|

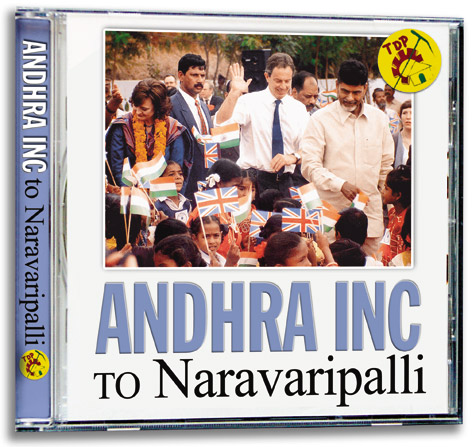

| BACKSPACE: British Prime Minister Tony Blair (centre), his wife Cherie (left), and Chandrababu Naidu (right) are greeted by school children during a visit to Vattam village in Andhra Pradesh in January 2002 (AFP) |

Narayana Naidu runs his index finger down the cemented floor of his house and draws an imaginary picture of a typewriter. “Does a computer look like this?” asks Narayana, a 20-something from Naravaripalli, home village of former Andhra Pradesh chief minister Chandrababu Naidu. Sure, he has heard of computers. But he has never seen one. Nor does he know much about its use. “Is it something that types letters quickly?” he wants to know. This is the last thing one might expect in a village, where the tech-savvy, laptop-toting ex-CEO of Andhra Inc. was born and raised. But it doesn’t surprise the villagers, the majority of whom belong to the Naidu clan. For, Naravaripalli — about 40 km from the temple town of Tirupati in Andhra Pradesh’s Chittoor district — doesn’t fall under Kuppam, Naidu’s Assembly constituency. To Naidu the politician, his constituency was clearly much more important than his native village, where his mother, a widow, still lives.

Prakash Naidu, a village youth, was amazed when he visited Kuppam, in the same Chittoor district, two years ago. “You wouldn’t believe it if I told you what uncle Naidu has done for his constituency,” he gushes. As he zoomed around Kuppam on a friend’s motorcycle, he counted 15 Net cafes in that town. “It’s possible that I didn’t see all of them,” he says. Unlike Narayana, who hasn’t had a chance to visit Kuppam yet, Prakash certainly knows what a computer looks like.

Little wonder that Kuppam stood by him when much of Andhra deserted Naidu’s Telugu Desam Party (TDP) early this week. Naidu won from Kuppam by 59,000 votes (his fourth consecutive victory from the constituency), but his party lost as many as 131 seats across the state in the worst drubbing it has received at the hands of the Congress in recent memory. But no tears were shed for Naidu (except, maybe, by his mother) in Naravaripalli, where residents are at best indifferent to what’s happened to their “Peddayana,” Telugu for elder brother. “He hardly did anything for us, so his victory or defeat makes no difference to us,” Venkataramana Galla, a villager, says.

Nearly 700 km from Hyderabad, the state capital that had earned the nickname Cyberabad during Naidu’s nine-year tenure as chief minister, Naravaripalli is a farming village near Andhra Pradesh’s border with Karnataka. It falls along a narrow, tar road that starts in Chandragiri (off the Bangalore highway) and ends in the hills edging the horizon.

This road is part of village lore. It was built in just three days after Naidu took over as finance minister in 1994 to enable him to visit his village without trouble. Locals stress that the road is one of the few things Naidu has done for the village in his 28-year-long political career. His most spectacular achievement, however, is a black granite monument that he built in memory of his late father, Kharjura Naidu.

A brick building set in a vineyard greets visitors at the entrance to the village. It is a public school built by Telugu actor Mohan Babu, former Telugu Desam Rajya Sabha member. (The area is not very far from Madanapalli where Krishnamurti Foundation’s well-known Rishi Valley School is located). Naidu and Mohan Babu, who had once been very close, fell out after Naidu grabbed the mantle from his father-in-law .T. Rama Rao in a palace coup in 1995.

At the centre of the village stands Chandrababu Naidu’s imposing bungalow, fronted with a well-tended lawn and a balcony. Naidu’s mother Ammanamma lives here, guarded round the clock by the Central Reserve Police Force jawans, a reminder of the Naxalite threat looming over the family since the former chief minister had a narrow escape in Tirupati last October. The area is thickly forested and police say that it is stalked by gun-toting extremists from the People’s War Group. Neither Chandrababu Naidu nor his younger brother Ramamurthy Naidu lives in the villages. They hardly ever come to the village and that too, for a few hours to attend family functions.

