The distance between Nimati Ghat, near Jorhat in upper Assam, and Majuli island is about 29 kilometres. But to reach the world’s largest riverine island embedded in the mighty Brahmaputra river takes about one-and-ahalf hours. The huge launch MV Indra, choc-a-bloc with travellers, represents the microcosm of India — ethnic Assamese of all kinds of faiths, tourists from other Indian states and foreigners.

The elderly women and men with rasakali on their foreheads, tulsi malas around their necks, and prayer beads in their hands form a conspicuous group. Indeed, for most Vaishnavas, Majuli, the site of many satras or Vaishnav monasteries — some dating back to the 16th century — is a pilgrimage.

The launch is packed with cars, autorickshaws, motorcycles and cycles. Some passengers have brought along goats. An old rate chart by the ferry terminal reads: “Elephant with mahout, Rs 907.”

The shoreline of the island appears only after you’ve crossed miles and miles of water. And finally, the boat touches the shore. A 10-seater taxi, endearingly referred to as “magic gari” by all, negotiates metalled roads, dirt tracks, runs past paddy fields and lily pools.

After about a 10-kilometre journey, the gates of some temples and satras loom into view. These have been founded by Srimanta Shankara Deva (1449-1569 AD), the great Vaishnavite saint and social reformer, and his disciples. The saint abhorred idol worship and focussed on community prayer and simple rituals to bind together people of diverse origins in Assam and beyond. He used art and culture to spread his philosophy of monotheism which was further developed by his disciples.

Of the 64 satras, only 22 survive. Repeated flooding of the Brahmaputra and its tributaries, year upon year, has devoured the rest.

To attract various tribes and people following animistic traditions, apart from simple naam gaan (prayer songs), the saint scripted ankiya bhaonas (one-act plays) and classic literature. His influence on the socio-cultural life of the people of Assam and beyond is part of the Bhakti movement in medieval India. He challenged caste hierarchy, emphasised the individual’s direct connection with God and provided the impetus to end the hegemony of Sanskrit over regional languages.

Although naam gaan remains the primary method of invocation to this day, outside the sanctum sanctorum, most satras are now adorned with multiple idols of Vishnu and his avatars.

Out of the 22 satras, there are four that follow a unique tradition of mask-making; two satras at Samaguri are most frequently visited by tourists and researchers.

The intricately created masks are used in opera-style plays depicting mythological tales of good triumphing over evil, namely, Krishna vanquishing Kaliya, Putana, Bakasura and Kamsa, or Rama trumping Kumbhakarna, Maricha and Ravana. A unique feature of these demonic masks is that they are not always terrifying depictions. For instance, in the masks and also the bhaonas, Ravana is not portrayed as a villain, but as a great warrior and a devotee of Shiva.

Natun Samaguri is a vibrant satra. That day, the mask-maker there, Pradip Goswami, is putting the finishing touches to the mask of Garuda, the mythical bird who is Vishnu’s mount and famed enemy of all snakes. Garuda’s face is a bright yellow and its beak flaming red. Goswami explains the process of mask-making. He says, “We cover the bamboo frame with cotton cloth, slather on potter’s clay and cow dung. The structure is dried in the sun for a couple of days before we start to paint it.”

Inside a huge hall of the satra, there is a collection of masks, about a hundred of them, all hanging from the walls.

Dhiren, Pradip’s elder brother, launches into an explanation of what is what. “We call masks mukha and there are primarily three types. Mukh mukha, which is worn over the face, Cho mukha, which covers the entire face, and Lotokai mukha is a combination of artificial body parts used by the actors in the bhaonas.”

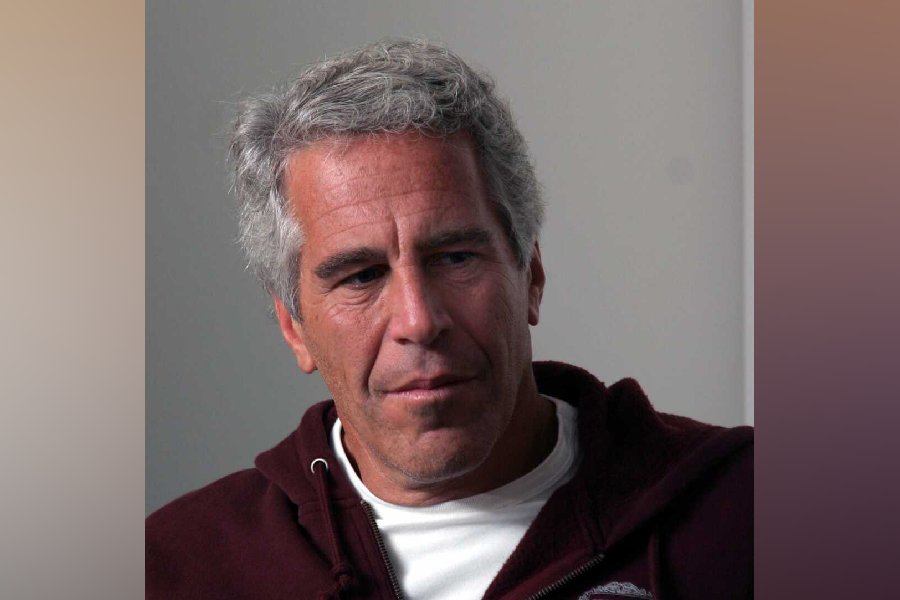

Pradip Goswami and others make masks at Natun Samaguri Satra Prasun Chaudhuri

Pradip and Dhiren’s father was the late Koshkanto Dev Goswami. He was the satradhikar or head of the satra. Koshkanto not only created marvellous masks, he was also a good actor. He even got the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award. The Goswami brothers’ elder cousin Hem Chandra, yet another craftsman and artist, was given the Padma Shri for keeping alive the tradition of mask-making. Hem Chandra has been training young people from different parts of the world in the craft. Students groomed at his training institute, the Sukumar Kala Kendra, travel across India and abroad and perform bhaonas.

Masks created at Natun Samaguri Satra are preserved in various museums in India and abroad, including the British Museum. Arifur Zaman, an associate professor of anthropology at Gauhati University, says, “T. Richard Blurton, curator emeritus of the British Museum, visited Majuli in 2015. He visited Natun Samaguri Satra to learn more about the masks here. In 2016, he curated an exhibition at the British Museum titled Krishna in the Garden of Assam.” Zaman has studied the phenomenon of mask-making and the tradition of bhaonas at the satras for over a decade. He has written a book titled Tradition of Mask Making in Vaishnavite Monasteries of Assam. He says, “These masks are anthropologically and culturally unique. They represent a distinctive form of cultural renaissance in which people from various castes, creeds and religions in the Northeast were united by Srimanta Shankara Deva, one of the greatest social reformers of India.”