|

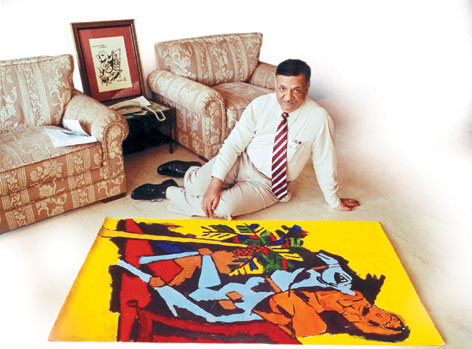

| Easel does it: The art investor with a Husain at his residence in Mumbai. |

If you believe him, buying Husains worth Rs 100 crore was a piece of cake for businessman Guru Swarup Srivastava. He settled the deal over a 45-minute meeting with the master painter at Gallops, the restaurant at Mumbai?s Mahalaxmi Race Course. What he finds more difficult is remembering the names of some other painters whose works he bought a month ago.

Now sitting in his plush flat on the sixth floor of Lokhandwala?s elegant Windermere apartments, where you see an Eminem-Kim Basinger poster in the music room but no painting and where a lone Charan Sharma Bundelkhandi hangs in the drawing room (?It is a gift,? he says), Srivastava is stuck on the name, Walter. Son Mehar helpfully calls someone up on his mobile. ?L.a.n.g.h.a.m.m.e.r,? he spells out the surname of the famous Austrian artist who had come to India to escape Nazi persecution during the Second World War. Even the surname of the Jehangir guy escapes him. ?Somawala,? he says hesitantly, referring to Sabavala.

Such slips of the tongue, though, are understandable from the hottest new buyer in the Indian art market who has no qualms in equating a piece of land with a canvas on oil, the difference only in the value of square inches. Having decided earlier this year he was going to buy paintings as ?a form of quick return investment?, the 51-year-old boss of the Swarup Group of Industries drove to a Mumbai art gallery and bought a platter of 18 paintings. ?I wasn?t sure if I had the negotiating skills in this new area. It was a test check,? he says. Like a consummate trader, Srivastava settled the deal for Rs 50 lakh whereas the gallery owner had initially asked for Rs 62.5 lakh. ?I also took 10 paintings for free,? he says with childlike glee.

But it was Srivastava?s audacious gambit of having clinched a Rs 100-crore deal for 100 Husains for a series, Our Planet Called Earth (OPCE), on September 9 that has sent the Indian art world into convulsions. The overall package is a little more complex. Srivastava admits that he wanted another 25 paintings for free but has settled for buying them at a ?much lesser price?. These paintings, he believes, will act as an insurance and subsidise the high-priced deal.

|

| M.F. Husain. Photos: Gajanan Dudhalkar / AFP |

In a country where the overall annual art market is roughly estimated at about Rs 300 crore and where even a Rs 30-lakh sale can make most painters smile, the deal?s magnitude is mind-boggling. Every aspect of the deal along with its after-effects on the Indian art scene ? the economics and the ethics ? is being widely discussed. There is an opposite view to every opinion. Some believe it is a landmark in the history of Indian art; others are sceptical about the figure being bandied about and believe that it is a gimmick to shore up sales.

The diverse views are understandable. For, Srivastava heralds the arrival of a new kind of art investor. Others at least claim to love art. But for him it is simply business.

Undeniably, in partnership with Maqbool Fida Husain, the Agra-born businessman who taught chemistry at a college, dabbled in radio journalism, compered for Doordarshan?s Yuva Manch before buying a rolling mill which produced aluminium sheets and finally made it big selling iron ore to Chinese government undertakings, has taken contemporary Indian art to the front pages of newspapers and prime time on television.

Art world insiders feel the unprecedented hoopla will also rub off on forthcoming Husain sales. On September 23, 12 Husains will be auctioned in New York?s Christie?s. And, a day later, Sotheby?s will open bid for more Husains. Pheroza J. Godrej of Cymroza Art Gallery feels the hype ought to help the sales. ?Everybody is Internett-ed,? she says. ?Such news travels fast.? But art dealer Vikram Sethi has a different take. ?People pay money for good quality. And the Christie?s collection is good anyway,? he says.

