Book: Forgotten Refugees: Two Iraqi Brothers In India

Author: Nandita Haksar

Publisher: Speaking Tiger

Price: Rs. 399

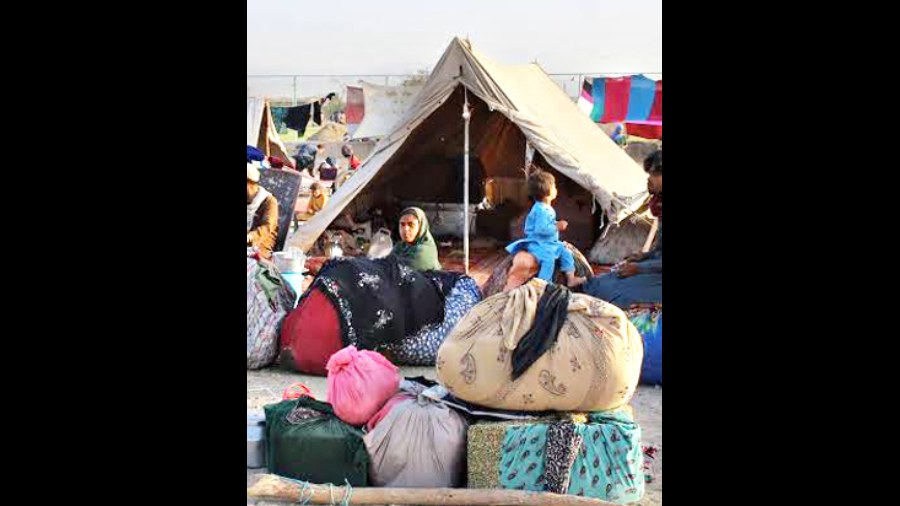

Nandita Haksar’s latest book is a moving reminder of why India needs a refugee protection law. The absence of one has led to a situation wherein some of the most vulnerable and marginalised human beings in the world have been cast aside as “illegal”. “Refugees are people, not statistics,” writes Haksar, clarifying her humanitarian position on the issue before supplying us with details about her protagonists, Babil and Akkad, the two Iraqi brothers that she ran into outside the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in Delhi in November 2021. They were camping at the gate along with other refugees from Africa and Afghanistan — all of them demanding their right to resettlement.

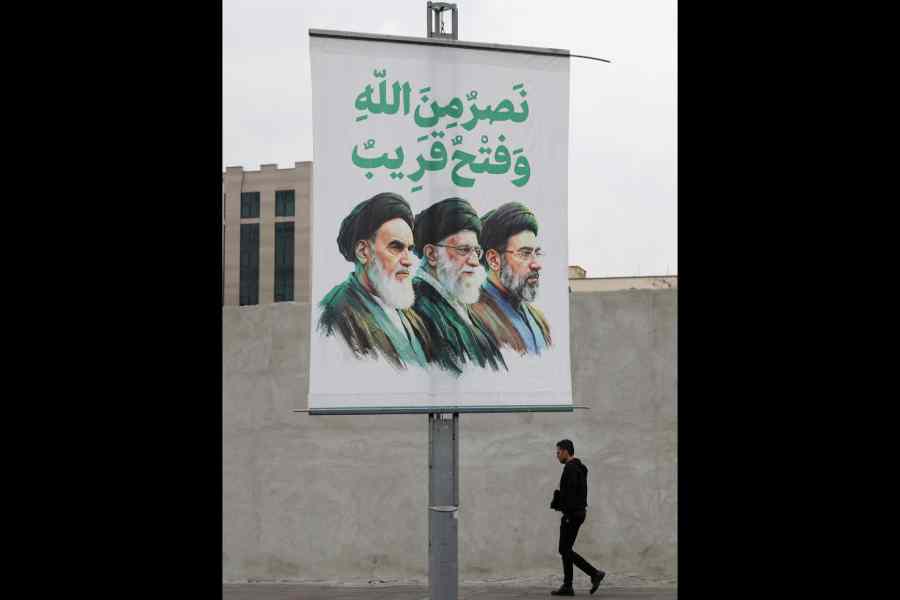

Babil, referring to Babylon, and Akkad, referring to the Akkadian empire, are not the names the brothers go by in real life. These have been assigned to protect their identities. They want to ensure that the contents of this book will not have adverse consequences for their family in Iraq. Haksar writes, “Calling themselves Babil and Akkad was a way of asserting their claim over their rich heritage — from ancient, pre-Islamic times to modern Iraq: a heritage which was subjected to intentional acts of violence and destruction by Daesh in Iraq and Syria.”

Babil was born in January 1988, seven months before the Iraq-Iran war ended in a stalemate. Akkad was born in April 1991, four months after the Gulf War started. They grew up witnessing violence at close quarters. They are in their thirties now in a country that they do not belong to and feel increasingly unsafe in. The few happy memories from their childhood are fading. They long for “a life without fear” and a place to call home.

How did they land up in Hyderabad? Why did they move to Delhi? What kind of informal labour markets did they participate in to meet their basic sustenance needs? Where have they been living throughout their time in India, without proper legal documents? When did they realize that they cannot trust even fellow Iraqis? Read the book to learn about the suffering that they have had to go through and how little the UNHCR has done to end their agony, especially during the Covid-19 pandemic when food and employment have been scarce.

Thankfully, Haksar resists the temptation to bring in her expert lens every now and then. She comments briefly on the historical connections between India and Iraq, offers some useful context that a non-specialist in refugee rights would require, and then stays in the background. She allows the reader to listen to Babil and Akkad. She becomes their scribe.

This stylistic choice is also a political one. She points out the need to move away from “patronizing narratives rooted in the politics of pity” so that we can hear what refugees want to tell us about the racism and the discrimination they face in countries where they seek refuge.

While their account is painful, it is not always serious. Dark humour helps them survive in a world that is growing increasingly suspicious of and hostile to “outsiders”, forgetting that the story of the human species is a story of migration, cultural exchange, and hospitality.