Book: The Great Hindu Civilisation: Achievement, Neglect, Bias and the Way Forward

Author: Pavan K. Varma

Publisher: Westland

Price: Rs 799

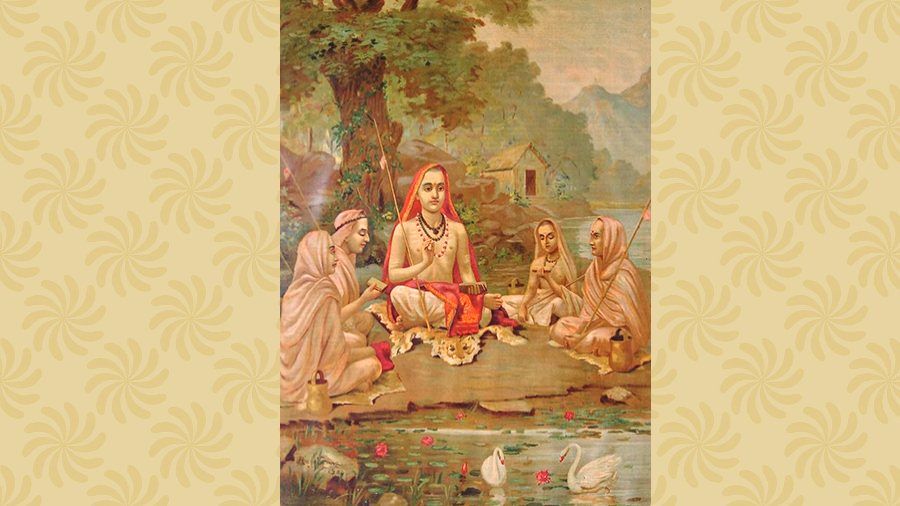

Pavan K. Varma wears many hats. For anyone who wears multiple hats, there is the inevitable danger of identities associated with one hat rubbing off on other hats. Even if the individual concerned sees no contradiction between these multiple hats, given our penchant for stereotyping and straitjacketing, the external world doesn’t quite perceive it that way. I am inclined to think that this book is part of a broader canvas, an attempt by Varma to seek out his roots. What does it mean to be Indian? What is the legacy of our samskrita, samkriti and samskara? I am deliberately using these respective terms for the language, culture and sacraments because they have a common etymological root and possess a nuance of cleansing and polishing. Varma has had (the verb should probably be in the present continuous) an interest in India’s culture, stimulated perhaps by his stint with the Indian Council for Cultural Relations. Hence, Ghalib and Delhi’s havelis. Anyone familiar with this prolific author’s output will recognize these strands as those that have figured in his earlier works, including Kama Sutra. To that earlier list, add ‘Adi Shankaracharya’ and ‘Krishna’ and ‘Ramcharitmanas’, the former representing ‘jnana’ and ‘Vedanta’, the latter ‘bhakti’. Anyone who individually delves into this glorious legacy and rediscovers one’s roots and is simultaneously familiar with the dismissive attitude of Western writers and those influenced by the West will be pained. It was no different in the 19th century.

In passing, despite the negative connotations that have come to be associated with the term, ‘Hindutva’, I prefer the usage of ‘Hindutva’ to ‘Hinduism’. The root, tva, has the nuance of truth, the essence. The suffix, ‘ism’, carries the nuance of dogma. In his search for his roots in Hindutva (he naturally uses the word, Hinduism), the author could have done a book on what it means to be Hindu, as others have done. Given the nature of Hinduism, that would have been a take on Hinduism as opposed to ‘the’ take on Hinduism. The indefinite article, rather than the definite article, is indicated. Every book has an objective, an intended readership in mind. Varma’s objective is set out in the Preface. “From my point of view, the fact that a great Hindu civilisation existed, and continues to exist, is not in doubt… It is important to know more about this civilisation, most of all for Hindus themselves… In this book, I have sought to rebut arguments that question the existence of Hindu civilisation, and deal also with the notion that the narration of history should expediently exclude Hindu religion and its civilisational consequences.” This is a rich and comprehensive book, with a broad canvas. The six chapters are titled, “Hindu Civilisation: Myth or Reality”, “The Audacity of Thought”, “The Realm of Ideas”, “The Islamic Conquest”, “British Rule and its Aftermath” and “The Challenge of the Modern Republic”.

To make the criticism a bit more specific, Varma could have written two different books, though the subjects do intersect. (a) This is my take on Hinduism and this is what Hinduism means today (to me). (b) Let me, argument by argument, rebut the standard criticisms. The latter is standard fare in nyaya darshana, where one sets out the opponent’s point of view (purva paksha) and counters it (uttara paksha). One celebrated instance of (b) is the Adi Shankaracharya versus Mandana Misra debate and we know from the author’s other work that he is fascinated with this episode. Given Varma’s extensive reading and understanding, I would have preferred a book that did (a). But given the objective he set out for himself, this book is (b), though understandably, there are shades of (a). Hence, a large number of words are devoted to countering the views of Amartya Sen, Romila Thapar, Jawaharlal Nehru, Wendy Doniger, Sunil Khilnani, Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Sheldon Pollock and Irfan Habib. “Sen’s concerted attempt to puncture the claim of Hindu civilisation sometimes assumes laughable proportions.” The first chapter, which sets the tone for the entire book, is replete with such instances. Every author is entitled to his own canvas. I felt Varma would have done more justice to himself and to Hinduism and written a better book if he had drastically pruned the first chapter and started with the second chapter, not pegging the volume to the negative strand of reacting, but presenting what Hinduism is and what it stands for. This concise description in the second chapter is primarily based on the six darshanas (schools of philosophy for want of a better expression), interspersed with Itihasa and the Puranas, but heavily overlaid with Vedanta. The third chapter builds on this and brings in elements of natyashastra, shulba sutras, vastushastra, ayurveda and arthashastra.

The last three chapters are on how historical developments have affected perceptions of Hinduism. I do hope Varma will write that (a) book.