Book: The Ottomans: Khans, Caesars, And Caliphs

Author: Marc David Baer

Publisher: Basic

Price: ₹799

Remember the Netflix series Dirilis: Ertugrul, whose massive popularity led many to dub it as a ‘Muslim Game of Thrones’? It was a show full of palace intrigue and valiant wars, hunky warriors and captivating women. Now, imagine if it was real. Impossible, you say?

Consider the anecdote about the “four-crowned golden helmet” that Suleiman I, better known as Suleiman the Magnificent, commissioned for himself to contest Charles V’s claim as the official descendant of the emperors of glorious Rome. He wore it on his imperial procession through the cities of Europe “on a horse richly adorned in jewels under a brocade canopy with flags embroidered in jewels”. Or the story about how the mentally unsound Mustafa I was removed from the throne by the machinations of the chief eunuch of his harem, Mustafa Agha, because in public the monarch would wildly gesticulate as if he was scattering golden coins among the populace. Truth, at times, can resemble fiction, the kind that made Dirilis: Ertugrul so popular.

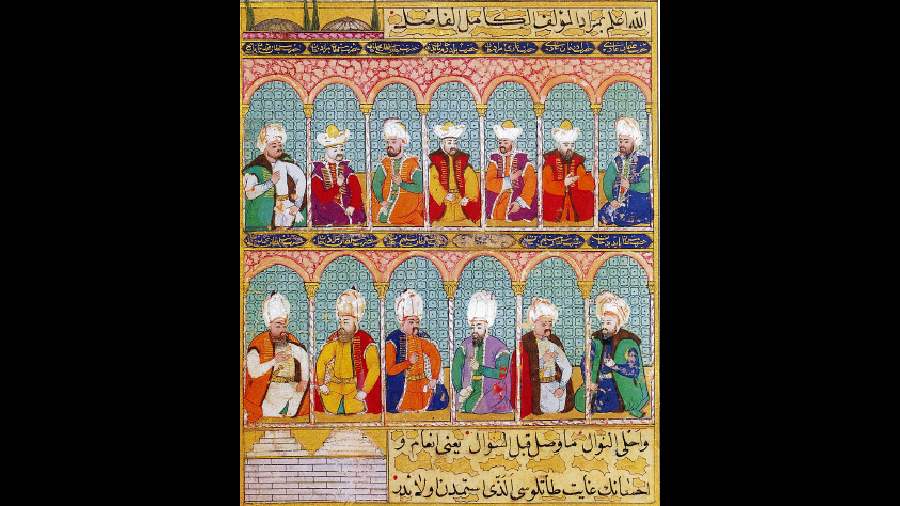

Marc David Baer’s account of the rise and fall of the Ottoman empire spans the entirety of its existence, right from the time of its establishment by Ertugrul’s son, Osman, as a vassal to the Mongols, to the reprehensible Armenian genocide prior to the First World War, and its ultimate abolition with the help of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk. Unlike history books which bore you with a dry elucidation of facts, The Ottomans is panoramic in its approach, taking constant detours to explain the influence that lesser-studied sects and personalities had on the progression of the dynasty. Deviant dervishes and the royal harem thus feature prominently in Baer’s account.

Baer also takes great pains to question the stereotypes constructed about the Muslim Orient by the Christian Occident. Traditional imagery of the Ottoman regents and their subjects being bloodthirsty, lustful aberrants — manifest in paintings like Eugene Delacroix’s The Massacre at Chios — is methodically deconstructed with accounts of the reconstruction of Constantinople by Mehmed II after he had conquered it along with examples of concubines rising to power, such as Hurrem Sultan who was married to Suleiman I “in a lavish spectacle complete with marching giraffes”.

However, the empire’s history is not viewed through rose-tinted glasses. The common practice of fratricide — after a king’s death, the heir would summarily execute all other claimants to the throne — is discussed at length. Religious intolerance is deliberated upon, with the murder and dismemberment of a Jewish lady-in-waiting, who had dared to accumulate personal wealth, described in gruesome detail.

The Ottomans is a wonderfully polished examination of one of the longest-reigning empires in human history. If your only experience of Ottoman history has been through books that are like the Age of Empires video games — buildings transforming, eras advancing instantaneously — then Baer’s book is one you shall greatly relish.