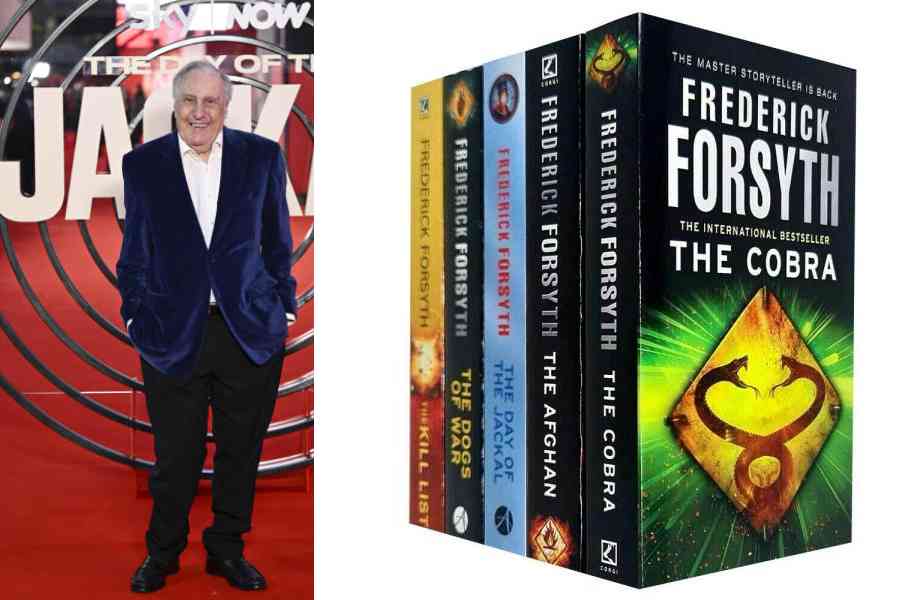

Some years ago, when he was at the peak of his career, I interviewed British novelist Frederick Forsyth, who passed away at the age of 86 on June 9 with more than 75 million copies of his suspense thrillers sold worldwide, and best known for his thrillers The Day of the Jackal, The Dogs of War and The Odessa File.

Long nicotine-stained fingers reach silently for the packet of Rothmans lying on the table at the Mandarin Oriental Hotel in Bangkok. We are seated on the verandah overlooking the brown Chao Phraya River. I am at breakfast with this — and the last — century’s most controversial thriller writer. His favourite companions — two eggs, sunny side up, bacon and two hash browns and toast with a generous spread of honey — are in attendance. His opening remarks to me were signature Forsyth style: “A writer has only himself. The weirdest job in the world and the loneliest one is being a writer. An actor has a cast, a pilot has a crew, and a doctor has a team. It’s no wonder that writers spend 50 per cent of their time in their heads, staring into walls or in space.”

The Day of the Jackal, his second book published in 1971, jump-started his career as a writer. His first book, The Biafra Story, about Africa, did not do much for him. He said: “To write The Day of the Jackal, I consulted a professional assassin, a passport forger, and an underground armourer,” referring to a maker or supplier of weapons. His 12 years as a foreign correspondent, mainly in Paris, helped him a great deal to get all the factual details correct. For Forsyth, it was a strong training in journalism that included researching and meticulously checking facts that made him into a wonderfully polished detective writer.

What prompted him to write The Day of the Jackal? “Well, it wasn’t an abused childhood,” he said with a wink. “And I am not driven to write either. Fame and glory do nothing for me. For me, it is simply a means to make a living.” And what a life Forsyth had led. For someone who began and ended his education at England’s prestigious Tonbridge School, but left at 17 to take a commission in the Royal Air Force, quite the youngest pilot on the runway for some years, he had not done badly at all. By the time he was 60, he had a dozen books under his belt that were circling a pretty fit gut. Still obsessed with The Day of the Jackal, he said to me with a big grin: “I completed it in just 35 days flat.”

The story, about an attempt to assassinate French President Charles de Gaulle in the summer of 1963 was so convincing that the French newspapers actually sent out reporters to check out some details. Forsyth’s The Day of the Jackal was immortalised on celluloid twice: the first was “the brilliant 1973 version” by the writer’s own admission, starring Edward Fox and Michael Lonsdale; and the second was the 1997 film Jackal starring Bruce Willis, Richard Gere, and Sidney Poitier.

“I became a novelist by accident, purely, never intended to write, never really wanted to,” said the author in characteristic staccato sentences, catapulting his words like little bullets. “After a dozen years in journalism as a correspondent in Africa and Europe for Reuters, BBC, and a host of other news agencies, I found myself without a job. So, I thought I’d try and earn a living by writing a book.”

It had been quite a life — meeting mercenaries, being accused of allegedly financing an attempted coup in Equatorial Guinea, and hobnobbing with arms dealers. Forsyth has had as much drama in real life as the antiheroes he has fashioned. And he seemed to be as tough as the Jackal — despite having lost more than one million British pounds to a money manager in 1987, who squirrelled away Forsyth’s life savings, the thriller king bounced right back. “I began all over again from zero in 1991,” he told me. “And made it all back again and more. Now I never put all my eggs in one basket.”

Over the next five decades, the bestsellers continued, with plots including nuclear weapons, the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, the cocaine trade and Islamic terrorism. One time, he was being hunted down while researching a criminal conglomerate and was given 80 seconds to get out of the city. He just managed to get his passport and documents and get on a running train by the skin of his teeth!

An outspoken critic of Tony Blair, Forsyth was a staunch supporter of Brexit, becoming a patron of Brexit campaign group Better Off Out, and wrote of his scepticism of climate change in his Daily Express column. Forsyth was never romantic about the art of fiction, repeatedly announcing his retirement and complaining that he had to force himself to write. “I am slightly mercenary,” he said. “I write for money.” But Forsyth kept complete faith in his typewriter and wrote more than 25 books, which sold over 75 million copies in more than six languages.

How did the creative work for him? “I tend to prepare very slowly, and then I write very fast. Twelve pages a day, that’s it. About 1,200 words seven days a week. I prepared Jackal over six years, from 1963 to 1969, and wrote it straight from the top of my head in 35 days! I follow the same routine. Rise very early, maybe 5am, and then write until 1 or 2 pm when I’ve done my 12 pages. There are days when it flows and other days when there’s technical stuff, it’s tough making those 12 pages.” The plots of some of his best thrillers, he said, “gelled in the mind during hours of staring into space”.

Forsyth would rather fish in the streams and spend his time in his leafy country estate in Hertfordshire, where he lived with his second wife, Sandy and twin sons Frederick and Shane. Mesmerised by the ocean, he wanted to dive into the sea off Phuket. A serious angler, he enjoyed the calm of going fishing in the Caribbean, Mauritius, and the Andaman Sea. “You don’t know how lucky you are to live in this beautiful, luxurious city of kings,” he said as he extended his right arm and a charming smile that made him seem like a naughty schoolboy. I understood why the Hollywood stars like Faye Dunaway had fallen for the thriller king.

Forsyth’s legendary legacy is The Biafra Story (1969), The Day of the Jackal (1971), The Odessa File (1972), The Dogs of War (1974), The Shepherd (1975), The Devil’s Alternative (1979), Forsyth’s Three (1981), Visitor’s Book: Short Stories of their New Homeland (1982), Emeka (1982), and many others.

Julie Banerjee Mehta is the author of Dance of Life and co-author of the bestselling biography Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught World Literature and Postcolonial Literature for many years. She currently lives in Calcutta and teaches Masters English at Loreto College, is a literary columnist for t2 and conceptualises and curates the Rising Asia Literary Circle