Book: Languages of Truth: Essays 2003-2020

Author: Salman Rushdie

Publisher: Penguin

Price: Rs 799

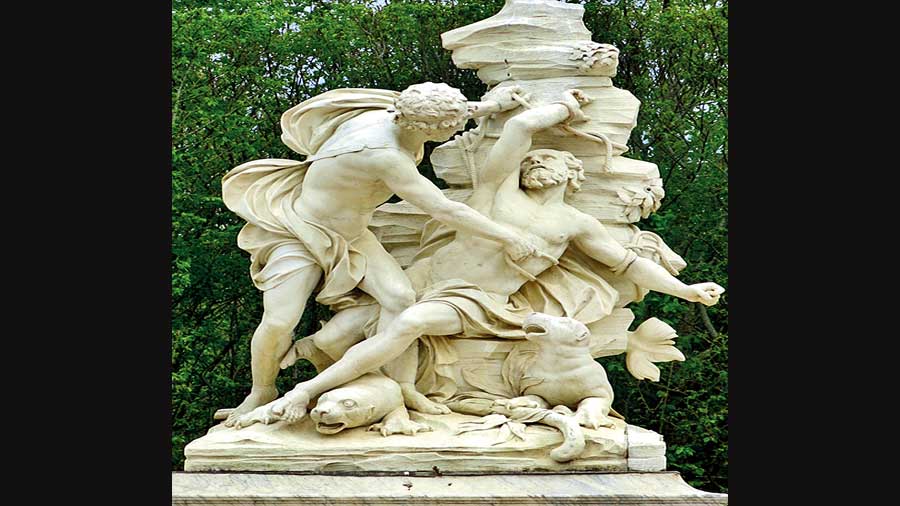

In Homer’s Odyssey, Menelaus recounts how he captured the slippery sea-god, Proteus, and held him fast through successive metamorphoses, forcing him to return at last to his own shape and speak the truth. James Joyce names the third section of his modernist epic, Ulysses, after Proteus, and presents us with Stephen Dedalus on Sandymount Strand, in search of the truth of the world and his own being, wrestling with the endlessly mutable forms of language. “Proteus”, the second essay in Languages of Truth, a collection of Salman Rushdie’s shorter non-fiction from the past two decades, cites the Proteus myth from Virgil’s Georgics and Ovid’s Metamorphoses rather than Homer or Joyce, but the relation between shape-changing and truth, language and reality, remains at the heart of Rushdie’s writing. Reality, like language, is protean, Rushdie tells us, and this does not mean that it is not true, but rather that you must hold fast to its mutable forms in order to learn its truth — or truths.

In what is now a long literary career, although to someone like myself it seems just the other day that I was reviewing Midnight’s Children, Rushdie has held fast to the protean nature of reality. “This is what I’m wrestling with,” he says, “this great shapeless mutating blob that can’t even agree with itself about what it actually is, this is what I’m trying to give shape to.” In a review of Francesco Clemente’s self-portraits, written in 2005 and placed late in this volume, he returns to the theme of metamorphosis, “the art of the protean”, which, Rushdie feels, embodies the truth of the mutable self, the changing world and the chameleon artist. Representation, too, must surrender to chance, oddness, and paradox, for the line between fiction and reality is never sharply defined, but blurred and smudged. This protean world requires every shift of language at Rushdie’s command, and the geniuses from whom he draws inspiration are Cervantes and Shakespeare. A brass door-knocker shaped like Shakespeare’s head, he tells us, admits him to his study.

Languages of Truth: Essays 2003-2020 By Salman Rushdie, Penguin, Rs 799 Amazon

Many of the essays in this volume, including the ones adapted from talks given at Emory University, the inaugural Eudora Welty lecture delivered in 2016, and some of the material composed for PEN, reiterate Rushdie’s view that the world is a strange, magical, fantastic place, filled with an abundance of stories, wonder-tales like those related by Scheherazade to her genocidal husband, Shahryar, in the Arabian Nights to stave off her impending execution. This might suggest that what lies beyond fiction, beyond the marvellous constructions of language, is death, the writer’s death or the death of the imagination. But this is not really so, for as Rushdie says in his essay on Proteus, silence might also be a writer’s choice, as it was, mysteriously, for Shakespeare, who retired to Stratford after making his fortune and ceased to write. Between expressive intent and self-willed silence lies the world of literature and art, about which Rushdie writes eloquently in these essays.

Part of the charm of this book for Rushdie’s admirers is its frequent recourse to autobiographical vignettes, directly in “Another’s Writer’s Beginnings”, “The Liberty Instinct”, “Autobiography and the Novel”, “The Unbeliever’s Christmas”, and “Pandemic” but also, by way of revealing anecdote or parallel, in essays on writers or artists he admires, like Philip Roth, Kurt Vonnegut, Gabriel García Márquez, Samuel Beckett, Christopher Hitchens, Amrita Sher-Gil and Bhupen Khakhar, or, rather unexpectedly, in “Notes on Sloth”. This is a reminder that one does not read literary reviews by major writers simply for information about literature or art, but to know more about the author’s own, unique vantage point. That such a vantage point may also yield insights into the work of other writers is a bonus. Thus there is much to learn from Rushdie writing on Roth, two immensely creative and important writers who did not win the Nobel Prize for Literature. Roth, who died in 2018, the year the Nobel in literature was not awarded because of the sex abuse scandal, will never win it now. Rushdie’s chances worsen every year he does not get it. Yet, both would make it to any list of the greatest novelists of the twentieth century, Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children having a claim to being the most influential book, worldwide, in the past fifty years.

But one great merit of this collection is that it does not leave you yearning solemnly for Rushdie’s missing Nobel Prize address. Ranging from the slight to the serious, the idiosyncratic to the polemical, often in Rushdie’s characteristic vein of self-deprecating irony, the pieces are a pleasure to read for their variety, sharpness, and literary brio. One of the best essays here is on “Adaptation”, a frank and entertaining set of observations written on Oscars Night 2009, mainly on films adapted from books (including scathing comments on Slumdog Millionaire). Another, “The Half-Woman God”, is a personally-researched study of the hijras of Mumbai. A third, “The Composite Artist”, is about the making of the Hamzanama, the extraordinary sequence of fourteen hundred paintings (of which fewer than two hundred survive) commissioned by the Mughal emperor, Akbar, soon after his accession and completed only fifteen years later. In the universe of the Hamzanama, says Rushdie, opposites coexist: “violence and beauty, realism and phantasmagoria, heroism and villainy”. This is the universe that Rushdie has sought to capture in his fiction. Languages of Truth illuminates some of the choices, influences and beliefs that have driven this lifelong venture.