Compared to many villages in the region, Naravaripalli is prosperous. It has a 20-bed hospital, a veterinary hospital, two ration shops and a high school. It has electricity and telephones and it is connected to Tirupati by bus. But Naidu can hardly take any credit for this. Villagers say the hospitals and the school had been set up long before he became chief minister in the mid-Nineties.

The village has a population of 5000 people, most of whom are nara, an upper-caste community Naidu belongs to. The Naidu clan holds more than 100 acres of land in the village. Most villagers have land, which they use to grow paddy and vegetables. “Ours is a self-sufficient village, but that’s no thanks to Naidu,” says one of the elders, sitting in the village square.

Though located in a hilly and arid region, Naravaripalli happened to escape the great droughts of 2000 and 2001 that saw hundreds of farmers committing suicide elsewhere in the state. The village was also left untouched by the swarms of pests that fed on cotton — another scourge that drove farmers to suicide in districts like Nalgonda and Warangal around the same time. That was the time when tomato sold for 20 paise a kilo in some parts of the Chittoor district, according to R. Chenga Reddy, a Congress legislator from the region.

“The water level did go down, but there was no drought here. Nor did anybody committed suicide,” says Bhanumathi Nara, a schoolteacher in Naravaripalli. But then, with little irrigation available in the village, agriculture is still largely dependent on the monsoons. While Naidu worked hard to make Kuppam, his constituency, into a model for micro-irrigation to conserve water and boost agricultural incomes, villagers of Naravaripalli have largely been left to fend for themselves. It was in Kuppam that he launched his pet Janmabhoomi programme in the mid-Nineties, touting it as a model for participatory development. But when residents of his village cleaned the drains, dug borewells and built walls under the programme a few years later, there was no one to pay them. “Since we belonged to the chief minister’s village, we were too embarrassed to agitate for the money due to us,” says Venkataramana Naidu, a relation of the former chief minister.

Institutes of all kinds came up during Naidu’s tenure and Kuppam benefited from Naidu’s information technology (IT) initiatives, with the computer majors focussing on the town. Naravaripalli, by contrast, never heard the pings of e-governance in the last nine years. Forget about the virtual administration, even the administration on the ground hardly worked. “Officials come and go at will in our village. Sometimes, they won’t even open the offices unless prodded by the villagers,” a resident says, adding that the revenue officials had given the village a wide berth for nearly a decade.

Naravaripalli lost its importance when Naidu abandoned Chandragiri — the Assembly constituency that includes the village — for Kuppam, which elected him for the first time in 1989 as a TDP candidate. Today, it has an image problem. The Congress MLA from Chandragiri steers clear of the village since it is packed with Naidu’s relations. “It’s true that many of us are related to Naidu, but that’s no sin. Our MLAs should come to us to listen to our grievances,” Bhanumathi Nara, the schoolteacher, says.

Naravaripalli may be the birthplace of Naidu, but villagers insist that many of them do not support the TDP. Of its 1000 voters, at least 300 had voted for the Congress in 1999. Now that the Congress has returned to power in the state, many fear that Naravaripalli would be punished for being Naidu’s home turf. “We have had the worst of both worlds. Naidu did not bother about us as long as he was chief minister. The Congress may now do the same,” a local resident says.

The village has had its moments, though. For instance, soon after Naidu introduced high-tech farming in his constituency with the help of the Israeli government, the entire village was bussed to Kuppam, some 100 km away, to see the “marvel” for themselves. “We were kept in hotels and guest houses for a few days, free of cost. Naidu’s government paid for the entire trip,” Govindappa, a small farmer who made the trip, says. This was the most that villagers say they got from the man who made it big in Hyderabad. They don’t resent Kuppam, however. “It’s good that Kuppam has blossomed under his patronage. But we would have been happy if he had done something for his native village as well,” a villager says, with a tinge of sadness in his voice.

The villagers do not really mind the fact that Naidu’s much-vaunted IT revolution has passed Naravaripalli by. Given a choice, Narayana Naidu, the village youth, who has never seen a computer, says he wouldn’t have asked the former chief minister for a computer. “We need more jobs, an irrigation canal and a couple of more buses to Tirupati. These are the things we need most,” he says. “What would I have done with a computer anyway?”

Today, many would agree with Narayana. Andhra villagers, reeling from droughts, had clearly wanted Naidu to provide them with “what they needed most”. They simply deleted Chandrababu Naidu when they got computers instead.