Many artists and art dealers believe that the deal will make more people think of art as investment and the ripple effect will benefit all Indian artists. ?Such an investment encourages both corporates and young people,? says artist Riyas Komu. Neville Tuli of Osian?s, an art auction house, too, believes that the deal has added excitement to the ?art as investment? issue. But, he warns, ?Only transparent market-driven processes have the credibility of bench-marking prices, everything else is a distortion which over time finds equilibrium.?

The deal has kicked up another debate: the age-old question of whether or not art can be seen as a commodity. Godrej believes that a commercial transaction is fine as long as it is not the only criterion for judging or appreciating art. Another school of thought stresses that art is on sale the moment an artist decides to let a work leave the studio and enter the free market.

But within the confines of the raging debates, the Husain-Srivastava deal has caused some raised eyebrows. ?There is something insensitive about the transaction,? says Godrej. Industrialist and art collector Harsh Goenka, too, feels that the deal is quite unusual. ?One usually buys a painting only after seeing it,? he says.

And since the deal was completed before a large part of the series was created on canvas, some in the art world wonder if it is worth the money. An art world insider questions why anyone would invest more than Rs 1 crore in a painting when several other Husains of similar sizes are available for a lesser price.

However, not everybody would agree with him. ?This is the correct price,? says the eminent artist, Laxman Shrestha, who believes that Indian paintings are grossly underpriced. And Dadiba Pundole, whose art gallery has been selling Husains since 1963, stresses that this is ?a new benchmark?. But, he adds, he is yet to sell a Husain for a crore of rupees.

But selling a work of art, as dealer Sethi stresses, is not the same as peddling soap or tea. ?A painter?s particular series becomes important for certain historical and intellectual reasons,? he says.

History, an art consultant points out, is full of uninformed collectors who have lost their money. A BBC documentary showed how many Japanese businessmen, who bought paintings of the Masters in the late Eighties with no knowledge of art or art market, burnt their fingers. ?One of them didn?t remember the name of a painter whose art he had bought,? says the consultant. The painter, incidentally, was the French Impressionist, Claude Monet.

Srivastava, however, has no such qualms ? for he is convinced he has a winner on his hands. The OPCE series, he holds, has become a brand name he can cash in on. ?I expect huge dividends,? says the businessman. And, he has great marketing plans. He intends to mount the OPCE series on velvet in China, the scrolls on silver.

He plans to give a signed and sealed lithographic version of the first OPCE series to the Queen of England and another to the Indian Prime Minister. And he wants to market the paintings in DVDs and books and share the revenues with Husain.

Recent newspaper reports have questioned whether the businessman, who self-confessedly had no interest in contemporary Indian art till recently, has the financial muscle to be able to pay up the full amount. Srivastava, pointing out that his group?s projected turnover for 2004-05 is about Rs 500 crore, reveals his plans for the deal. So far, he has paid Rs 26 crore to Husain (?By cheque,? he says) and got 25 paintings of the OPCE series in return.

He will sell this lot and, with the proceeds, buy the next instalment of 25 paintings due in December. ?The payments will then enter a self-sustaining cycle. Already people are approaching me to buy these paintings. But in any case, I will honour my commitment,? he says, showing off a fat cheque he has just received as profit for some shrewd investment in stocks.

As for the deal he wonders what the fuss is all about. ?A ship carries Rs 20-25 crore worth of iron ore. It takes about three months time before the payment cycle is complete. When three ships are out, we are talking about Rs 60-75 crore. So what is so great about a one-year deal of Rs 100 crore?? asks the businessman, also an MSc in chemistry from IIT, Delhi.

Srivastava, who among other things has also dabbled in wind energy and hotel construction, feels his initiative is a step towards the corporatisation of Indian art. At least, it has helped Swarup Group of Industries encounter fame. ?I was aware that my company will enjoy the rub-offs,? he admits.

Clearly, the son of a school principal who once played cricket with actor-friend Raj Babbar in the mohallas of Agra is enjoying his place in the spotlight. As a child, he would see his father draw the entire globe on an egg while teaching him geography. ?I was fascinated by what he did. But I was never able to do it myself,? says Srivastava.

For the time being, Guru Swarup Srivastava is happy changing the map of the Indian art world. Whether it changes forever or not remains buried in the bosom of time.