to administering the ?bhelua? oil, extracted from special plants, which virtually peeled off the skin. With herds of elephants, bears and the occasional leopard on the prowl, in short, Saranda was never the place for the faint-hearted.

Our first encounter with Saranda was during a jungle agitation. We had arrived late at Goelkera, where we planned to stay the night, but could not resist the temptation of taking a ride at night. We sat huddled at the back of a jeep, sandwiched between armed forest guards. The forest ranger sat stoically in the front, holding a double-barrel gun. There was little one could see in the darkness but one could make out the steeply rising incline on our left and the dark, cavernous slope on our right.

Suddenly, the jeep stopped with a jerk and the driver jumped out, swiftly ran ahead and lay prostrate on the ground. What?s wrong, we asked aloud, somehow breaking the tension. A herd of elephants, the ranger informed us, had passed that way and the driver was sniffing at the droppings and had put his ear to the ground in an exercise to ascertain the lapse of time.

If we came upon the herd, he quietly warned, the engine would be switched off and we should sit still and wait for the pachyderms to move away. ?But if they attack us, scramble down the slope.? The task appeared daunting enough and we barely suppressed our urge to scream at each other. Whose idea was it anyway to take the ride, huh?

The driver, meanwhile, rushed back beaming, and confided that the herd appeared to have passed an hour or two ago. But then there was no knowing where or when they would stop. The ranger instructed him to drive to the nearest forest resthouse. We must have covered some five kilometres before we stopped. The ranger sounded relieved and announced that we could step out for a cup of tea.

It was dark and the outline of a resthouse looked haunted and unreal. Soon we could hear the sound of water breaking into rocks and the stillness of the night. The old khansama lit a petromax lamp before serving us tea and biscuits. The bone-china crockery gleamed in the glow as the khansama gently, and proudly, informed that ?Guha sahib? from Calcutta often came visiting. Guha sahib turned out to be Buddhadeb Guha, the writer.

A year later, we were back in Saranda, this time at Tholkobad. Drawn by drum beats at dusk, we followed a trail and went down the hill. A group of villagers sat huddled around a fire. Most of them just sat there, drinking the local brew, a few danced.

As we edged closer, a woman began singing in her own dialect. But it was clear that she directed it at us, prompting some bemused looks. We pressed our escort, a forest guard, to translate it for us. And the lines were breathtakingly seductive. ?From wherever you have come, stranger/ It does not really matter/Let us drink and dance/ And if you feel like it, we can lose ourselves in the forest,? went the lines.

Forests are said to precede civilisations and deserts are said to follow them. As Saranda loses out to mining, export-earnings and politics, the songs of innocence, one suspects, have changed to more bitter lines. Was it a statesman who had said, only when the last tree has died and the last river has been poisoned and the last fish has been caught, will we realise that we cannot eat money?