Book: My Pen Is The Wing Of A Bird: New Fiction By Afghan Women

Author: Afghan Women

Publisher: Quercus

Price: ₹599

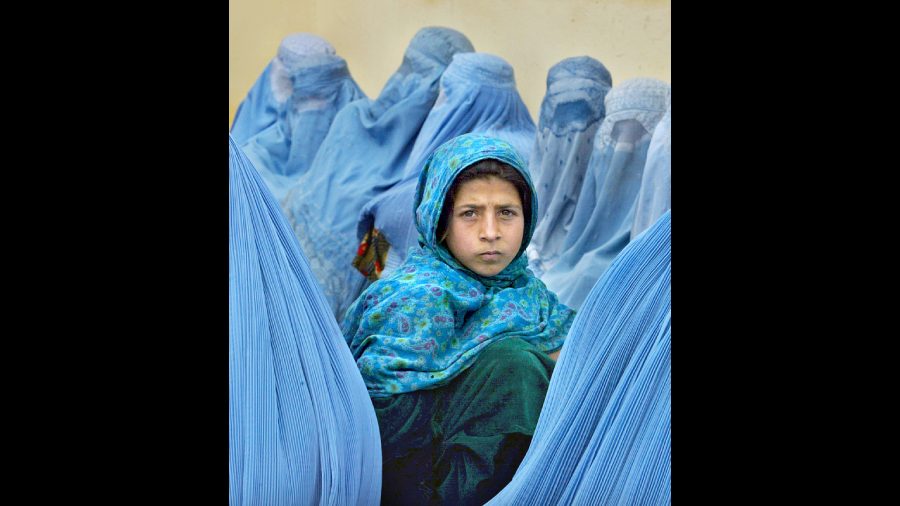

My Pen Is the Wing of a Bird is likely to be considered a historically significant piece of work in the near future: it is the first anthology of short fiction by Afghan women. Eighteen anonymous writers write about family and friendship, growing up, coming to terms with oneself, and living a life in a war-ridden country still fraught with pre-modern cultural traditions. The text has stories translated from the two main Afghan language groups, Pashto and Dari. The direct prose of the translations is a fitting choice for the accounts of a country rubbed raw with continuous violence. It is a powerful anthology that will forcibly expand the reader’s horizons.

These are the stories that go untold because they are considered too trivial or they do not spread well enough to merit dissemination in popular social media. But these are more than stories — these are insights into human lives: a courageous woman who saves her village, a writer of petitions who contemplates his life, a headmaster going to work, a teenager exploring her identity. There are stories of women with expected and unexpected twists. All the stories are different, but all of them present an informative as well as an enlightening slice of life from Afghanistan. Some aspects are culture-specific, like giving birth to a daughter in a society that desires sons, or living with the co-wives of one’s husband. While the former is an anxiety familiar to all of Asia, especially the Indian subcontinent, the latter may not be as easily imagined by everyone. Some aspects are situational, like trying to lead one’s daily life during a mortar attack. Another aspect combines universal and specific conditions, like pets and imaginary situations providing temporary relief from the volatile circumstances caused by internecine wars.

Human beings often endure hardships, individually and collectively. To suffer through decades of continuous war, abuse, death, and the trauma and grief they bring, not to mention poverty, hunger and the utter lack of certainty in life, speaks of an unusual endurance. There is a determination to fight for education, equality, and humanity. The question is: can the readers sympathise, let alone identify, with the plight of Afghan women? One remembers Syed Mujtaba Ali’s Deshe Bideshe, where the reader encounters Idanjaan, the singer in absentia, and her remarkable voice not being loud enough to reach outside the Afghan village she had presumably disappeared into. The daily lives of Afghan women are like our own only on a basic yet abstract level — a life structured around the family, especially the men, the repetitive cadence of housework, and school and work where possible. The differences are unimaginably appalling and, yet, they constitute real life for so many women. Any reader who has the luxury of being appalled is invariably privileged, whether she/ he realizes it or not.

After August 2021, Afghanistan has remained in the news primarily for its shock value, but no political power seems to want to intervene in its ‘internal affairs’. As a result of internal influences and the lack of external intervention, the women of Afghanistan are slowly and surely vanishing from regular, normal life as most countries see it. One is, yet again, reminded of Mujtaba Ali’s account of the changes forced upon the women by every regime, in terms of dress, conduct and education. It is startling how the plight of the common people, especially women, has not changed much in Afghanistan since 1948.

A major part of the text’s significance lies in the courage of the authors. As one reads, one is reminded of Nadia Murad and her horrific, aching memoir, The Last Girl. Some of the authors have fled the country, others have been unable to do so. All must keep their identities secret for some time and that in itself is heartbreaking. We who clamour that their voices must be heard cannot guarantee their safety should they be known. In the Afterword by Lucy Hannah, which discusses the circumstances of the compilation of this book, it is clear that these stories cannot be published in Afghanistan now. Bengali readers will find an echo of Mujtaba Ali again in Hannah’s opinion that Afghanistan has never been heard or understood.