Imagine the countless stories of women that never got told. So many that even now a story will crawl out of the margins of history and take us completely by surprise.

Some years ago, researcher Jennifer Howes came across a document in the British Library in London, UK. It was a list of hundreds of prisoners of Vellore Fort from 1823. Says Howes, “The prisoners all had women’s names, so I decided to explore who they were and why they were there.”

Her research and findings were the subject of an online talk organised by the Royal Asiatic Society in December 2021. It was titled “The Story Tellers of Mysore: Tipu Sultan’s female entourage and the 1806 Vellore Mutiny”.

The Vellore episode is not very well-known, though historians agree that it is the ideological precursor of the uprising of 1857. Fifty years before the greased cartridge became a flashpoint between sepoys and the East India Company, a section of the Vellore garrison rose in rebellion. Why? The commander in chief had issued some dos and don’ts — wear a new kind of turban; no caste markers on the face or earrings, no sporting beards.

In his paper “The Causes of The Vellore Mutiny”, K.K. Pillay writes that William Bentinck, who was the governor of Madras at the time of the rebellion, admitted to being aware that certain persons “spread alarm on the ground that these changes were preparatory to the conversion of the soldiers to Christianity”. Lt Col R. Huddlestone, who was in charge of the Arcot cantonment, believed the “disturbances” had been caused by the “Princes”. These “Princes” were the sons of Tipu Sultan who had moved to Vellore after the siege of Seringapatam and the death of their father in 1799.

Howes’s research can be read as one of the backstories of the backstory Bentinck knew of and Huddlestone suspected.

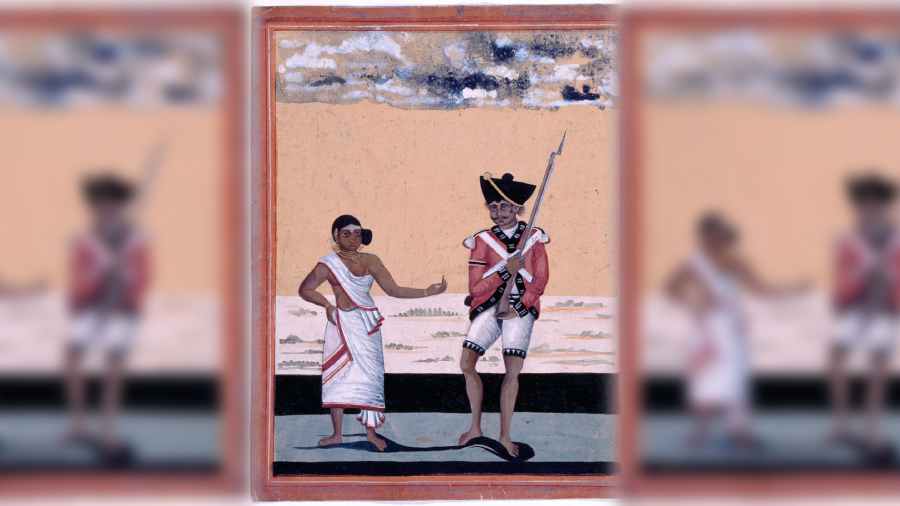

The fort at Seringapatam housed the women of Tipu’s inner court. There were hundreds of them organised in distinct hierarchical order, with wives of Tipu and his father Hyder Ali right on top. Next were the masarratis or performers. Below them were cooks, cleaners, messengers, dairy workers, seamstresses, nurses. Most of them were Mysorean Hindus, while others were from Delhi, Kashmir, Arcot, Hyderabad, Tanjore and some had been purchased as slaves from Constantinople and Georgia.

Hyder Ali’s chief of artillery, the Frenchman Maistre de la Tour, writes in his book In The History of Ayder Ali Khan, Nabob-Bahader that the performers were all women. He notes that their performances were all pieces of intrigue, either about women who get together to deceive a jealous husband or girls who conspire to deceive their mother.

Says Howes, “The masarratis could perform before men and women outside the palace too. If there was a big wedding or celebration, they would perform as representatives of Tipu’s female courtiers.” In another paper, “Roshani Begum, dancer turned rebel from Tipu Sultan’s court”, Howes writes that one such was the mother of Tipu’s eldest son Fateh Haidar.

So what’s all that got to do with the Vellore uprising? Turns out, after Tipu’s death and the re-installation of the Wodeyars as the rulers of Mysore, the company asked young orientalist Thomas Marriot to prepare a report on the 601 women of the inner court and reduce their numbers. Why such due diligence? The answer to that one is possibly quite another story.

But on the face of it, this is what happened. Marriot submitted a detailed report and sent away nearly half of them. The company made preparations to move the rest to Vellore Fort. But days before the big shift of 1802, the numbers swelled to 500-plus. This angered Thomas Dallas, the East India Company’s man at Vellore. He demanded that the newcomers be sent back, but the women raised such a commotion that he eventually gave in.

About 6,000 uprooted Mysoreans followed these women to Vellore. Howes says, “This meant the first-class masarrati women still had an audience.”

And still no seeming connection with the sepoys’ revolt?

At this point, the reader must join some dots.

Dot A. The rebellion happened on July 10, 1806. Dot B. February. Bentinck slashed the women’s allowances. Dot C. Between February and July, four of Tipu’s daughters got married. On every occasion there was dancing and singing inside the fort. The content written and narrated by women such as Roshani Begum, were about women deceiving their superiors.

More dots. May. Two havaldars refused to wear the new uniform. Threats of community and domestic ostracism. “Their families had said they would not live with them or prepare their rice,” says Howes. On July 10 a wedding was happening inside the fort. That night the sepoys rebelled. They killed close to 200 British soldiers, raised the flag of Mysore Kingdom, and declared Fateh Haidar, king.

By next morning it was all over. The Company had taken control of the fort. Soon after, Tipu’s sons were sent to Calcutta. And the women? They remained prisoners in Vellore Fort until they died.

Says Howes, “The reports I’ve found were by British men, so when the women of Tipu’s court are discussed, you know it is because they were making a lot of trouble. That is what has made this project so interesting for me. We are helping them have their #MeToo moment.”

Now, imagine all the other stories waiting to be told.