|

A silver Skoda Octavia negotiates through the dusty lanes of Dharavi on a February afternoon, but Asia’s biggest slum barely bats an eyelid. A decade ago, a shiny foreign-made car would have made Dharavi turn its head. Today, as the huge swamp where the city once dumped its waste suddenly becomes Mumbai’s most precious real estate, a Skoda is just another car.

The man in the car is the principal agent of its change, one of the many construction czars who feel that Dharavi, located in the heart of India’s financial capital, is worth its stretch in gold. But not many had heard of Mukesh Mehta of MM Constructions till Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee announced a central aid of Rs 500 crore to redevelop Dharavi last month and eager politicians in an election year started singing paeans to the grit of Dharavi’s working class.

Mehta has no recognisable social worker credentials — no khadi kurta, no shoulder bag, no Kolhapuri chappals. Dressed simply in a pair of light green trousers and an off-white shirt, he looks like any other Gujarati businessman in Mumbai. “Beta, book my ticket in business class and also on the boat. The children will travel economy,” he says into his silver mobile phone. Mehta is organising a trip to Egypt for his family and staff.

So, what is an NRI who holidays in Egypt doing in Mumbai’s most notorious slum? He is in Dharavi, talking idealism. Formerly based in New York and now in Mumbai, Mehta is trying to implement an ambitious plan of redeveloping 174 hectares of land packed with slums and filth into a glittering township of parks, skyscrapers, shopping arcades and good life. “In the last seven years, I have made presentations to all possible players in this project. I must have had over 200 meetings with the people of Dharavi, with NGOs working here, with senior government officials. I have presented this plan to Manohar Joshi, to the chief minister’s office and even to the PMO,” says Mehta.

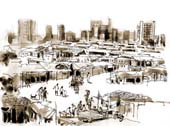

Dharavi is something of an alter ego to Mumbai, a sprawling slum in a packed city of high-rises. Not surprisingly, it has been an abiding symbol, at the centre of a great many cultural works. Sudhir Mishra used the image of Dharavi as quicksand in a feature film, while Naata, a documentary film by Anjali Monteiro, was based on a relationship between a Hindu and a Muslim in Dharavi during the communal riots of 1992-93. US-based film-maker Rajul Mehta’s Kumbharwada is on the potters of Dharavi. Journalist Kalpana Sharma’s book, Rediscovering Dharavi, was published by Penguin India in 2000. And when Prince Charles travelled to Mumbai, he chose to visit Dharavi.

Dharavi was once a swamp located between the islands of Sewri and Bandra, one of the seven islands that were reclaimed to create today’s Mumbai. Over 100 years ago, landless labourers from all over the country began to migrate to Mumbai and settled on this marshy land outside the original city limits. “In those days, the city’s main abattoir was located in Bandra near Dharavi, the reason why tanneries opened up there,” says Sheela Patel of the Society for Promotion of Area Resource Centres (SPARC). Potters from Gujarat came and set up their units in Dharavi, while many of the other residents worked at the Matunga central railway yard.

Post-Independence, the influx of migrant population increased rapidly. Like an eye-sore, Dharavi grew bigger and bigger as slum lords and political parties helped the proliferation. Today, according to official figures, Dharavi has 86,000 slum structures and 93,000 families living there with a mobile population of over a lakh people. The slum colony has an estimated 40 per cent of small scale industries manufacturing readymade garments, export-quality leather, pottery and plastic. Mehta pegs the annual turnover of Dharavi’s business at Rs 3,000 crore.

Mehta, who says he made his money in real estate in Long Island, New York, should know what he’s talking about, because he has been hired as a consultant by the Maharashtra government to implement the redevelopment of Dharavi at a cost of Rs 5,600 crore. The project titled ‘Dharam — a strategy for redevelopment of Dharavi’ envisages transformation of the slum colony into a modern township complete with housing, drainage systems, medical facilities, industrial units, schools, theme parks, cultural centres and sports complexes.

Mehta has divided the 174- hectare Dharavi land into nine sectors to develop residential, commercial, and industrial units. The Gems and Jewellery Institute has offered to take up one sector to set up the export-oriented institute.“This can create 50,000 craftsmen jobs for Dharavi residents. They can earn anything between Rs 8,000 to Rs 2 lakh per month,” Mehta says. He holds that Kangaroo Kids, an Australian education institute, has offered to set up schools to provide quality education to slum-dwellers.

On paper, the redevelopment plan promises heaven, but there is a fair degree of scepticism in the city about the construction industry’s sudden interest in Dharavi. With the construction boom of the Nineties, Dharavi’s real estate value shot up. Located at a 30-minute drive from South Mumbai and 20 minutes from the international airport, Dharavi connects the two arterial highways joining south to north Mumbai. “Its proximity to the Bandra-Kurla Complex which houses the diamond bourses and the financial sector has made Dharavi attractive to the construction industry,” says Magsaysay-award-winning social worker A. Jockin.

As the 2004 elections draw closer, political activity in the area has increased, too. Lok Sabha MP and speaker Manohar Joshi, who played a key role in acquiring funds from the Centre for the redevelopment project, is more visible than ever before. Chief minister Sushil Kumar Shinde emphasises the significance of the project in his public meetings.

It will be some time before the dust settles on Dharavi.