You who wronged a simple man/ Bursting into laughter at the crime,/... Do not feel safe. The poet remembers./... The words are written down, the deed, the date.” — Czeslaw Milosz

For William Wordsworth, poetry may well have been the recollection of the poet’s feelings in a moment of tranquillity. But reality is not all rainbows and unicorns — or daffodils, for that matter — for everyone. In a world ravaged by conflict, the task of the poet is often to keep alive memories, not of bliss, but of the sufferings of people subdued by the dominant discourse of the day, and relegated to the margins as a forgotten chapter in history. From Milosz in exile from his beloved Poland and Anna Akhmatova (“Poem Without a Hero”) for her fallen comrades at Leningrad to Lalita Pandit Hogan (Anantnag) who took up the pen for Kashmiri expatriates and Puneet Sharma (Tum Kaun Ho Bey?) who does the same for citizens harassed by ultra-nationalists, men and women of verse have, time and again, taken up the mantle of being the spokesperson for and the chronicler of the oppressed.

What the poet reifies are struggles and resistance that transcend time and space. Perhaps that is why a 1937 poem against a racist murder in the American South, Strange Fruit, could have been appropriated — over 70 years later — in a poem about the suicides of Dalit students in India. Again, “Write it down! I’m an Arab”, written by a Palestinian poet in 1964, is echoed in the words penned by a marginalized Assamese Muslim five decades later in “Write down/ I am a Miyan”, or inspires a citizen threatened with disenfranchisement to declare, “Write me down/ I am an Indian”.

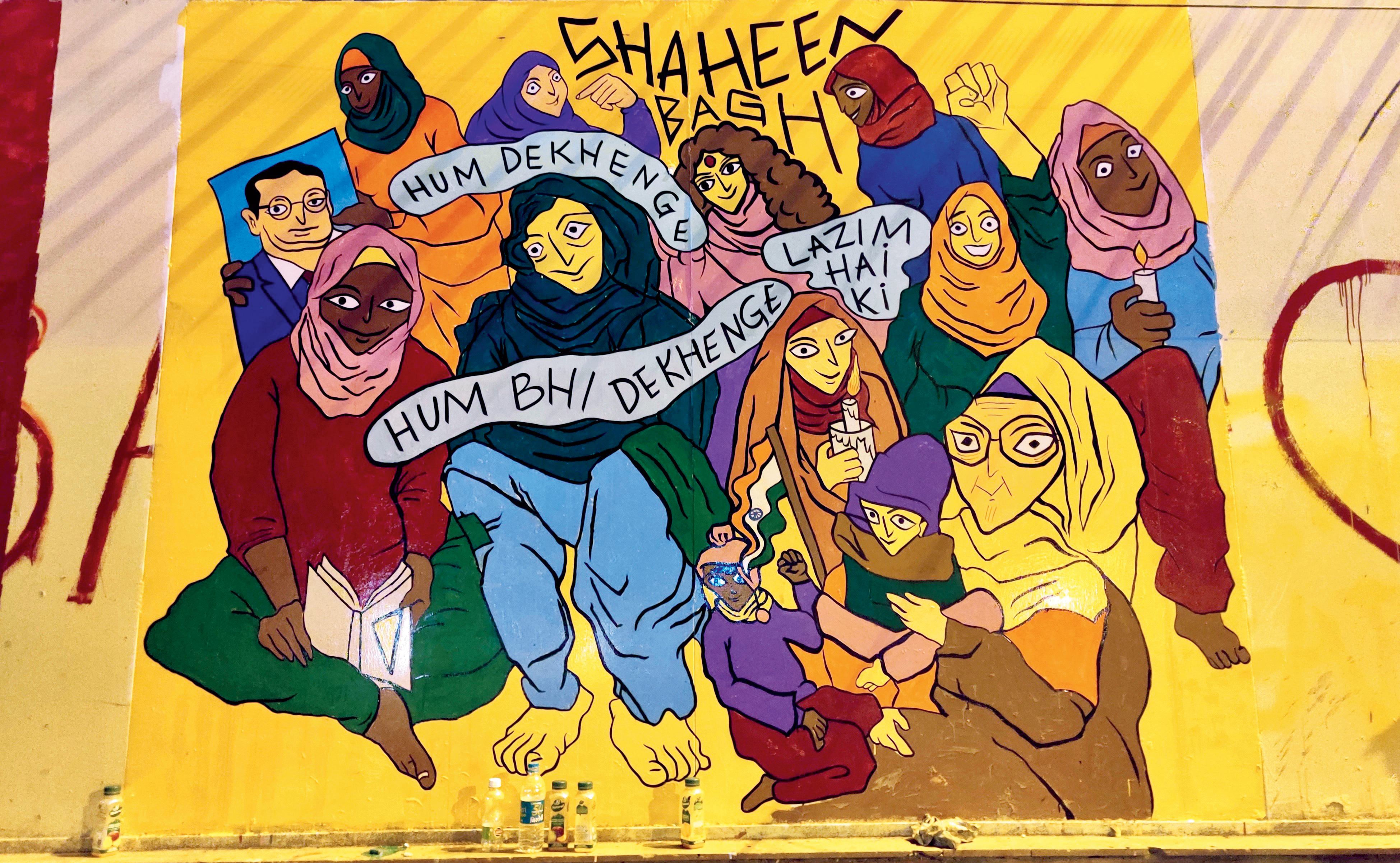

It is poetry, more than cold facts, that connects people in restive times, galvanizing movements against systemic injustice, leading to the fruition of slogans and songs. Recently, as hundreds of people in India raised their voices in protest against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, poetry spilled out from the page onto the streets. Public squares became symposiums, and poetry became performance: protesters recited verses by established poets — Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s Hum Dekhenge rang out in different corners of the country — as well as those by new voices — Aamir Aziz’s Sab Yaad Rakha Jayega was read out in translation by the musician, Roger Waters, in London.

Poetry truly fulfils its purpose during such decisive moments in history. Descending from the lofty pedestal to which it is banished by idle minds, it offers more than succour to the distressed. For even though public memory is weak, and the collective conscience fickle — poets and their poetry flicker as the beacon of hope.