Book name: A Patchwork Quilt: A Collage of My Creative Life

Author name: By Sai Paranjpye,

Publisher: HarperCollins

Price: Rs 599

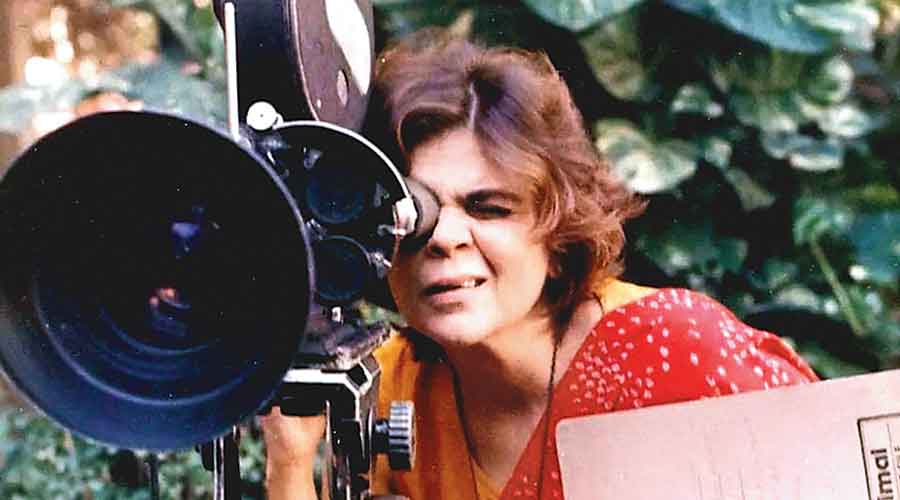

Sparsh, Chashme Buddoor, Katha... The very names of these films of the Eighties still bring a smile to our faces, films that were not exactly “arty” stuff but middle-of-the-road cinema that enveloped us with warmth, much like a quilt does.

Sai Paranjpye’s memoir is, like her films, straight from the heart, rich in anecdotes and facts that document a remarkable journey that began soon after she was born to Shakuntala Paranjpye, a Cambridge graduate who worked with the International Labour Organization in Geneva, returned to India and became a social worker and also a member of the Rajya Sabha, and Russian painter, Youra Sleptzoff, the son of a general in the Czar’s army who was killed in battle, forcing the family to flee the country during the Revolution and settle down in Switzerland.

Paranjpye produced her first literary work when she was eight, a set of fairy tales for children in Marathi called Mulancha Mewa (Treats for Children). She hasn’t stopped writing or telling stories since — scripting and directing plays, films, documentaries, and television serials for children and grown-ups alike over her decades-long career.

Paranjpye begins her book with her childhood and then proceeds to cover her life and career in meticulous detail. From the break-up of her mother’s marriage to her father, her stint at All India Radio, Poona, her tryst with drama at Children’s Theatre, her education at National School of Drama, her marriage to Arun Joglekar, a fellow theatre enthusiast, motherhood, a teaching assignment at Film and Television Institute of India, her eight-year stint at Doordarshan to her films and foray into television.

Every chapter is rewarding: a delightful anecdote here, a tug of the memory there. She laces incidents with wit. She is candid, but never harsh. And her self-deprecating humour comes through right from the first line of the book: “I was born different,” she writes, and goes on to say: “No matter where, I stood out. Stuck out like a sore thumb.” Her sharp memory not only allows Paranjpye to write on events that happened decades ago, but also retell them in a lively manner.

Her travels to France for example, where she won a scholarship to study theatre and television. Paranjpye’s descriptions are vivid and lucid and it’s clear that the trip was an important part of her life as it allowed her to meet her father, Papa as she called him, after 26 years in a town called Divonne-les-Bains, close to Geneva just across the Swiss border. Their bonding is a story of warmth lovingly told, as are her experiences with the extended Russian side of the family in Geneva.

From the memoirs, one gets a very clear idea about Paranjpye and her films, including the lesser known ones like Disha and Papeeha. She writes in painstaking detail as to how the movies were made, right from their conception to their being awarded. Sparsh, for example, had a troubled journey with Paranjpye struggling to find a producer and finally settling for Basu Bhattacharya, who was known for his tight-fisted approach to film-making. So exasperated was Paranjpye with Bhattacharya that she named the wily and unscrupulous character played by Farooq Shaikh in Katha Vasudev or Bashu Bhat!

She also dwells at length on the controversial Saaz, the only film, Paranjpye says, “I did not enjoy making”.

Across her memoir, Paranjpye shares many poignant memories, like the last days of the composer Kanu Roy, who gave the music for Sparsh, and how he blamed Bhattacharya for his precarious and penniless situation while on his deathbed.

The book is also replete with untold stories. How a documentary on the singer-composer Pankaj Mullick was made and how she even got the pioneering music director Raichand Boral — with whom Mullick’s relationship had, over time, soured to such an extent that they had stopped talking — to say a few complimentary words. She also mediated between Hemant Kumar and Mullick, who, too, had drifted apart and were totally estranged, and got Hemant Kumar to even sing for the documentary. Sadly the film was not preserved and cannot be traced in Doordarshan’s archives.

And of course, there are stories that will make this a treasure-trove for trivia-hunters. Like, for example, did you know:

- How a brainwave helped Sadhu Meher win the National Award for best actor for Ankur?

- How one of Paranjpye’s students of acting at FTII got picked by Raj Kapoor, but not as an actor?

- What does “Operation Pest Control” mean with regard to the FTII hostel?

- What was M.F. Husain’s daily wage rate when he painted images of actors on boards advertising films?

- How would the teleplays Raina Beeti Jaye and Dhuan Dhuan, both based on song names, get universal acclaim later?

- That a particular actress — and a famous one too — cut her foot on the glass shard in the makeup room during the inaugural programme of the Bombay TV centre in the early Seventies — but danced valiantly leaving footprints stained in blood on the stage?

Also making for insightful reading are the chapters on her stint as producer in a still nascent Doordarshan in the early Seventies. TV then wasn’t as male-dominated as other media and offered women with creative instincts like Paranjpye a platform to challenge set conventions. Paranjpye cites the example of a programme she created called Milady on Wheels. Not too many women in India drove cars those days and this show profiled those who did and their triumphs and tribulations.

A Patchwork Quilt is actually an English translation of Paranjpye’s Marathi language autobiography Saya. Paranjpye chose to translate it herself after expanding it and including several new chapters. The book not only showcases her excellent command over the medium of English narration, but it is also like a running commentary on the history of theatre and middle-of-the-road cinema in Bombay during the early 1980s.