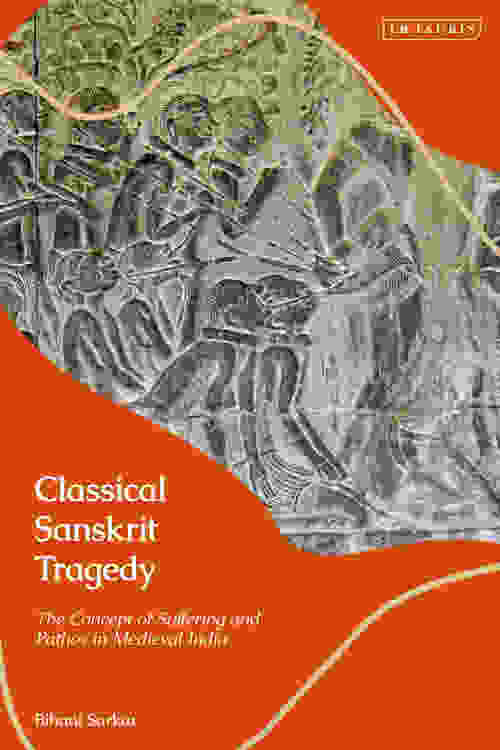

Book: Classical Sanskrit Tragedy: The Concept of Suffering and Pathos in Medieval India

Author: Bihani Sarkar

Publisher: I.B. Tauris

Price: £85

Bihani Sarkar’s compelling Classical Sanskrit Tragedy: The Concept of Suffering and Pathos in Medieval India raises an old question in an entirely new way: is there tragedy in classical Sanskrit literature? The book explores the concept of tragedy in two ways. First, it places Sanskrit drama in conversation with European notions of tragedy as a genre. Sarkar’s second project is sparklingly original. She offers a revisionist reading of Kalidasa, laying out a phenomenology of grief in these texts. This meticulous cultural history provides insight into how suffering and pain were conceptualized as experiential categories in early India.

The Introduction establishes the main problematic of the book. Sarkar first provides definitions of ‘tragedy’ and the expectations that come along with it in the Western canon. She explores both old and recent Indological scholarship, which have argued that classical Indian kavya is not tragedy. Such explanations focus on the fact that kavyas very rarely end with death, and they have sometimes overlooked the complex individual personalities of these dramatic characters. Sarkar pushes back against such readings and posits a rereading of kavya that focuses on interiority. By discussing rasa, especially the painful part of srngararasa, vipralambha, Sarkar argues that there is an ambiguous nature of the tragic in classical Indian tradition. Hope and despair are but two sides of the same coin, and the interplay of the two arises out of an embedded crisis found in the middle acts of Kalidasa’s dramas. This is not quite resolved with the reconciliatory ending.

The crisis is the avamarsa or vimarsa, the pause or the period of trial for the play’s protagonists in which they face obstacles, conflict, death, and disaster. Sarkar introduces us to the theory of narrative development in Bharata’s Natyasastra and glosses several commentaries, focusing on Abhinavagupta, to examine the role of the pause within this aesthetic tradition. In Sarkar’s reading, this pause was interpreted in two divergent ways. Some theorists designated this as avamarsa, an obstacle to the larger narrative arc of the drama driven by phalaprapti (attaining the goal/fruit). Other theorists found vimarsa to be the protracted period of deliberation and introspection by the protagonist ridden with doubt. Thus, the ‘tragic middle’ marked a disjunction in the path to a happy ending, being both a formal element in the play and, more importantly, “a form of inner experience of rupture”.

Classical Sanskrit Tragedy: The Concept of Suffering and Pathos in Medieval India by Bihani Sarkar, I.B. Tauris, £85 Amazon

The four body chapters display close philological readings that map and explain iterations of elegiac consciousness in Kalidasa’s oeuvre. Sarkar begins this discussion by relating these prototypes of grief to the Ramayana (an argument made by Robert Goldman, but she extends it) and to Buddhist literature such as Asvaghosa’s Saundarananda. She locates formulations of the lament that are similar to Kalidasa’s vilapa: broken promises, curses, remembering and reviving love through mnemonic symbols, and the gendered suffering of women in a world determined not by love but by dharma. Further, in Kalidasa, the vimarsa becomes a mode of asking questions about the causal powers behind grief and suffering. The second chapter discusses the genealogical narratives of the mahakavyas, Raghuvamsa and Kumarasambhava. She argues that these long poems do not create a feeling of triumphalist success in the continuity of the family line, offering instead a period of extended reflection in which the larger ideas of agency and causality are explored. Who is responsible for grief? Can one get over it or does it change one irrevocably? Here, Sarkar introduces the idea of grief as a state of being estranged from oneself, the state of alteritas or anyatha. The third chapter provides a close reading of Sakuntala’s trial, explaining how Dusyanta’s choices and actions ultimately exercise a profound impact on his own consciousness. Instead of seeing the curse and the amnesia as elements that drive the plot in a formalist vein, Sarkar delves into the philosophical implications of perception, memory, and recognition. The final chapter examines tropes of poetic substitution, such as tortured lovers, driven to madness by separation, entreating non-human messengers to carry messages to their beloved. Sarkar argues that the Meghaduta is not an exercise in demonstrating love’s irrationality but a lament. Meghaduta’s yaksa stands as a solitary figure whose path to healing is through exercising the imagination.

Classical Sanskrit Tragedy will be of great interest to both scholars and general readers. It is an erudite book with profound insights into the history of emotions in classical India. By drawing upon a large body of texts across kavya, nyaya, and the Buddhist canon, Sarkar explores how suffering has been cognized and expressed across these genres and traditions. Although not explicitly articulated as such by Sarkar, a startling revelation of the book is the gendered experience of grief. The book is a beautiful exploration of how pain leads to the breakdown of gender roles; male despair and fragility; and the shared features of female bereavement and anguish across secular and religious texts.