Book: Resisting Dispossession: The Odisha Story

Authors: Ranjana Padhi and Nigamananda Sadangi

Publisher: Aakar

Price: Rs 695

What is the relationship between democracy and development? For generations of Indians, both virtues were hard-won rewards of the freedom movement and were guaranteed simultaneously after 1947, through the Constitution, along with universal adult franchise and five year plans. For the more historically minded individual, the question is less easy to answer. Industrialization occurred in European countries in the 18th and 19th centuries in the absence of popular democracy. Peasants were forcibly uprooted to make way for factories and capitalist farms, indigenous communities were decimated, and colonies like India were politically subjugated for markets and resources. Ranjana Padhi and Nigamananda Sadangi’s Resisting Dispossession: The Odisha Story forces us to confront a similar reality not on the pages of European history but in the forests, rivers and villages of contemporary India.

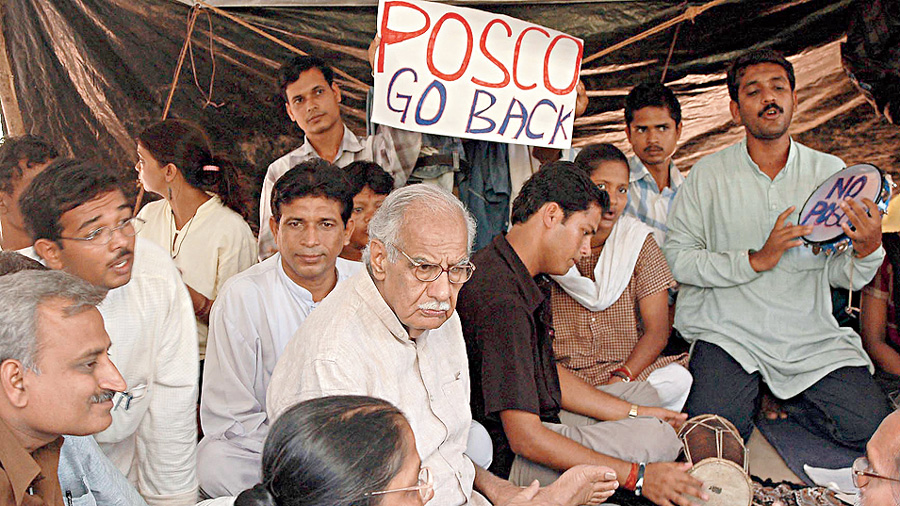

The book is an account of peasant movements against industrial and development projects in Odisha, from the protests against the Hirakud dam in the 1940s to the struggle against the South Korean steel company, POSCO, in the 21st century. Each chapter takes up a site and a project and there are 10 chapters about movements against dams, bauxite mining, and land acquisition for steel production, alumina refineries and a missile testing range. What is unique and powerful is that the authors have interviewed ordinary villagers who participated in these struggles and were witnesses to the violent disruptions of everyday life and agrarian livelihoods that marked the entry of a project. The interviews are presented almost verbatim; there are first-person accounts by schoolteachers, students, government employees, shop owners, priests, fisherfolk, landless labourers and, of course, farmers. Women speak directly to the authors, from a mother who lost her son to police firing in Kalinganagar and was arrested for sedition many years later to elderly women who reminisce how they had inspired protests against the Baliapal missile testing range by blowing the conch.

Resisting Dispossession: The Odisha Story by Ranjana Padhi and Nigamananda Sadangi, Aakar, Rs 695 Amazon

What emerge are the suffering of the budianchalia, the displaced people, the unfulfilled promises that mark the lives of families in the rehabilitation colonies, and the pain of those who were attacked because they did not want to give up their hills and rivers. While the government and the media often focus only on violent acts of resistance, Resisting Dispossession shows that villagers also sang songs, performed plays, danced and found creative ways to survive while barricading themselves for months against hostile district administrations. Despite the presence of panchayats, political parties, elections and elected governments, the State consistently violated its own laws. Rather than dialogue or negotiation, it relied on cunning, force and brutality and curbed people’s liberties and fundamental freedoms every time it needed their habitats, their bheetamati. As the authors write in the epilogue, there are no happy endings in this story. Not all peasant movements were successful in stopping the projects. For communities that were successful, it has been a pyrrhic victory — they have to contend with court cases, counterinsurgency operations, social rifts caused by movement politics, economic losses and an uncertain future.

What then of democracy and development? The authors demonstrate that laws, democratic norms and political institutions are an obstacle or a fig leaf when it comes to industrialization that requires the separation of communities from their land and livelihoods. Until we can reimagine development in ways that revolve around the well-being of communities and ecosystems, people who depend on the soil, the trees and the fish will continue to resist dispossession and development.